Sargent’s Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose is one exceedingly beautiful, vivacious and dreamy painting set in a resplendent garden covered with a flimsy veil of purple dusk in late summer, August perhaps, when nature is at its most vulnerable and autumn creeps in bringing chill evenings and morning mists, and starts adorning the landscape with a melancholic beauty. Two little girls dressed in white gowns are playing with Chinese lanterns in this magical “secret” garden where lilies, carnations and roses appear enlivened by the nocturnal air and soft caresses of twilight.

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-86

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-86

This is my favourite painting at the moment and despite its, at first sight obvious, aesthetic appeal, it is much more than a visual delight. It awakens my every sense; I can almost hear the laughter of the fair-haired girls as they watch the lanterns with admiration and curiosity; and the enchanting melodies sung by the flowers; I can smell the thick and sweet fragrance of carnations, dearer to me than any perfume – I might pick a few for my vase; and I can almost feel the grass tickling my legs, oh it makes me giggle…

Gentle blades of grass seem to dance in the sweet, but fleeting melody of the dusk. White lilies laugh, their whiteness overpowering the shine of the lanterns, and relish in throwing mischievous glances around the garden, spreading gossips. Pink roses that spent their days in daydreams, have now awoken, keen not to miss all the fun that the night has to offer. Pretty yellow carnations, with thousands of little petals, each adorned with a divine perfume, are naughty little things. Girls’ white dresses, glistening in pink overtones from the dusky light, flutter in the evening breeze. Very soon, a game will begin; a game in which lanterns and moonbeams will be competing in beauty and splendour… As dusk turns into night, the lights of the moon will colour the garden in silver, secrets and dreams… When all is quiet and children are asleep, the flowers and the moon will converse. If you’re eager to know the mysteries of their language I suggest you to follow the trail of rose petals and silver all the way to one of the famous opium dens in Victorian era Limehouse, and once there, lie on the soft oriental cushions that glisten in dim lights and smokes arising and dancing in the tepid air, and wait for Morpheus to visit your soul in a slumber, for we all know that the poppy seeds never lie.

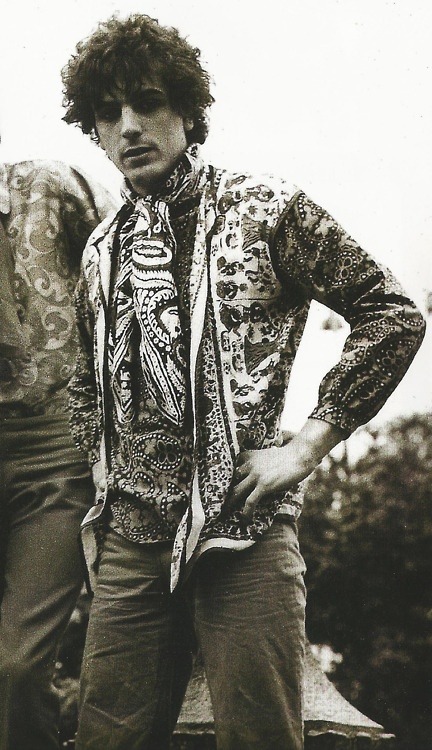

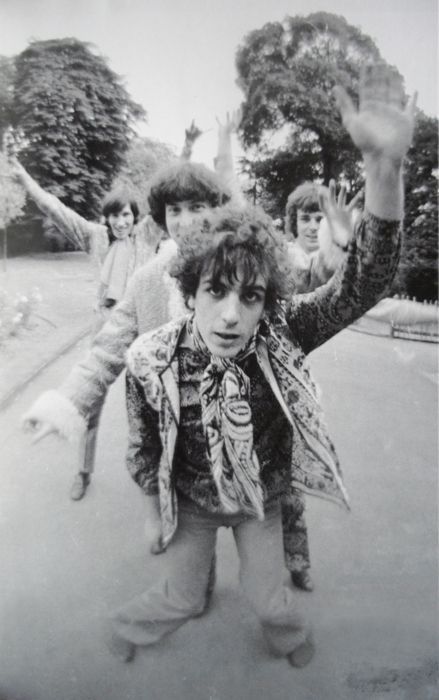

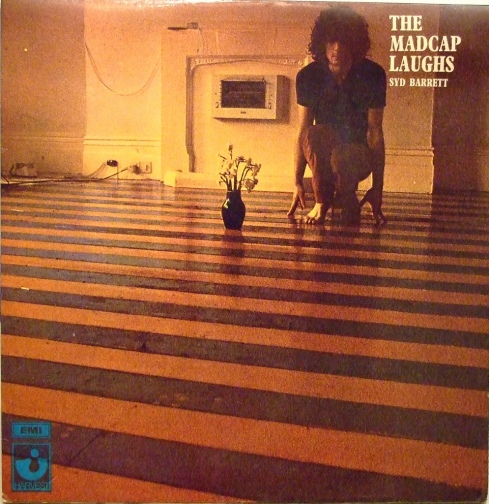

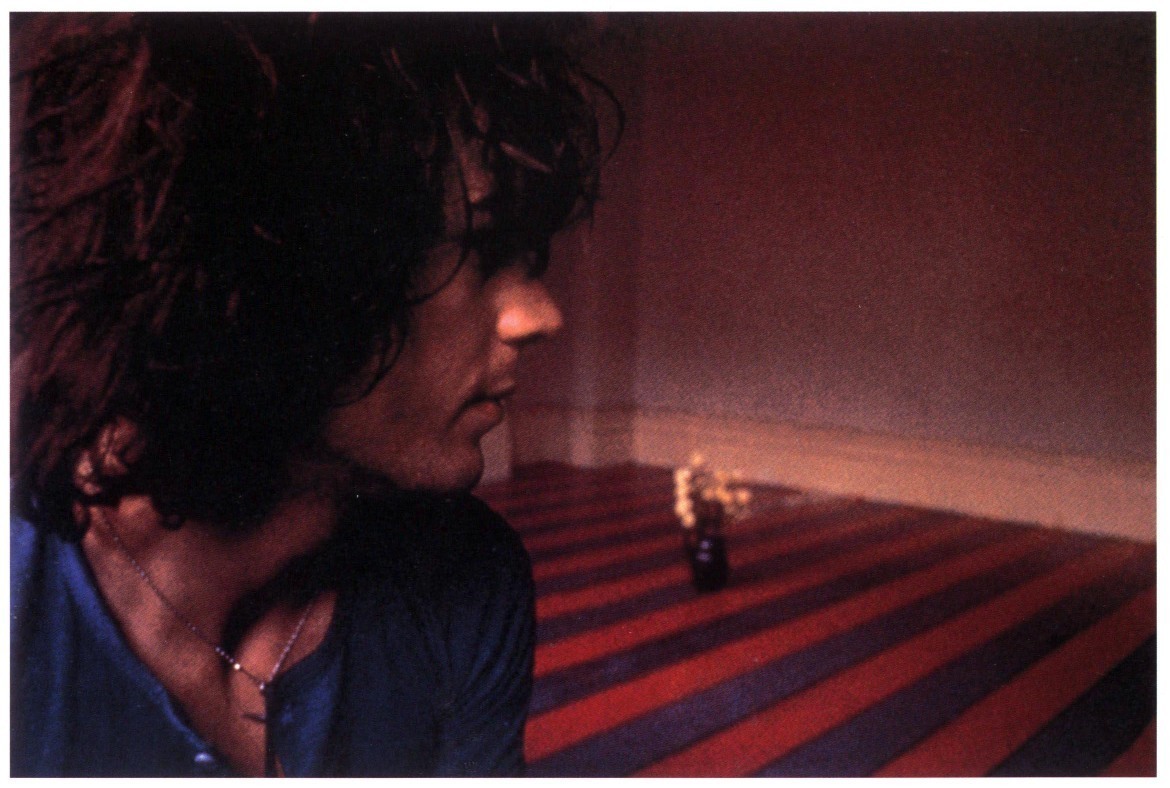

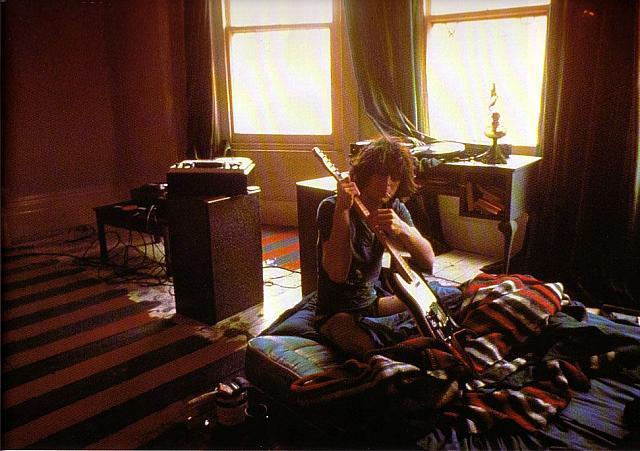

This painting is not only aesthetically pleasing, but it also reminds me of all sorts of things; first on the magical garden in the film Coraline (2009) where flowers are alive and naughty, and cat talks, then to the film Secret Garden (1993) which is based on book I’ve not yet read, and also on Syd Barrett and the lyrics to some of his song;”Flaming” and “Wined and Dined”.

John Singer Sargent, Garden Study of the Vickers Children, 1884

This is just an utterly beautiful and dreamy painting, but its technical aspects are equally interesting. First of all, the details and the very fine brushwork are amazing, and they irresistibly remind us of Pre-Raphaelites, and we know from the letters that Sargent was obsessed with them since the autumn of 1883, which he spent in Sienna.

The inspiration for the painting comes not from pure imagination but from a real event; one evening, in September 1885, he was sailing on a boat down the Thames with a friend and he saw Chinese lanterns glowing among trees and lilies. That special velvety pink-purplish dusky colour palette was achieved by directly gazing at nature in dusk, which meant it took him an awful lot of time to actually finish the painting. It was painted “en plein air” or “outdoors” which was typical for the Impressionists but uncommon for Sargent. He painted it in two stages; first from September to early November of 1885, and then in the late summer of 1886, and finished it sometime in October 1886. He spent only a few minutes painting each evening, at dusk, capturing its purplish glow, and then continue the next evening. He found the process of painting difficult, writing to his sister Emily: “Impossible brilliant colours of flowers and lamps and brightest green lawn background. Paints are not bright enough, & then the effect only lasts ten minutes.” And when autumn came, he would use fake flowers instead of real ones.

Two girls in the paintings are the 11-year old Dolly on the left, and her sister Polly, seven years old at the time; daughters of Sargent’s friend and an illustrator Frederick Barnard. They were chosen because of their hair colour. The original model was a 5-year old dark-haired Katherine, daughter of the painter Francis David Millet, and she was allegedly very upset that Sargent had replaced her. Poor girl! Also, the lovely title of the paintings comes from the refrain of the song “Ye Shepherds Tell Me” by Joseph Mazzinghi.

John Singer Sargent, Study for “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose”, 1885, oil on canvas, 72.4 x 49.5 cm, Digital image courtesy of private collection (Yale 875)

“Garden Study of the Vickers Children” is a some kind of a draught, a rehearsal for “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose”; both paintings were painted en plein air and both show children in a garden; childhood innocence was a theme often exploited in the arts of the 19th century because it appealed to the Victorian sentiments immensely, and both show the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites. However, in “Vickers Children” he uses bolder brushstrokes and the colour palette is all but magical; dull white, green and black. Sargent is said to have made more studies for “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose” than he did for any other of his paintings. Some of these studies you can see here, and they are simply gorgeous, they have such ardour and liveliness and there’s a real magic coming from those quick, visible brushstrokes; look at those lanterns, shaped in swift, round strokes of warm magical colours, and quick ones for the blades of grass and tints of rich red for flowers, ah…. This is the beauty that Dante must have had in mind when he said “Beauty awakens the soul to act.” These paintings awaken my soul!

Here you can listen a composition by Meilyr Jones inspired by this painting. Can you spare a second to think just how exciting it is to make a composition inspired by a painting, and such a beautiful painting?!

John Singer Sargent, Study for “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose”, 1885, oil on canvas, 59.7 x 49.5 cm, Digital image courtesy of private collection (Yale 872)

The scene irresistibly reminds me of John Everett Millais’s beautiful painting “Autumn Leaves”; both are very detailed with fine brushstrokes, set in a fleeting moment of the day – dusk, and show girls in nature, just in different seasons. Sargent’s painting is “magic”, while Millais’s is “melancholy”. Still, I feel a touch of sadness behind Sargent’s dreamy garden scene, brought on by the understanding of its transience and the fleeting nature of everything that is beautiful and magical in this world. Dusk lasts so shortly, and for a moment its charm will be replaced by darkness and chill air of night; Summer – which gives nature vivacity, colours and joy, will fall into the decadence of autumn. Unveil this beauty, the glow of lanterns and the fragrance of flowers, and you shall see decay – the garden in its future barren winter state. First the yellow leaves, then the white snowflakes, will cover the places where roses grew and nightingales sang their songs of love and longing; to quote Heinrich Heine:

“Over my bed a strange tree gleams

And there a nightingale is loud.

She sings of love, love only . . .

I hear it, even in dreams.”

And girls who are now innocent children will became adults, insensitive towards the beauty they once gleefully inhabited.

The very first glance at Sargent’s painting reminded me of this sentence from the book “Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd: Dark Globe”: “‘Wined and Dined’ has an undertow of sadness, sung in the most fragile of voices, lingering in twilight at an August garden party he never wanted to leave.” That beautiful, sad and poignant song dates from Syd’s days in Cambridge, when he was a happy man and life was idyllic, all “white lace and promises”, just like in the song of The Carpenters. This magical garden scene where flowers giggle, gossip and chatter in the purple veil of dusk, and lanterns glow ever so brightly is what I imagine Syd was in his mind; the August party he never wanted to leave… Thinking about it always makes me cry, it is so very sad. That “undertow of sadness”, this gentle fleetingness of the moment is exactly what I see in “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose” and in all of Syd’s songs.

In the acid-laced song “Flaming”, Syd sings of “watching buttercups cup the light, sleeping on a dandelion and screaming through the starlit sky” creating a visual scene that matches Sargent’s painting in its magic, but this childlike cheerfulness descended into a sad, wistful elegy to better days, “Wined and Dined“(version on the “Opel” sounds especially sad and poignant):

“Wined and dined

Oh it seemed just like a dream

Girl was so kind

Kind of love I’d never seen

Only last summer, it’s not so long ago

Just last summer, now musk winds blow…”

Move the flimsy veil from beauty, melancholy thou shall find.

John Everett Millais, Autumn Leaves, 1856

John Everett Millais, Autumn Leaves, 1856

They are things which are so intensely beautiful that I am not sure whether they produce as much pleasure as pain. They fill the heart with delight and longings all at once – such is the effect this painting has on me; first it lures me, and then it saddens me… But hush now, hush, reality, and let me enjoy the sweetness of this magical garden for another moment… Oh yes, I can feel the softness of the grass, see the lights of the lanterns, smell the carnations, can you?

Tags: 1885, 1886, 19th century, aestheticism, Amerian painter, American art, art, Beautiful, Beauty, carnation, children, Chinese lanterns, Colour, composition, Coraline (2009), dreams, dusk, En plein air, evening, Flaming, flowers, garden, Impressionism, Innocence, John Singer Sargent, Joseph Mazzinghi, lanterns, late summer, Lily, London, magic, Melancholy, Nature, night, oil on canvas, Oriental, outdoors, Painting, pink, Pink FLoyd, Pre-Raphaelites, purple, Rose, Sargent, Secret Garden, Syd Barrett, Thames, transience, twilight, victorian art, Victorian era, Wined and Dined, Ye Shepherds Tell Me

Henri Le Sidaner, Table with Lanterns in Gerberoy, 1924

Henri Le Sidaner, Table with Lanterns in Gerberoy, 1924