Friendship of Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, who were both remembered for being a thorn in the eye of the art scene in the late Art Nouveau and early Expressionism phase of Vienna, was merely an artistic one. They both soaked each others ideas and for a very short time created from the same wellspring of inspiration, only to move apart and drift into totally different directions.

Egon Schiele, Mädchen mit übereinandergeschlagenen Beinen (Girl with crossed legs), 1911

Egon Schiele, Mädchen mit übereinandergeschlagenen Beinen (Girl with crossed legs), 1911

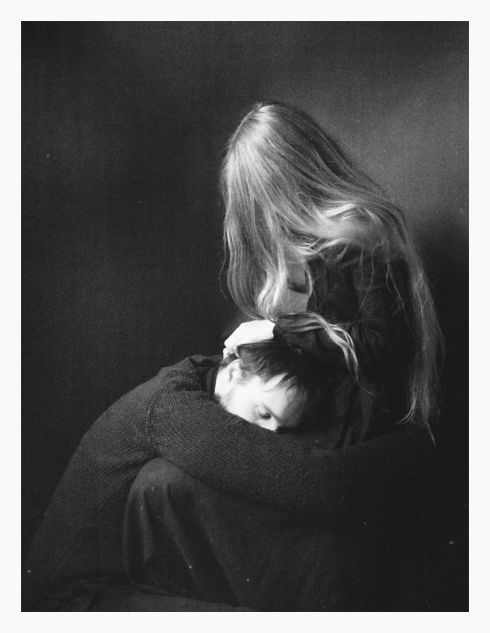

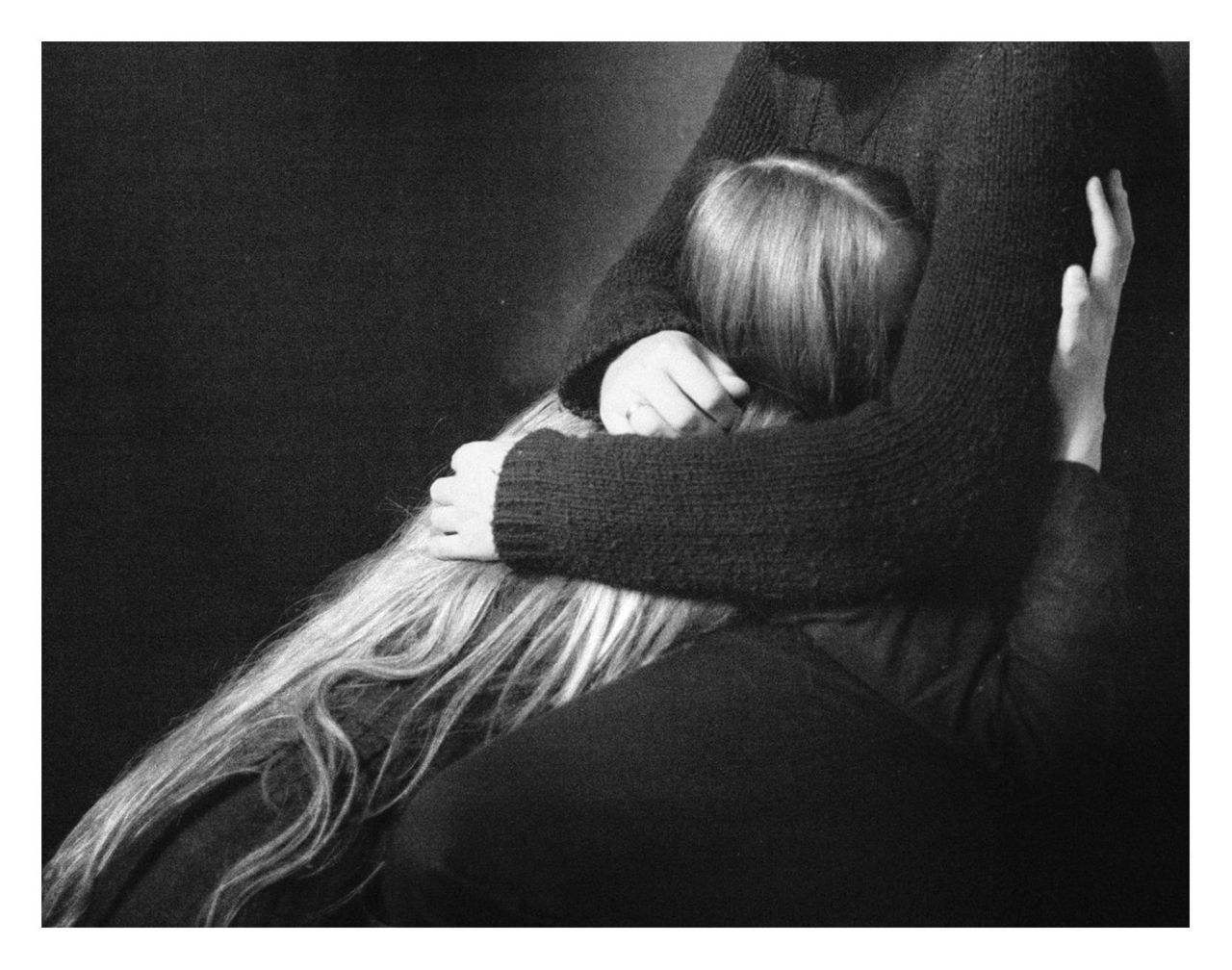

The very first thing you notice when gazing at Schiele’s portraits and nudes is their ‘elegantly wasted’ appeal mixed with some kind of twisted eroticism, smouldering melancholy and trashy glamour. There’s some subtle poetry of sadness about their worn out faces, tired eyes, sunken cheekbones, and their pale greyish skin. Completely nude, or dressed in lingerie and stockings, they gaze nervously, tiredly, forlornly at us; they provoke a response. Certain malaise pervades their smiles.

A true-blooded Expressionist, Oskar Kokoschka was the first to show interest in portraying the underprivileged, the poor, the misfits, but Egon Schiele soon followed his path, and they both worked and soaked inspiration in the gritty everyday reality of working class Vienna. Schiele’s drawings from 1910 and 1911 show resemblance to Kokoshka’s drawings from 1908 and 1909, but they are more poetical. In my view, Kokoshka’s drawings cannot even be compared to the power of his later paintings which are full of Expressionist frenzy, unsettling and distorted, painted in layers and layers of colour, as if every brushstroke brings relief. Below, you’ll see one of his drawing from this period which shows a half-nude girl. It slightly reminds me of Paul Gauguin’s way of portraying bodies, her face contour is strong, her body is kind of geometrical, overall she looks rough, stiff. This just shows that Schiele’s main method of expression was line, while in Kokoschka’s paintings colour plays a more important role. Kokoschka later even accused Schiele of ‘stealing’ his style.

Oskar Kokoschka, The juggler’s daughter, 1908, pencil, watercolour

But Schiele… Schiele’s drawings are like existentialist poems. He was an excellent draughtsman. Otto Benesh, son of Schiele’s patron Heinrich Benesh, wrote this of Schiele’s drawing technique: “Schiele drew quickly. The pencil skated over the white surface of the paper as though led by some ghostly hand… and he sometimes held the pencil in the manner of a painter from the Far East.” It’s also interesting to note that he never used an eraser; he rarely made mistakes, but when he did, he’d simply throw the paper away. And he sketched quickly, and then later, in the absence of the model, he’d fill in his drawings with watercolour or gouache.

Egon Schiele, Seated Girl Facing Front 1911

Egon Schiele, Seated Girl Facing Front 1911

The beauty of his drawings is unsurpassed, even Klimt once admitted to him that he is better at drawing. His lines seem fragile and constricted, but their firm and controlled nature cannot be denied. Schiele employed the language of melancholy and lyricism, in a similar way to Modigliani, and used it to portray his own bewildering loneliness. In my view, all of his portraits, nudes, sunflowers and landscapes, express the same thing – melancholy, death, decay, they are windows into his soul and mind. This is just what Caspar David Friedrich said: “The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees in himself. If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also refrain from painting what he sees before him.” Schiele always paints what is within him.

When he chose to paint these poor girls from the streets, he did so because he saw through their sunken cheeks and sad eyes, his artistic vision penetrated through their souls. Kokoshka is interested only in their bodies, but Schiele wants to see the world through their eyes. Kokoschka was interested in their crooked postures and inelegance because it suited his distorted visions of the world, whereas in Schiele’s drawings you see the souls behind their tired little bodies. Pale, skinny, beaten and hungry, unnoticed till that moment, these street urchins, mostly girls, always ignored, pushed into the corner, out of the way, were brought into the spotlight all of a sudden, which undoubtedly made them feel special, privileged. Someone noticed them, someone was nice towards them, someone wanted to paint them!

Egon Schiele, Girl with black hair, 1910

Egon Schiele, Girl with black hair, 1910

A sentence which sums it all, and which inspired me to write this post in the first place:

“Physically immature, thin, wide-eyed, full-mouthed, innocent and lascivious at the same time, these Lolitas from the proletarian districts of Vienna arouse the kind of thoughts best not admitted before a judge and jury.” (Egon Schiele, by Frank Whitford)

You’ll notice how awkward they look. Girl with black hair has a look of sadness and resignation in her eyes. For a while that has been one of my favourite of Schiele’s nudes because of the discord between her cute round face with large eyes and full lips, and the awkward skinny body with skin stretched taunt over the bones, and small breasts. She looks uncomfortable with being naked, she looks shy and hopelessly sad. My more recent favourite is the one below, Sitting girl with ponytail, again, I love her body and her skin tone, which Schiele obviously enjoyed painting. His nudes always look pale and sickly, but sometimes their skin has a greyish tone and sometimes it takes yellowish shades, but you’ll notice how he paints patches of unnatural shades of colour where they should not naturally be, like adding a bit of green, blue or brown on their bodies. And look at the face of this little proletarian Lolita – it resembles that of a sad and dreamy porcelain doll, eyes gazing in the distance, lips painted in rich red colour.

This is what Schiele’s friend Gütersloh wrote of these child models:

“There were always two or three small of large girls sitting about in his studio, brought there from the immediate neighbourhood, from off the street or picked up in the Schonbrunn park that was nearby. They were ugly and pretty, washed and unwashed and they did nothing – at least to the layman they might have seemed to do nothing… They slept, recovered from beatings administered by parents, lazily lounged about – something they were not allowed to do at home – combed their hair, pulled their dresses up or down, did or undid their shoes… like animals in a cage which suits them, they were left to their own devices, or at any rate believed themselves to be. (…) With the aid of little money and much charm he had managed to lull these little beasts into a false sense of security… They feared nothing from the sheet of paper which lay by Schiele on the divan.”

Egon Schiele, Sitting girl with ponytail (Sitzendes Mädchen mit Pferdeschwanz), 1910

Egon Schiele, Sitting girl with ponytail (Sitzendes Mädchen mit Pferdeschwanz), 1910

I think Schiele’s pencil and brush could have captured the appearance of Sonia Marmeladova from Crime and Punishment to utter perfection. Sonia is a pale, skinny, meek, painfully shy but deeply religious eighteen year old girl, and a prostitute who somehow manages to transcend the misery of her surroundings and remain pure at heart. And she also falls in love with Raskolnikov. Don’t they make a splendid match: a killer and a harlot. This is how Dostoevsky describes Sonia in the book:

“She had a thin, very thin, pale face, rather irregular and angular, with a sharp little nose and chin. She could not have been called pretty, but her blue eyes were so clear, and when they lighted up, there was such a kindliness and simplicity in her expression that one could not help being attracted. Her face, and her whole figure indeed, had another peculiar characteristic. In spite of her eighteen years, she looked almost a little girl- almost a child.”

Sonia is one of my favourite literary heroines, and ever since I’ve read the book, I wondered what she looked like. Now I know that only Schiele could capture that irregular pale face, that fragile thin body, those big bright eyes. No doubt he would be attracted by her childlike figure, but would she dare to pose for him, as shy as she was? I don’t know, but maybe modelling would be better than prostitution. There’s a lot of descriptions of poverty in the book as well. Sonia’s little brothers and sisters, and her step-mother Katerina live in bad conditions; each has only one clothing garment, which Katerina washes every night, they are always hungry and frail, often ill. We can assume that the working class Vienna of Schiele’s time was no different, and that all these little innocent creatures that Schiele has painted with such zest probably lived similar lives. It was all very poignant to me. You just can’t read a book by Dostoevsky, close it, and not come out changed.

Oskar Kokoschka, Children Playing, 1909

As you can see by now, I can’t get Egon Schiele out of my mind. He is one of my favourite artists, and the more I read about his art, the more richness I discover. These days, I think, read, daydream about his art, various aspects of it, a lot, and I can tell you one thing – there are so many interesting fragments about his art that even a hundred posts wouldn’t be enough to explore his magic. And he has indeed woven magic over me.

Tags: art, Austrian art, Austrian artist, children, Crime and Punishment, Death, decadent, decay, Egon Schiele, Expressionism, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, heroin chic, Literature, Lolita, melacholy, Nudes, Oskar Kokoschka, Painting, poverty, proleterian, Sadness, skinny body, Sonia Marmeladova, Vienna, working class

Vasily Vladimirovich Pukirev, The Unequal Marriage, 1862, oil on canvas, 173 x 136,5 cm

Vasily Vladimirovich Pukirev, The Unequal Marriage, 1862, oil on canvas, 173 x 136,5 cm