“My friend, you are laughing at me! You are making fun of a serious person who presently is consoling the child in a painting who has lost her bird, or the loss of anything that you wish? Can you see how beautiful she is! How interesting she is! I hate to trouble her.“

(Diderot)

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Young Girl Grieving Over Her Dead Bird, 1765

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Young Girl Grieving Over Her Dead Bird, 1765

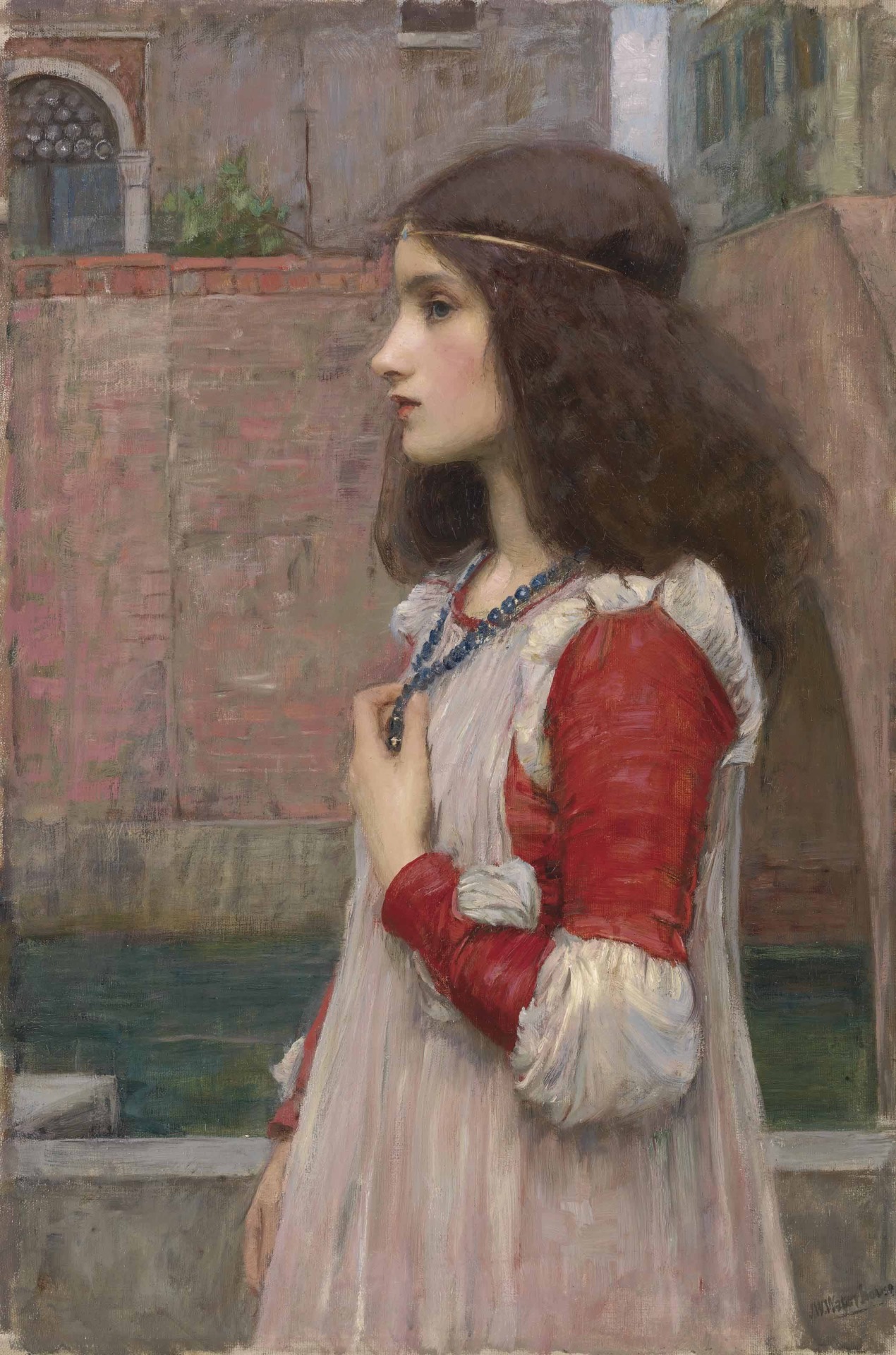

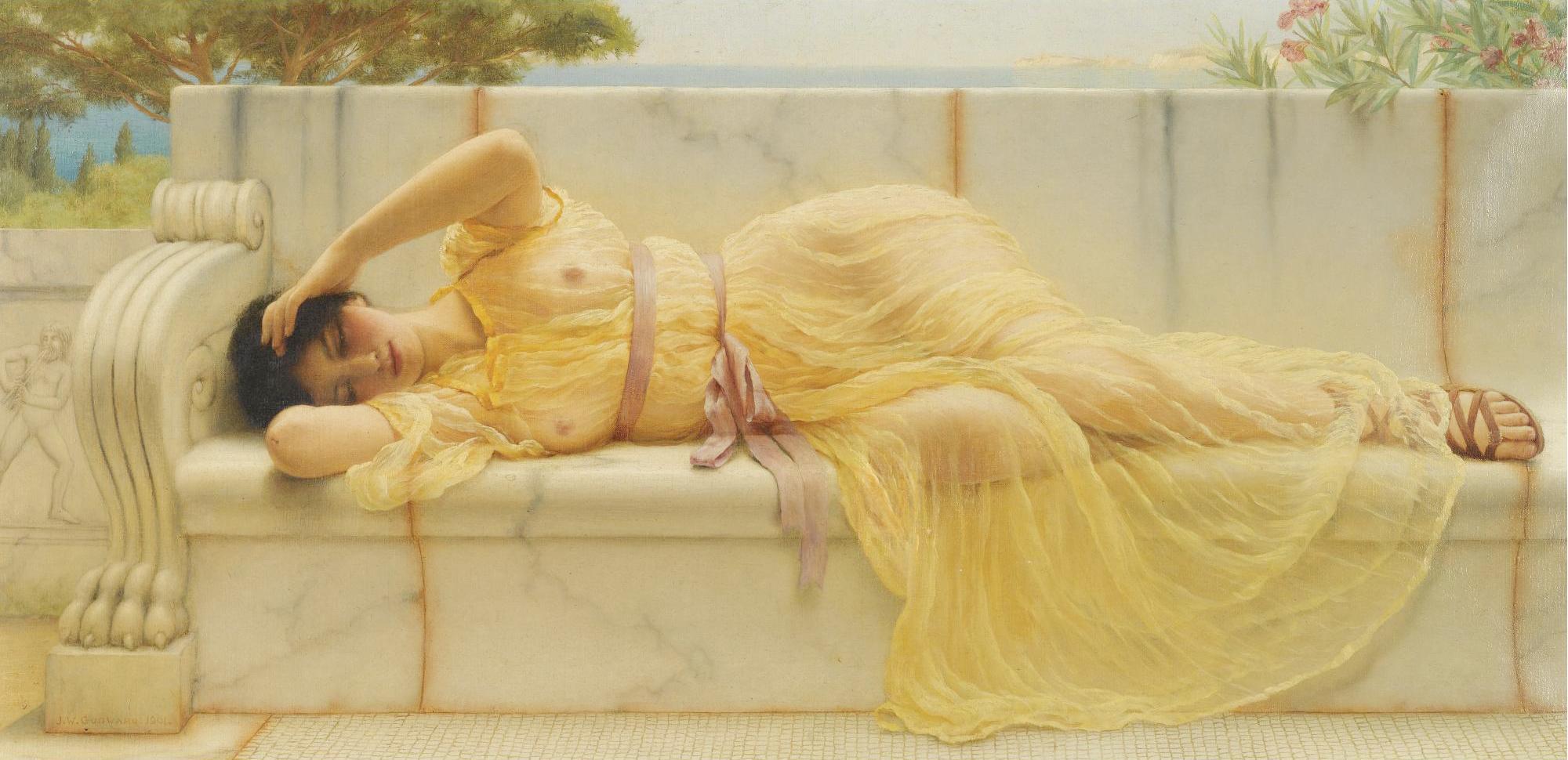

It is no secret that I have a soft spot in my heart for the wistful, pale, delicate and gentle ingénues that inhabit the canvases of Jean-Baptist Greuze. This eighteenth century painter is often overlooked and misunderstood, his paintings are often brushed off as sentimental and silly which is not true. Although, ironically, these paintings are the embodiment of the spirit that swept Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century: the Sentimetalism; a movement that emphasises the emotional appeal of art over cold reason and logic. Greuze’s girls have a way of moving the viewer and making him sympathise with their sorrow. In some paintings, the girl’s eyes are large and turned upwards, expressing sorrow and yearning, and other times, their face expressions are almost blank, and they captivate the viewer because we want to know the secret behind their face expression. The sweet oval face of the girl with a broken pitcher seems expressionless, and yet the aura around her is tinged with melancholy.

One such viewer who was very moved by a particular Greuze’s painting was the writer, philosopher and art critic Denis Diderot, who, I must add, also wrote the wonderful novel “The Nun”. On the salon of 1765, Diderot saw Greuze’s painting “The Young Girl Grieving Over Her Dead Bird”; an oval portrait of a girl lamenting the death of her beloved little bird. The girl is dressed in white, as Greuze’s girls usually are. The life of the pretty white bird surrounded by blue flowers is gone – never to be returned. Still, the subject of a painting isn’t as simple as it seems at first sight. It isn’t just about the dead bird, just as it is not about the broken eggs and broken mirrors and broken pitchers; these are the motives that you will see in the paintings bellow. Different motives here serve as metaphors that the viewers of the time surely understood. Diderot and some other critics saw these paintings as symbolic representations of the loss of innocence; a motif which had a great appeal to the buyers and collectors at the time. I can just imagine one of these girls as Marquis de Sade’s Justine, naive and easily exploited and abandoned, just like the girl in the painting “The Complaint of the Watch”; I already wrote a post about that painting which you can read here.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Dead Bird, 1800

Diderot, who was a friend of Greuze and loved his art, wrote a lenghtly monologue about the girl and the dead bird in his critic of the Salon of 1765 and here is what he wrote:

“When one sees this piece, one says: Delightful! If one stops, or that one returns, one says Delightful! delightful! Soon one is surprised to find oneself speaking to the child, consoling her. This is so true that this is what I remember saying to her at dif-ferent times. “But my little one, your pain is very deep and thoughtful! What does this dreamy sadness mean! What! For a bird! You aren’t crying, you are deeply wounded; and the thoughts carry your wounds. There my little friend, open your heart, open up your heart to me; tell me the truth, is it really the death of this bird that forces you to retreat into yourself? You’ve lowered your eyes; you’re not answering me. Your tears are ready to flow. I am not a father; I am neither indiscreet nor punishing… Ah! So, I realize that he loved you, he swore his love to you and he swore it a long time ago. He suffered a great deal: the way to see suffering of those we love… Let me continue; why are you closing my mouth with your hand? … Unfortunately, that morning your mother was absent. He came; you were alone; he was so handsome, so passionate, so tender, so charming! He had so much love in his eyes! So much truth in his expressions! He spoke those words that go straight to the heart! And while saying them, he was on his knees: I can still believe it. He held one of your hands; from time to time you felt the warmth of some tears which fell from your eyes and which ran the length of your arms.

Greuze, The Complaint of the Watch, 1770

“Still your mother did not return. It is not your fault; it your mother’s fault… He doesn’t want your pretty tears… But what I am saying to you is not to make you cry. Why are you crying? He made you a promise; he will not allow anything to happen to what he promised you. When one has been given the happiness to meet a charming child like you, and become one, so as to please him; it is for life…- and my bird?…- You smile”. (Oh! My friend, how pretty she is! Oh if you only could have seen how she laughed and cried!). I went on. “So! As for your bird! When one loses oneself, does one remember one’s bird? When it came time for your mother to return, the one you loved left. How happy he was, contented, and transported; how difficult it was for him to tear himself away from you! How you stare at me! I know all this. How many times he stood to leave and sat down again! How many times he said goodbye without leaving. How many times did he go only to return! I just saw him at his father’s: he is overwhelmingly happy, a happiness in which everyone participates, without putting up any resistance….”

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Broken Eggs, 1756

“And my mother? – Your mother? He had just left when she returned; she found you entranced, as you were a little while ago. One is always that way. Your mother was speaking to you, and you were not listening to what she was saying; she told you to do one thing and you did another. A few tears welled in the corners of your eyes; or you held them back, or you turned your head away to wipe them away furtively. Your unending daydreams made your mother impatient, and she scolded you and that gave you the opportunity to cry without restraint and to relieve your heart… Shall I continue, my dear? I fear that what I will say will continue your pain. You want me to? Your mother was upset with herself for making you unhappy; she came to you and took your hands, she kissed your forehead and cheeks, and you cried even more.”

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Young Woman, c 1780s

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Broken Mirror, 1763

“Your head fell onto her and your face which continued to blush, there just as it is doing now, was hidden in hers. How many calming things your mother said to you, and how much these kind words hurt! Furthermore your canary wanted to screech, to warn you, to call you, to bat its wings, to complain of your forgetfulness, you didn’t see him, you didn’t hear him; you were thinking other thoughts. His water or feed went unfilled and this morning the bird was no more… You are still staring at me; is there anything left for me to say? Oh, I hear, my sweet thing; that bird, it is he who gave him to you; oh well, he will find another just as beautiful… That is not all: your eyes are fixed on me, and are filling again with tears; what else is there? Speak I can’t guess…- What insanity. Don’t worry about anything, my poor girl; it can’t be; it won’t be!”

Greuze, The Broken Pitcher, 1771

“What! My friend, you are laughing at me! You are making fun of a serious person who presently is consoling the child in a painting who has lost her bird, or the loss of anything that you wish? Can you see how beautiful she is! How interesting she is! I hate to trouble her. In spite of that, it will not displease me to be the cause of her pain.The subject of this poem is so refined, that many have not heard it; they thought that this young girl was crying because of the canary. Greuze has already painted the same subject; he had placed a tall girl in white satin in front of a cracked mirror who appeared deeply saddened. Do you think that there will be as much gossip spoken about the young girl and her tears at the loss of a bird, than the sadness of the girl in the broken mirror in the last Salon? I am telling you that this child is crying over a different cause. First, you heard her, she agrees and her thoughtful pain says the rest. This pain! At her age and for a bird…“

Tags: 1765, art, art critic, bird, Denis Diderot, Diderot, France, French painter, girl, Greuze, Innocence, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Painting, Paris, Rococo, sad, salon, Salong of 1765, The Young Girl Grieving Over Her Dead Bird

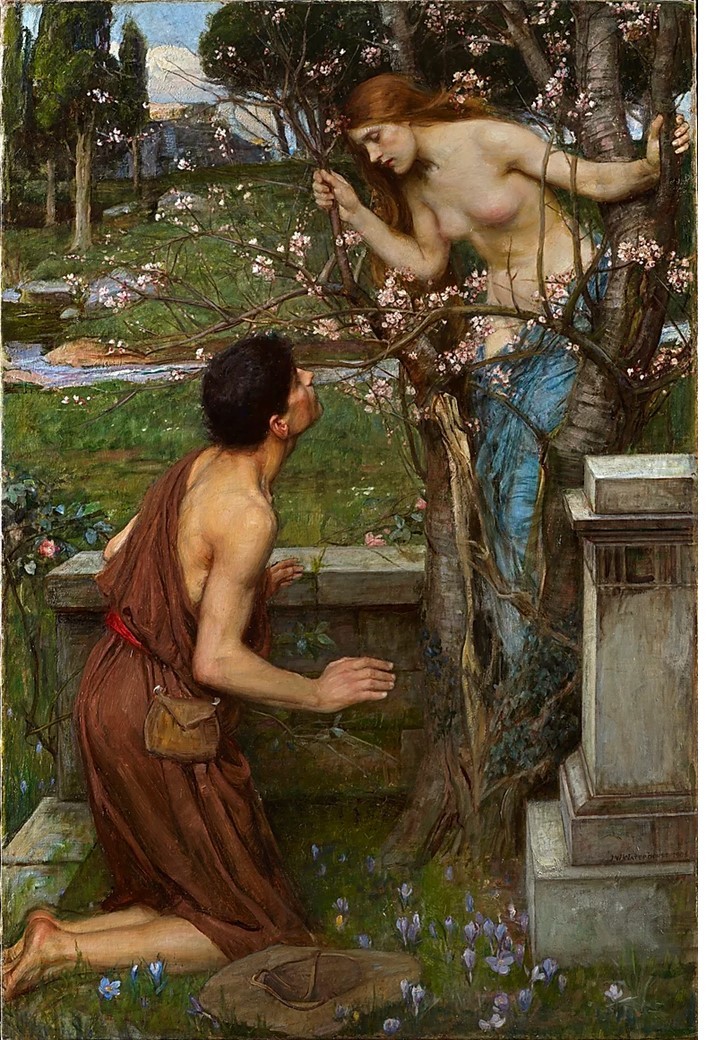

Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, Youth and the Lady, 1905

Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, Youth and the Lady, 1905 Picture found here.

Picture found here.