“Sad veiled bride, please be happy

Handsome groom, give her room

Loud, loutish lover, treat her kindly

(Though she needs you

More than she loves you)…”

(The Smiths, I know it’s over)

Vasily Vladimirovich Pukirev, The Unequal Marriage, 1862, oil on canvas, 173 x 136,5 cm

Vasily Vladimirovich Pukirev, The Unequal Marriage, 1862, oil on canvas, 173 x 136,5 cm

Pukirev, the son of a peasant who had originally been trained to be an icon painter swept the art scene when he presented his very large canvas “The Unequal Marriage” in 1863. Pukirev had just finished studying at the School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture in Moscow and this painting was an ambitious and successful attempt to portray a scene from an everyday life (well, a wedding may not be an everyday thing, but it’s not a theme from history or religion) in a serious, not sentimental manner. The scene looks like a very dramatic moment in a play; the light in the church is falling on the three main figures in the painting; the bride, illuminating her beautiful and sad figure of the bride, the wrinkled and dull looking old groom, and the hunched priest. The bride and the groom are both holding a lighted candle. The bride; beautiful, shy, and melancholy, is the picture of innocence. Her lovely pale oval face is framed with silky curls that touch her collar bones and her necklace. Jewels glimmers on her skin, blossoms on her wreath are blooming, but her heart is a poor withered flower, sad and cold. The crinoline is heavy on her slender frame, and her downward gaze reveals more than it hides. We cannot see the look in her eyes, but we can feel what she is feeling, we can imagine the soft tears blurring her visions, we can imagine the dryness in her throat when the moment to say “I do” comes.

The idea for the painting came from this one particular real life story; Pukirev’s friend Serge Mikhailovich Varentsov, a young merchant, was hopelessly in love with a twenty-four year old girl Sofya Nikolaevna Rybnikova, but her parents decided it would be better for her to marry a man who was richer and more succesful, a thirty-seven year old Andre Aleksandrovish Karzinkin. The age different wasn’t as big as the painting presents it, but Pukirev wanted to emphasise the bride’s youth and beauty in contrast to the man’s old age and fading looks, so the artistic freedom is understandable and justifiable. Poor, lovelorn Sergei was nonetheless forced to attend the wedding and see his beloved marry someone else, due to family reasons; his brother Nikolai was married to Karzinkin’s younger sister. One man’s sadness was another man’s inspiration and when Sergei told this to his friend the artist, Pukirev instantly had the idea of a painting in mind. The man behind the bride is suppose to be portrait of Sergei but later Sergei was rather angry that Pukirev had painted him and so Pukirev added a beard to the face but the rest remained unchanged. Still, the artist’s friend S. I. Gribkov said for the bearded man that: “with crossed arms in the picture, it is V. V. Pukirev himself, as if alive”. The theme of the painting and the social problem it accentuates reminds me of something from Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment”; the main character Raskolnikov’s intelligent and beautiful sister Dunya takes upon herself to better the family’s financial situation by marrying an old and wealthy, but not good-hearted lawyer Luzhkin. In the end, she doesn’t proceed and she ends up marrying Raskolnikov’s best friend Razumikhin who is intelligent and strong and, unlike Luzhkin, he loves her dearly.

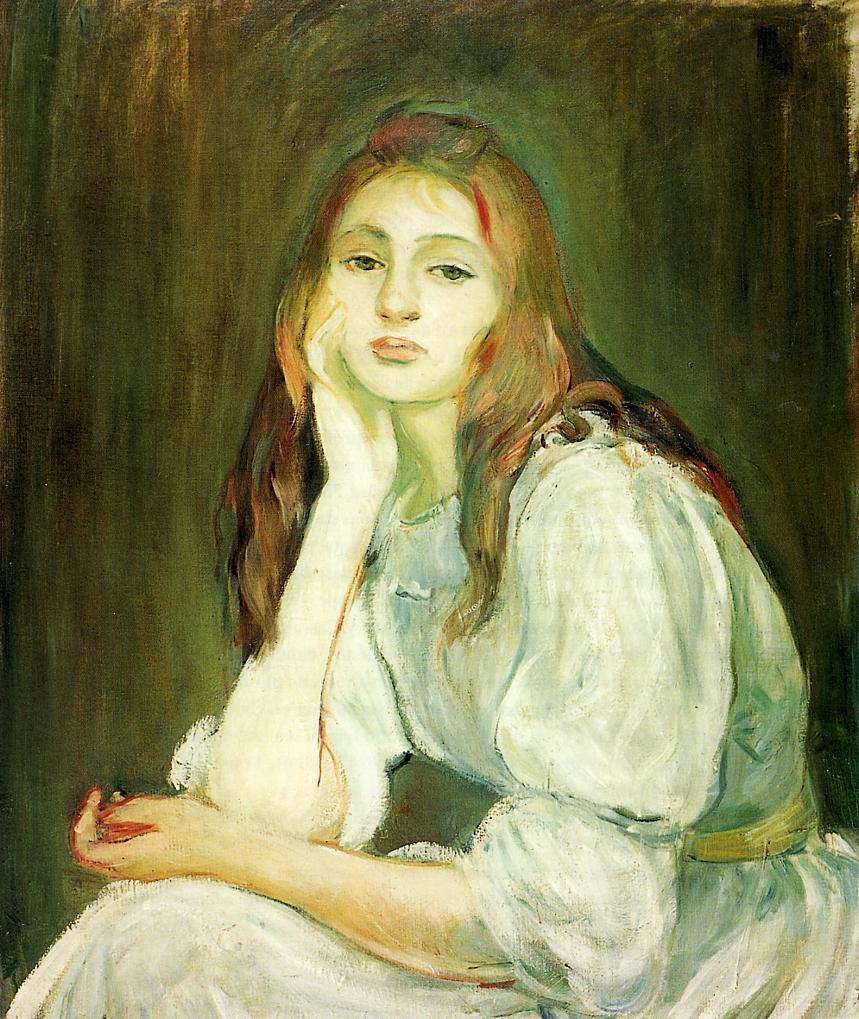

First Zhuravlev, After the Wedding, 1880

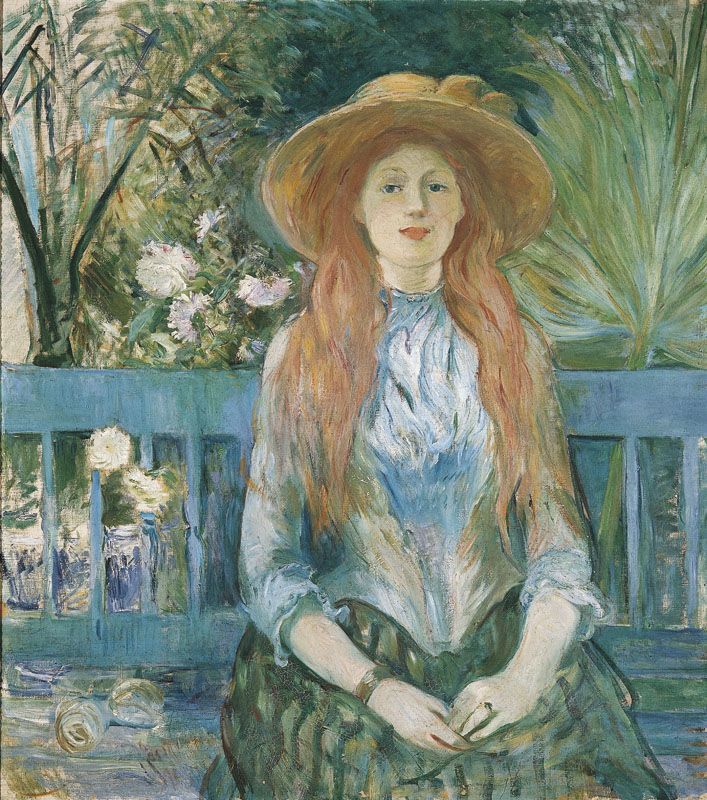

Auguste Toulmouche, The Reluctant Bride, 1866

More sad brides!

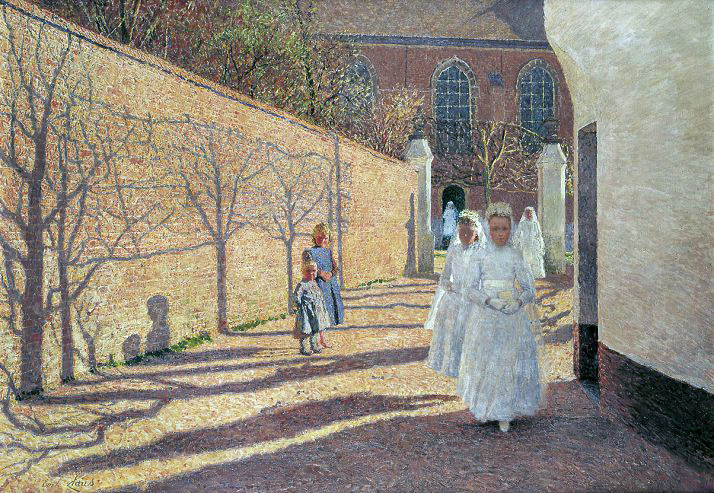

Jules Bastien-Lepage, First Communion, 1875

Jules Bastien-Lepage, First Communion, 1875