“The years had gone by like a dream.“

Edward Hopper, The Evening Wind, 1921, etching

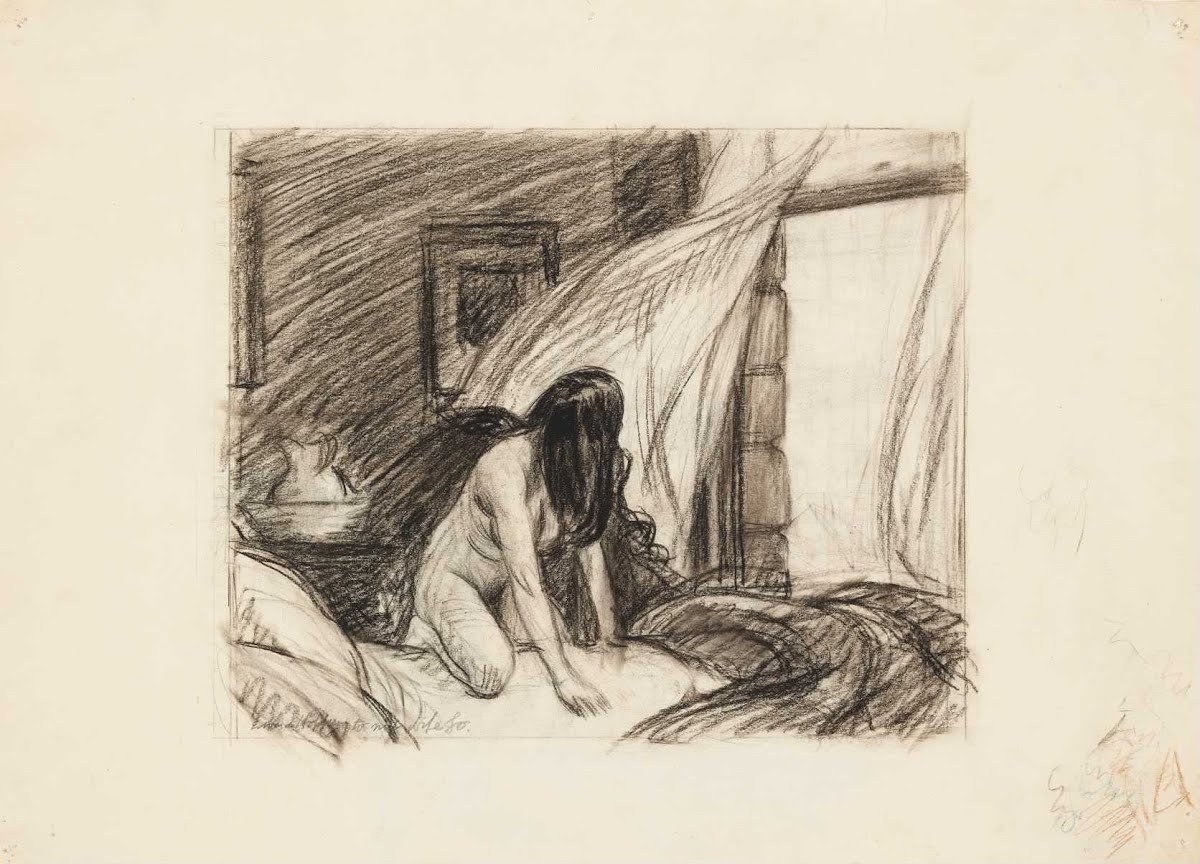

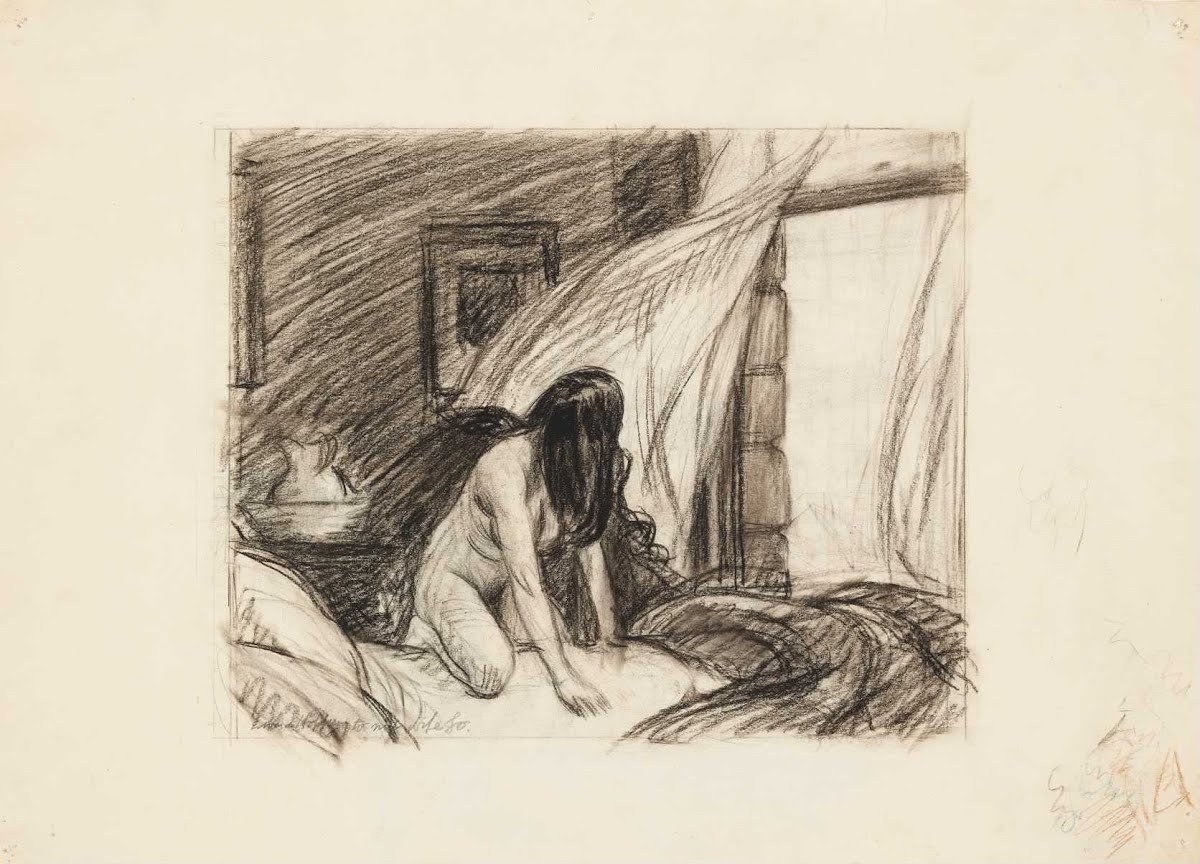

Edward Hopper, The Evening Wind, 1921, etching

I am usually not a great fan of etchings because I love colour, but this etching by Edward Hopper called “The Evening Wind” was particularly captivating to me. I had been wanting to write about it for some time now, but the timing never felt right, the words never seemed right… And now, reading Isaac Bashevis Singer’s novel “The Family Moskat” for the second time, in these grey winter mornings and candlelit winter evenings, the image of a naked woman in her bedroom, in the black and white form of an etching, instantly came to my mind upon reading the passage of the novel which I will share further on in the post. The etching is a portrait of a human figure in isolation, as is typical for Edward Hopper’s work. A naked woman is seen kneeling on her bed and looking towards the open window. The evening wind coming from the window is indicated by the movement of the curtains. It is a simple scene but striking visually and really atmospheric. There is a beautiful play of darkness and light in the scene. The woman is naked, but her face is hidden by her long hair. What is she looking at? And which wind opened the window, was it really the evening wind, or was it the breath of a long-lost lover, her beloved ghost still haunting her? Or was it the wind of nostalgia, bringing in a fragrance of memories and things long-lost. She seems startled as well as frozen in the moment; the wind startled her at first but then made her stop and ponder. The woman is wistful and alone, alone save for that evening wind, and this made me think of Hadassah.

The novel, published in 1950, follows the lives of the members of the Jewish Moskat family and others associated with it, in Warshaw, in the first half of the twentieth century. One of the main characters is Hadassah, the granddaughter of a wealthy family patriarch Meshulam Moskat, who is portrayed as a very shy and dreamy teenage girl in the beginning of the novel – quiet on the outside but passionate on the inside, but over time, through disappointments and love betrayals, Hadassah turns inwards and becomes as quiet and wistful as the forest that she lives nearby. “Still waters run deep” is something that comes to mind when I think of Hadassah, and someone had used that term to describe me one time. Hadassah is my favourite female character in the novel. She quickly falls in love with Asa Heshel, a disillusioned Jew who read Spinoza’s writings a bit too much. At first he comes off as a misunderstood, moody loner but very soon reveals a lack of character and horrible moral standards. I dispise him immensely, especially because of the way he treated Hadassah.

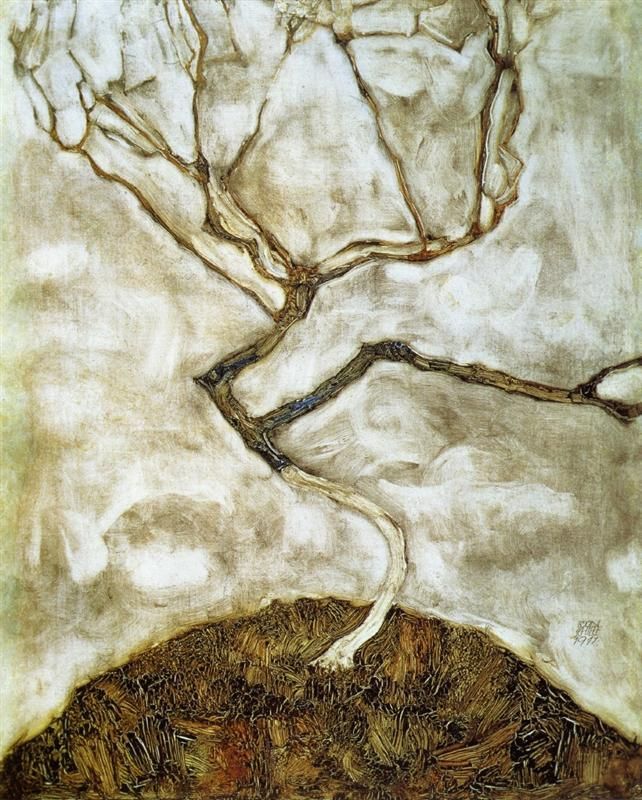

Edward Hopper, Study for Evening Wind, 1921, fabricated chalk on paper

In this passage of the novel, Hadassah is awoken from her slumber by the winter wind beating against the windows. Feeling wistful and nostalgic, she opens her old diary and starts flipping the pages (have I not been there myself…). She is not physically naked in this passage in the novel, but she is naked in spirit, in sorts, because Singer truly offers us a rare glimpse into the world of a dreamy young girl. The way her room, her diary, her thoughts and the conversation she is having with her mother about marriage are described, all feel so familar to me, as if my own. Pressed flower petals, yellowish diary pages, grammar books, dress laid over a chair, strange new feelings arising in your soul, unknown and unexplored territories of love, “the years have gone by like a dream”; this speaks to me in a language I can hear, to paraphrase the Smashing Pumpkins’ song “Thirty-Three”;

“On that same night Hadassah, too, was sleepless. The wind, blowing against the window, had awakened her, and from that moment she had not been able to close an eye. She sat up in bed, switched on the electric lamp, and looked about the room. The goldfish in the aquarium were motionless, resting quietly along the bottom of the bowl, among the colored stones and tufts of moss. On a chair lay her dress, her petticoat, and her jacket. Her shoes stood on top of the table-although she did not remember having put them there. Her stockings lay on the floor. She put both hands up to her head. Had it really happened? Could it be that she had fallen in love? And with this provincial youth in his Chassidic gaberdine? What if her father knew? And her mother and Uncle Abram? And Klonya! But what would happen now? Her grandfather had already made preliminary arrangements with Fishel. She was as good as betrothed.

Beyond this Hadassah’s thoughts could not go. She got out of bed, stepped into her slippers, and went over to the table. From the drawer she took out her diary and began to turn the pages. The brown covers of the book were gold-stamped, the edges were stained yellow. Between the pages a few flowers were pressed, and leaves whose green had faded, leaving only the brittle veined skeletons. The margins of the pages were thick with scrawls of roses, clusters of grapes, adders, tiny, fanciful figures, hairy and horned, with fishes’ fins and webbed feet. There was a bewildering variety of designs-circles, dots, oblongs, keyswhose secret meaning only Hadassah knew. She had started the diary when she was no more than a child, in the third class at school,in her child’s handwriting, and with a child’s grammatical errors. Now she was grown. The years had gone by like a dream.

She turned the pages and read, skipping from page to page. Some of the entries seemed to her strangely mature, beyond her age when she had written them, others naive and silly. But every page told of suffering and yearning. What sorrows she had known! How many affronts she had suffered-from her teachers, her classmates, her cousins! Only her mother and her Uncle Abram were mentioned with affection. On one page there was the entry: “What is the purpose of my life? I am always lonely and no one understands me. If I don’t overcome my empty pride I may just as well die. Dear God, teach me humility.” On another page, under the words of a song that Klonya had written down for her, there was: “Will he come one day, my destined one? What will he look like? I do not know him and he does not know me; I do not exist for him. But fate will bring him to my door. Or maybe he was never born. Maybe it is my fate to be alone until the end.” Below the entry she had drawn three tiny fishes. ‘What they were supposed to mean she had now forgotten. She pulled a chair up to the table, sat down, dipped a pen in the inkwell, and put the diary in front of her. Suddenly she heard footsteps outside the door.

Quickly she swung herself onto the bed and pulled the cover over her. The door opened and her mother came in, wearing a red kimono. There was a yellow scarf around her head; her graying hair showed around the edges.

“Hadassah, are you asleep? Why is the light on?”

The girl opened her eyes. “I couldn’t sleep. I was trying to read a book.”

“I couldn’t sleep either. The noise of the wind-and my worries. And your father has a new accomplishment; he snores.”

“Papa always snored. (…) Mamma, come into bed with me.”

“What for? It’s too small. Anyway, you kick, like a pony.”

“I won’t kick.”

“No, I’d better sit down. My bones ache from lying. Listen, Hadassah, I have to have a serious talk with you. You know, my child, how I love you. There’s nothing in the world I have besides you. Your father-may no ill befall him-is a selfish man.”

“Please stop saying things about Papa.”

“I have nothing against him. He is what he is. He lives for himself, like an animal. I’m used to it. But you, I want to see you happy. I want to see you have the happiness that I didn’t have.”

“Mamma, what is it all about?”

“I was never one to believe in forcing a girl into marriage. I’ve seen enough of what comes of such things. But just the same you’re taking the wrong road, my child. In the first place, Fishel is a decent youth-sensible, a good businessman. You don’t find men like him every day. … ”

“Mamma, you may as well forget it. I won’t marry him.”

(…) She went out and closed the door behind her. The moment she was gone, Hadassah flung herself out of bed. She went to the table, picked up the diary, thought for a moment, and then put it away in the drawer. She turned out the light and stood quietly in the darkness. Through the window she could see a heavy snow falling, the wind driving the flakes against the window pane.”

Tags: 1910s, 1921, American art, art, art blog, book, Edward Hopper, etching, Hadassah, Isaac Bashevis Singer, isolation, Jewish writer, Jews, Literature, modern life, Poland, quote, Realism, The Family Moskat, The Winter Wind, urban, Warsaw, wind, winter, winter in art, winter wind

Kay Nielsen, Illustration for The Story of a Mother, c. 1910

Kay Nielsen, Illustration for The Story of a Mother, c. 1910

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Harlequin and Columbine, 1716-1718

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Harlequin and Columbine, 1716-1718