In lyrics Syd Barrett wrote for Pink Floyd and his two solo albums, he crated a tapestry of images, moods, fragrances and colours that change from vibrancy and childlike whimsicality of early psychedelia to more sombre, tinged with melancholy tunes that smell of withered flowers, last summer sunsets and have that after party mood when the guests are gone, the music stops and solitude remains. In many of his songs, images from nature serve to mirror the state of his soul, his emotions and his loneliness.

“Jiving on down to the beach to see the blue and the gray

Seems to be all and it’s rosy-it’s a beautiful day!”

(Gigolo Aunt)

John William Waterhouse, Ophelia, 1894, detail

John William Waterhouse, Ophelia, 1894, detail

Syd Barrett was the imaginative and stylish individual behind the early Pink Floyd. He also went on to have a brief solo career and released two albums in 1970; “The Madcap Laughs” and “Barrett” which mostly feature his melancholy voice and guitar, mirroring the dark and sad waters of his soul. Although the mood of Syd’s lyrics changes from the early ones which are fun and quirky, and later ones which tend to be more mystical and introspective, there is a theme which lingers throughout Syd’s poetry – nature.

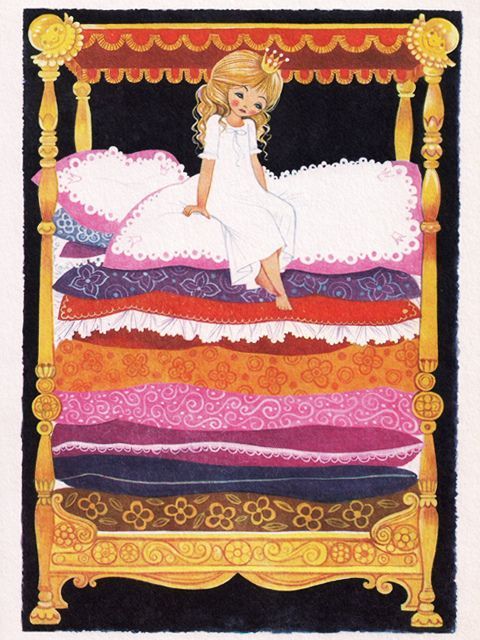

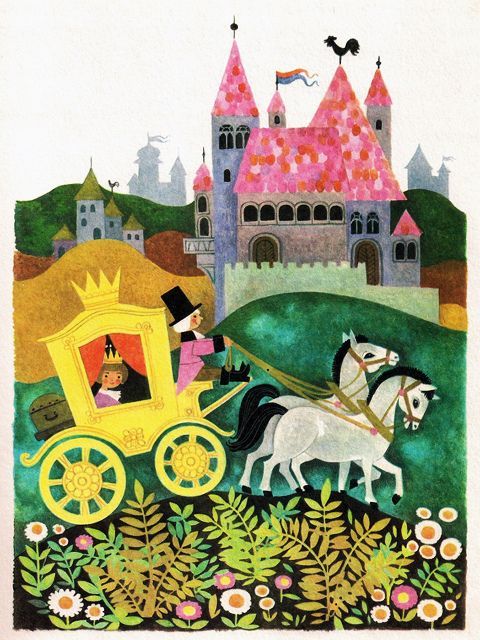

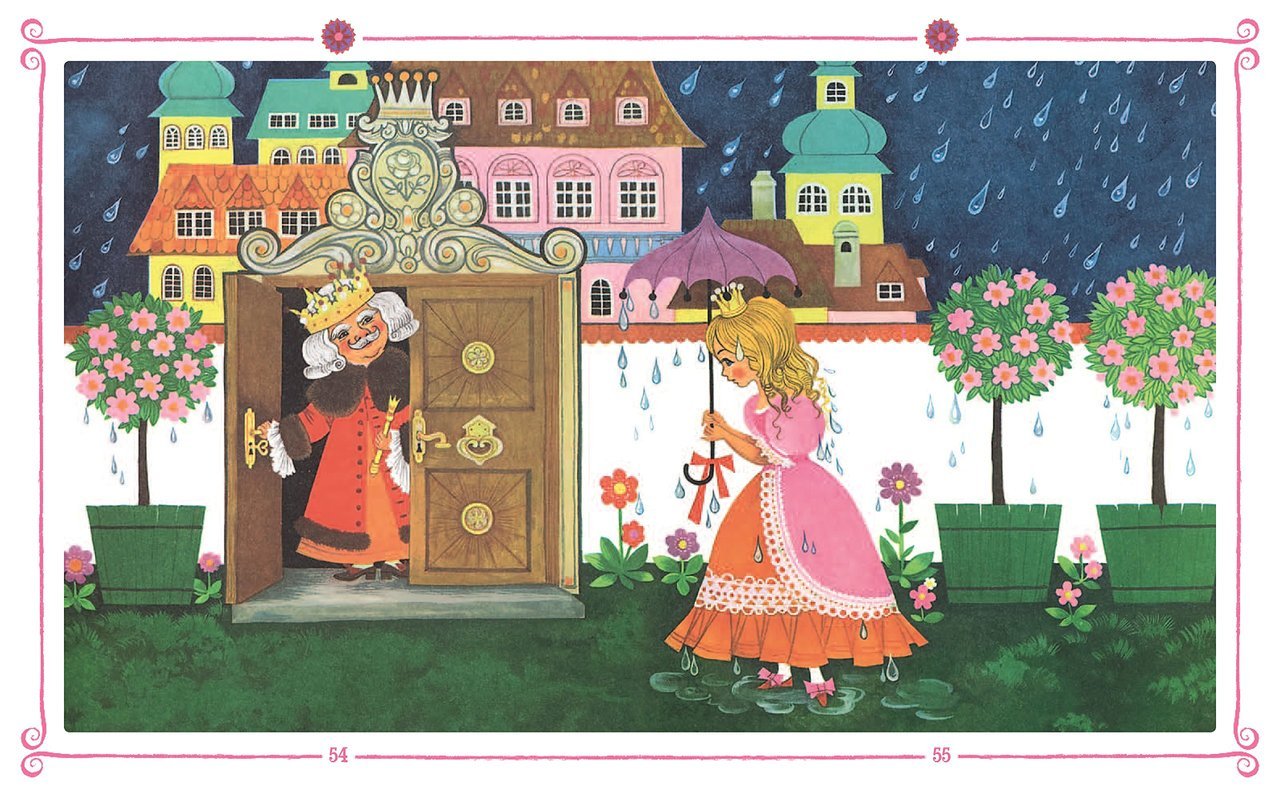

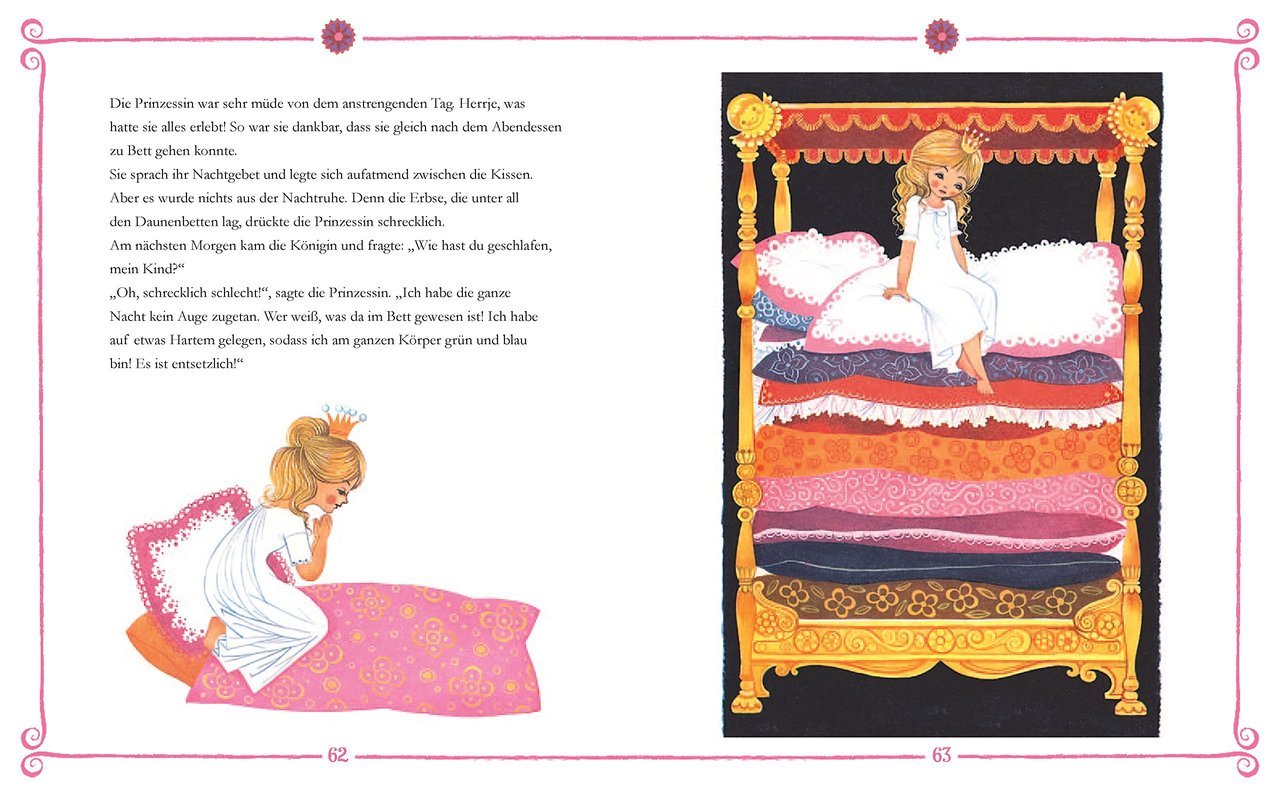

The reason behind the frequency of nature as a topic of Syd’s lyrics is tied to his childhood; where he grew up and how he grew up. Syd was part of the baby boom generation and grew up in a safe and clean middle-class neighbourhood in Cambridge where his father worked as a pathologist. Unlike Morrissey, for example, whose early memories are tied to the dark and grim streets of Manchester and a red brick house which he can never go back to, the stage of Syd’s early memories is a lovely Victorian house where mum read fairy-tales and the arts were appreciated. Despite being only an hour away from London, Cambridge was, at the time, still a quaint town where myths and reality lived in harmony.

Constant Puyo, 1903.

Constant Puyo, 1903.

In the book “Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd: Dark Globe”, the author Julian Palacious describes the area as a”bleak land rife with myth; a land where one can see the ruins of monasteries and abbeys looming through the heavy autumn fog, the spring of the Nine Wells associated with druids and witchcraft, a place where cold winters bloom into chill and damp springs and violet flowers fill the meadow all the way to the Beechwoods, a place of fairy ring mushrooms and willow trees gently touching the surface of the river Cam with their long yellow branches; all in all a setting ideal for a psychedelic schoolgirl to explore the secrets that nature beholds and float down the river forever and ever like a modern Ophelia: Syd conjured the very thing in his song “See Emily Play”. Palacios further says that “The Fens were rumoured to be the haunt of lost souls, witches, and web-footed peasants”, thus mingling the vivid Celtic past and mystic of nature with everyday suburban reality.

Arthur Rackham illustration for The Old Woman in the Wood from The Grimm’s Fairy Tales

In his book “Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head”, Rob Chapman also comments on nature being a common theme in Syd’s lyrics “Like Lear, Syd would populate his lyrics with imagery drawn from botany , zoology and nature. Lear and Caroll influenced the clarity of his lyrics too…”, adding that Syd “grew up surrounded by Fen countryside, absorbed in pastoral pursuits and Arcadian literature, and frequently drew upon nature for the subject matter of his artwork. His father was a keen amateur botanist and the entire family were be taken for Sunday morning jaunts to the Cambridge Botanical Gardens. The experience would be ingrained and absorbed from an early age.” We might say that nature was Syd’s first love, one which came before painting and music, and one which stayed much longer, even in his old age when he tended to the roses in his garden.

Photo found here.

In his early writings for Pink Floyd, nature is the setting of Syd’s psychedelic imaginings. In one song from their first album, “Flaming”, a very cheerful tune, nature comes alive and the meadow is one big playground. The lyrics bring to mind whimsicality of Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland: “Alone in the clouds all blue/ Lying on an eiderdown/ (…) Lazing in the foggy dew/ Sitting on a unicorn./ No fair, you can’t hear me/ But I can you./ Watching buttercups cup the light/ Sleeping on a dandelion.” Through his perceptions of nature, Syd paints us the landscapes of his soul, through the sounds we see its changing colours from yellow, gentle green and pink, to greys, dusty pinks and faded blues.

The first hint of the darkness to come can be traced in the lyrics of “The Scarecrow” where a solitary scarecrow standing in the middle of a golden barley fields brings to mind the sad landscapes that Vincent van Gogh had painted near the end of his life. Another song, “Octopus” from his first solo album, mingles the cheerfulness of his early days with a premonition of the madness that was to come: “Isn’t it good to be lost in the wood/ Isn’t it bad so quiet there, in the wood/ Meant even less to me than I thought… the seas will reach and always seep/ So high you go, so low you creep/ the wind it blows in tropical heat”. One time Syd was on holiday with his family in Wales, he was but a little boy, and he wandered off into the forest and was lost for hours.

“The land in silence stands” (Swan Lee)

And the landscape turns melancholy; the gates of childhood are closed, dandelions have withered and unicorns are nowhere to be found… the dark sea of adulthood is sad and mute as the grave, and its shore desolate and unpromising. Lost hopes and lamentation at the sudden awakening. There isn’t a song which better paints a picture of Syd’s mind at the time than “Wined and Dined” whose lyrics and melody both recall happier times and lament at the sadness that just doesn’t go away:

“Only last summer, it’s not so long ago

Just last summer, now musk winds blow…”

Melodies and lyrics of Syd’s solo albums bring to mind not the pictures of meadows and flowers, but scenes of isolation; murky waters, birds flying away, broken pier, trees are silent and lonely… Syd shows an acute awareness of what is going on around him. As a lyricist, and a poet too, Syd used images of nature as symbols for his states of mind and ways of expressing feelings imaginatively and indirectly; he is painting landscapes with his words which mirror the states of his soul.

Caspar David Friedrich, Moonrise Over the Sea, 1822

Here are some interesting lines from his song “She took a long cold look” from “The Madcap Laughs”, the image of the broker pier, wavy sea and water streaming over him are striking:

“a broken pier on the wavy sea

she wonders why for all she wants to see…

But I got up and I stomped around

and hid the piece where the trees touch the ground…

And looking high up into the sky

I breathe as the water streams over me…”

Picture found here.

A beautiful song “Opel” has long sad solos and a sense of isolation lingers throughout it, especially haunting are the last lines “I’m trying to find you” sang in his distant voice and accompanied by his guitar:

“On a distant shore, miles from land

Stands the ebony totem in ebony sand

A dream in a mist of grey…

On a far distant shore…

The pebble that stood alone

And driftwood lies half buried

Warm shallow waters sweep shells

So the cockles shine…

I’m trying

I’m trying to find you!

To find you

I’m living, I’m giving,

To find you, To find you…”

Tags: 1960s, Birthday, Cambridge, dreams, English countryside, Fairies, Games for May, London, lyrics, magic, Nature, nature in lyrics, Poem, Poetry, Psychedelia, Rock Music, Swinging London, Syd Barrett