Pietro Longhi is a wonderful Venetian eighteenth century painter who, unlike some of his contemporaries in Venice, devoted himself to portraying the simple beauties of everyday life. These days I enjoy gazing at his genre scenes and let’s take a look at a few interesting ones.

Pietro Longhi, The Painter in His Studio, 1741, oil on canvas, 41 × 53.3 cm (16 1/8 × 21 in)

Pietro Longhi, The Painter in His Studio, 1741, oil on canvas, 41 × 53.3 cm (16 1/8 × 21 in)

A painting is a finished work, but in Longhi’s painting “The Painter in His Studio” we see the hidden, mysterious aspect of art and portrait painting; we see what happens behind the curtains, a sweet secret that only the artist, the sitter or the model know. In this work, a painter is painting an oval portrait of a Venetian noblewoman. Her clothes speak of her wealth and importance. I deserve to be captured for eternity on canvas, her gaze seems to say. Her hair is powdered and short, her stays laced, and a little dog is peeking under her lace sleeve. Considering how wide her sumptuous dress is, perhaps there is another dog hiding in there. Their carnivals and their masques, one never knows with these Venetians, what are they hiding, what is real and what a mirage. The man beside her; is he her husband, her brother, a father or a friend, we don’t know. But he also has a Venetian masque on his face, moved to the side though. Maybe he is telling the painter something really important. And look, his hand is about to pull something out of his inner pocket, what is it, a dagger? In case he is displeased with the painter’s work. Or some gold coins, if he thinks the likeness of the two faces, the one on canvas and the one in reality, is astounding. On the left of the painter, we see his painting equipment. The background is painted in muted brownish tones and is empty of details and ornamentation, we don’t see the continuation of rooms or space, which makes these three characters seem like actors on the stage, but then again, aren’t we all?

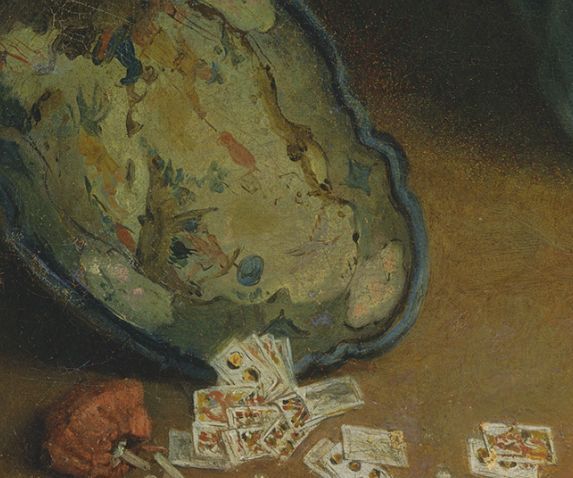

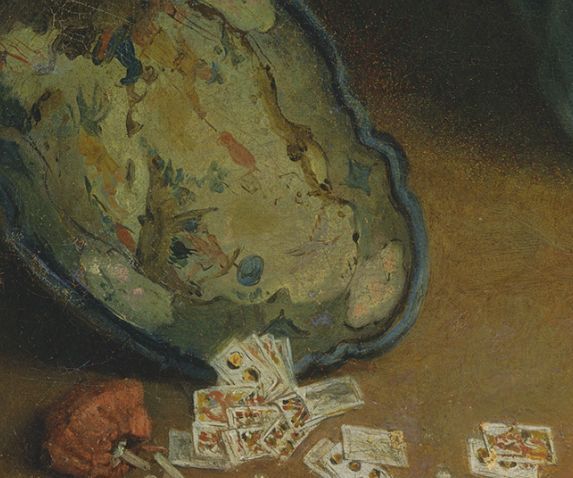

Pietro Longhi, Fainting, 1744, 50×61.8 cm (19 11/16 × 24 5/16 in)

From a calmness of a portrait sitting painting we are moving on to a more dramatic scene, painted around the same time, 1744, when Longhi was about forty-two years old; it is unsure whether he was born in 1701 or 1702. A lady dressed in a pastel pink gown, deadly pale and weak, is just opening her eyes. Quick, quick, someone call the doctor! The lady had fainted. Oh, she is opening her eyes slowly now. Her one hand is on her breast, the other is hanging limp. A soft pillow was brought so she can lay her head on it, and smelling salts are offered to her delicate nostrils. Do not let this pastel pink sweetness fool you, for this scene is not as innocent as it may seems at first.

The evidence of the crime lays open to our eyes in the bottom left corner; an overthrown little table with a notably Rococo playful and flamboyant chinoserie pattern, cards and a little velvet purse full of coins are scattered on the floor. People have gathered sympathetically around her, but this lady has a card or two up her sleeve. The reason she fainted is not the lack of fresh air, or the stays laced too tight, but rather the fact that she was loosing in the game. What else can she do but stage this silly little incident. Ha, but the man dressed in a long blue cloak and a long dark grey wig on the right doesn’t seem to believe her. His hand is stretched towards her as if he’s asking for the money. Italian playwright Carlo Goldoni praised Longhi’s portrayal of truth on his canvases, portrayal of the real world around them, and the painting “Fainting” most likely inspired Goldoni’s comedy “La finta ammalata“ or “The Fake Patient Woman” (1750–1751); there’s a scene in which the main character Rosaura had just fainted and she is surrounded by her friend, her suitor, her father and her doctor.

Pietro Longhi, The Game of the Cooking Pot, 1744, 49.8 × 61.8 cm (19 5/8 × 24 5/16 in)

Another charming and slightly confusing scene is presented in the painting “The Game of the Cooking Pot”. The lady in the gorgeous white gown is a sight to behold; her delicate pale face, her tiny pearl earring, a subtle pink flower in her powdered hair, her little white shoe peeking under the dress, all so dainty and doll-like in the typical Rococo way. But then there’s a guy on the right, holding a stick, his eyes tied with a handkerchief so he cannot see, and he is about to hit … the pot? The Game of pentola or The Game of the Pot is yet another one of strange Rococo games played by adults and not children which includes a person who has to strike the pot and smash it in order to find a pleasant surprise underneath. In a fancy Rococo interior carefree and pretty young people are indulging in lighthearted fun, and why would they not? Life is to be enjoyed. In the background, on the left, there’s some wine in jugs and some biscuits, little details that Longhi painted to add his scenes some warmth and domesticity.

What were the Venetians up to in the 1740s. This is sort of like an Instagram of their day and age; everything is smooth and perfect, there’s no smallpox, pimples, sadness or a bad hair day. Everyone is “caught” on the canvas having so much fun, like in a group selfie, a big smile everyone! And of course they are having much more fun than you are. Pietro Longhi’s focus on painting genre scenes led the art critics to compare his work to that of his English contemporary, the famous brutally satiric William Hogarth. This comparison isn’t true at all. They both placed their focus on the everyday life on their age and area, but Hogarth’s work tends to be harsh, his wittiness turns to sarcasm, whereas Longhi’s world is delicate and dainty, and figures in his paintings look like actors on stage, their face expressions and movements carefully devised to tell the tale. Pastel colours, fine brushstrokes, Longhi shows both the refined and frivolous past times of Venetians around him; gambling, playing games, sitting for portraits, reading letters, dancing, taking music lessons, receiving visitors. Every canvas is a scene from life. Also, the notable small size of these interior scenes is another thing which connects Longhi’s art with that of Vermeer and other seventeenth century Dutch painters who portrayed daily life, though with more modesty, mystery and coldness, they are after all people from the dark, rainy, and gloomy North.

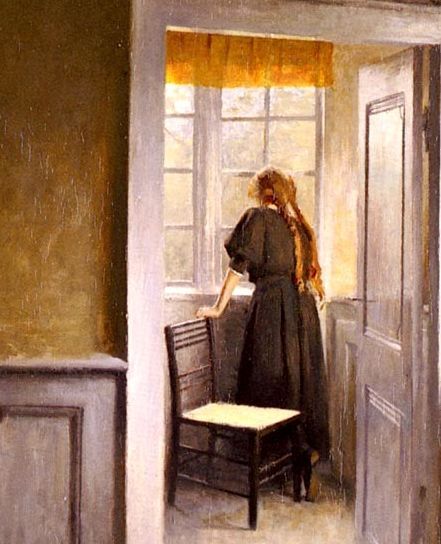

Pietro Longhi, The Letter, 1746, oil on canvas, 61 x 49.5 cm (24 x 19 1/2 in)

In this painting I love the detail or a washing line with the white garments painted in such loose, feathery soft, almost ghostly strokes, it just looks so delicate, and adds to the aura of gentleness which matches the pale pretty girl’s pastel pink gown and a sweet round face.

Pietro Longhi, The Music Lesson, 1760, oil on copper, 44.6 x 57.6 x 0.2 cm (17 9/16 x 22 11/16 in)

Since when is holding hands crucial for learning the notes? Hmmm…. The music teacher’s profile alone, with the wide wicked smile and those eyebrows indicates a lecherous Faun-like nature. And look at the way the little dog is observing it all, with his paw in the air.

Tags: 1741, 1744, 1746, 1760, 18th century, 18th century art, art, Carlo Goldoni, charming, comedy, Everyday life, Fainting, genre scene, Hogarth, interior, interior scene, Italy, La finta ammalata, Longhi, Pietro Longhi, playwrighter, portrait, Rococo, The Fake Patient Woman, The Game of the Cooking Pot, The Letter, The Music Lesson, The Painter in His Studio, Venetian painter, Venice, Vermeer

Edgar Degas, Rest, 1893, pastel

Edgar Degas, Rest, 1893, pastel