“Eugenie was standing on the shore of life where young illusions flower, where daisies are gathered with delights ere long to be unknown.”

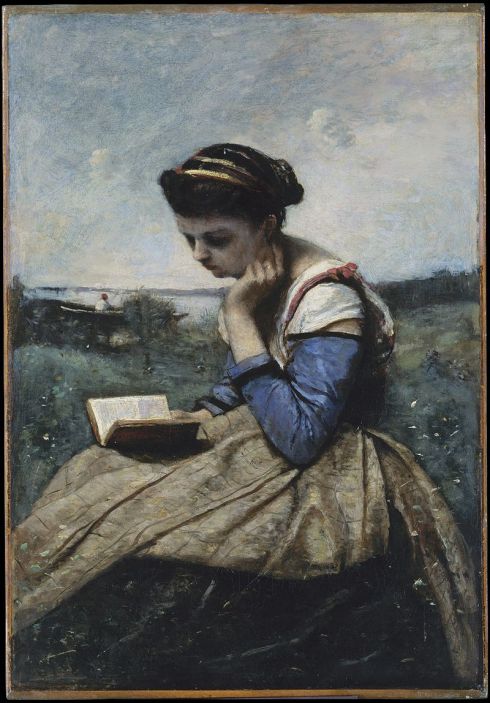

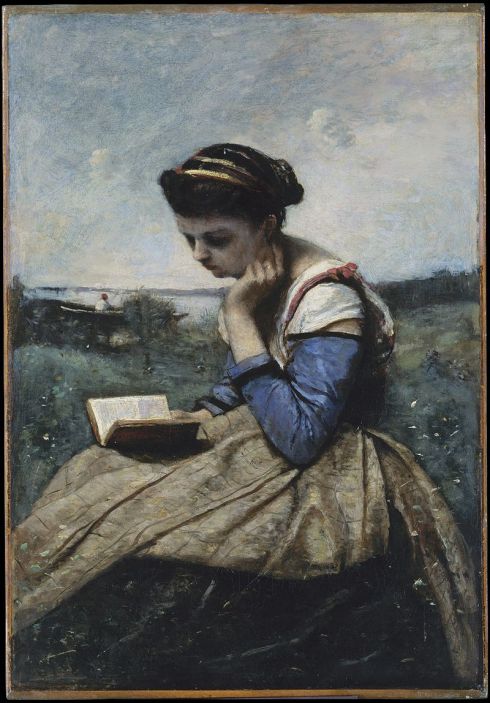

Camille Corot, Femme Lisant, 1869

Camille Corot, Femme Lisant, 1869

When I picked up Honore de Balzac’s novel “Eugénie Grandet” from my bookshelf I was hoping for hours of amusement, but I couldn’t anticipate just how touched to the core I would feel after finishing it. I had read his “Father Goriot” before and I found it a tad tedious to say the least, the flow of the novel too burdened by unnecessary descriptions of places and people, but “Eugenie Grandet” was the opposite; shorter and more to the point, more melancholy and intimate, and sad in its realism. If you are looking for a happy ending, do not read this book. The novel was first published in 1833 and it was part of Balzac’s “The Human Comedy”; a series of novels written from 1829 to 1848 that serve as a portrait of French society in the periods of Restoration (1815-30) and the July Monarchy (1830-48). Balzac even made subcategories for his novels and “Eugenie Grandet” was put in the “Scenes from provincial life” category. Interestingly, the novel was also translated by Dostoyevsky into Russian in 1843 and this translation marks the beginning of his literary career.

Zinaida Serebriakova, Collioure – Bridge with goats, 1930

“Eugenie Grandet” is a tale of a monotonous provincial life, greed and disillusionment set in the town of Saumur in 1819. The novel’s main character is a young woman called Eugenie Grandet who lives with her stingy old father Felix, a long-suffering mother who is her only friend, and a kind-hearted maid Nanon. Felix Grandet hides his wealth from everyone and forces his family to live on meager means and is keen on controlling every gram of butter and flour that is spent. There is no joy or love in the Grandet household. The novel in fact commences with a description of the Grandet house and this is important because the dark and gloomy house explains the pyschology of the characters, and later on it even becomes more important because it symbolises Eugenie’s life itself:

“There are houses in certain provincial towns whose aspect inspires melancholy, akin to that called forth by sombre cloisters, dreary moorlands, or the desolation of ruins. Within these houses there is, perhaps, the silence of the cloister, the barrenness of moors, the skeleton of ruins; life and movement are so stagnant there that a stranger might think them uninhabited, were it not that he encounters suddenly the pale, cold glance of a motionless person, whose half-monastic face peers beyond the window-casing at the sound of an unaccustomed step.“

Camille Corot, The Inn at Montigny les Cormeilles, 1830

The monotonous existence of the Grandet family is disturbed one day by an unexpectant visit; Felix’s nephew Charles came to Saumur, sent by his father, Felix’s estranged brother Guillaume who had spent the last thirty years living in Paris. Now, Guillaume is bankrupt and is planning to commit suicide and he sent his unaware son Charles to Saumur hoping that Felix will aid him in going to India. Charles is a handsome young man with an aristocratic elegance but like a true child of Paris he is too shallow and doesn’t believe in anything really. At first, he is devastated to learn of his father’s death and the unfortunate financial situation, but over time he and Eugenie fall in love. Before he leaves for India, they swear to remain true to one another and Eugenie gives him her collection of rare gold coins. The secret of Eugenie’s love brings the three women closer and all three are lonely creatures, birds trapped in Felix’s birdcage. But a sad love is better than no love it seems, for Nanon says: “If I had a man for myself I’d—I’d follow him to hell, yes, I’d exterminate myself for him; but I’ve none. I shall die and never know what life is.“ I found this passage about the differences between men and women interesting; while Eugenie was pining, waiting, yearning and suffering, at least Charles had agency in life:

“In all situations women have more cause for suffering than men, and they suffer more. Man has strength and the power of exercising it; he acts, moves, thinks, occupies himself; he looks ahead, and sees consolation in the future. It was thus with Charles. But the woman stays at home; she is always face to face with the grief from which nothing distracts her; she goes down to the depths of the abyss which yawns before her, measures it, and often fills it with her tears and prayers. Thus did Eugenie. She initiated herself into her destiny. To feel, to love, to suffer, to devote herself,—is not this the sum of woman’s life? Eugenie was to be in all things a woman, except in the one thing that consoles for all.”

Camille Corot, Girl Weaving a Garland, 1860-65

As a little digression, I have to say that while reading the novel I had the paintings of the French painter Camille Corot in mind, many of which were painted around the same time when the novel was published. Not only because of the motifs painted, but because of the dark, murky, and earthy colours. Charles’ arrival brought excitement into the Grandet household and Eugenie’s entire world had changed forever; once touched by love, the first time touched by love, a woman is never the same. For Eugenie, it was suddenly as if the flowers smelt better, the sky was bluer, and the future seemed brighter:

“Art thou well? Dost thou suffer? Dost thou think of me when the star, whose beauty and usefulness thou hast taught me to know, shines upon thee? – In the mornings she sat pensive beneath the walnut-tree, on the worm-eaten bench covered with gray lichens, where they had said to each other so many precious things, so many trifles, where they had built the pretty castles of their future home. She thought of the future now as she looked upward to the bit of sky which was all the high walls suffered her to see; then she turned her eyes to the angle where the sun crept on, and to the roof above the room in which he had slept. Hers was the solitary love, the persistent love, which glides into every thought and becomes the substance, or, as our fathers might have said, the tissue of life.“

Edvard Munch, Spring, 1889

On a New Year’s Day, as a family tradition, Felix asks his daughter to show him the coins but she refuses. As a punishment, he locks her in the room and gives her nothing but bread and water. Felix’s behavior, along with the austerity in the house, take a toll on his wife and she grows weak and eventually dies:

“Madame Grandet rapidly approached her end. Every day she grew weaker and wasted visibly, as women of her age when attacked by serious illness are wont to do. She was fragile as the foliage in autumn; the radiance of heaven shone through her as the sun strikes athwart the withering leaves and gilds them. It was a death worthy of her life,—a Christian death; and is not that sublime? In the month of October, 1822, her virtues, her angelic patience, her love for her daughter, seemed to find special expression; and then she passed away without a murmur. Lamb without spot, she went to heaven, regretting only the sweet companion of her cold and dreary life, for whom her last glance seemed to prophesy a destiny of sorrows. She shrank from leaving her ewe-lamb, white as herself, alone in the midst of a selfish world that sought to strip her of her fleece and grasp her treasures.

“My child,” she said as she expired, “there is no happiness except in heaven; you will know it some day.”

Camille Corot, The Letter, 1865

Eugenie takes on her mother’s duties in the house and life continues as monotonously as before. Felix dies and Eugenie is now a wealthy young woman. She is still hopeful and waiting for Charles… But circumstances have changed Eugenie, hardened her even against her will:

“At thirty years of age Eugenie knew none of the joys of life. Her pale, sad childhood had glided on beside a mother whose heart, always misunderstood and wounded, had known only suffering. Leaving this life joyfully, the mother pitied the daughter because she still must live; and she left in her child’s soul some fugitive remorse and many lasting regrets. Eugenie’s first and only love was a wellspring of sadness within her. Meeting her lover for a few brief days, she had given him her heart between two kisses furtively exchanged; then he had left her, and a whole world lay between them. (…) In the life of the soul, as in the physical life, there is an inspiration and a respiration; the soul needs to absorb the sentiments of another soul and assimilate them, that it may render them back enriched. Were it not for this glorious human phenomenon, there would be no life for the heart; air would be wanting; it would suffer, and then perish. Eugenie had begun to suffer. For her, wealth was neither a power nor a consolation; she could not live except through love, through religion, through faith in the future. Love explained to her the mysteries of eternity. (…) She drew back within herself, loving, and believing herself beloved. For seven years her passion had invaded everything.”

Camille Corot, A Pond in Picardy, 1867

Seven years pass before his return; Charles is now wealthy and excited to show off in Paris, but the pure feelings of love and tenderness that he felt towards Eugenie had all faded. Travel has changed him; he lost his moral compass, if he ever had it in the first place, and “his heart grew cold, then contracted, and then dried up.” He writes to Eugenie about his change of heart, telling her also that her provincial lifestyle is not compatible with his life, and that love is merely an illusion really.

“…travelling through many lands, and studying a variety of conflicting customs, his ideas had been modified and had become sceptical. He ceased to have fixed principles of right and wrong, for he saw what was called a crime in one country lauded as a virtue in another. In the perpetual struggle of selfish interests his heart grew cold, then contracted, and then dried up. The blood of the Grandets did not fail of its destiny; Charles became hard, and eager for prey. (…) If the pure and noble face of Eugenie went with him on his first voyage, like that image of the Virgin which Spanish mariners fastened to their masts, if he attributed his first success to the magic influence of the prayers and intercessions of his gentle love, later on women of other kinds, —blacks, mulattoes, whites, and Indian dancing-girls,—orgies and adventures in many lands, completely effaced all recollection of his cousin, of Saumur, of the house, the bench, the kiss snatched in the dark passage. He remembered only the little garden shut in with crumbling walls, for it was there he learned the fate that had overtaken him; but he rejected all connection with his family… Eugenie had no place in his heart nor in his thoughts, though she did have a place in his accounts as a creditor for the sum of six thousand francs.“

Camille Corot, Portrait of Madame Charmois, 1837

Eugenie marries a man Cruchot whom she doesn’t love and who only wants her wealth but only under the condition that the marriage is not consummated. Cruchot too then dies. Eugenie is left alone in that dark and drab house which is now a reflection of her life. The novel is really a tale of Eugenie’s rite of passage; she grows from an innocent and inexperienced provincial girl who knows nothing about the world into a mature and wise woman whose heart is closed and whose tender feelings have all hardened. The disillusionment in love brought on a disenchantment with the world and life itself. She is alone and lonely, with no one but Nanon to love her, but Nanon too will die one day. When I was reading these kind of novels years ago, before I knew what love or loss were, I read them with a mix of curiosity and a detached sadness. These days, though, it is impossible not to be touched by such stories as Eugenie’s. Once you get your hopes high and life disappoints, it is almost impossible to raise them as high again. Life etches itself into your soul and it is hard to be blind and naive again and see things through rose-tinted glasses. Eugenie’s tale isn’t even sad, it’s just realistic. This is life; love brings disappointment and loneliness is always a step away. The last page leaves us with an image of Eugenie of continuing her father’s stingy habits because it is something familiar to her, but in truth, the money had brought her nothing but misery:

“Madame de Bonfons became a widow at thirty-six. She is still beautiful… Her face is white and placid and calm; her voice gentle and self-possessed; her manners are simple. She has the noblest qualities of sorrow, the saintliness of one who has never soiled her soul by contact with the world; but she has also the rigid bearing of an old maid and the petty habits inseparable from the narrow round of provincial life. In spite of her vast wealth, she lives as the poor Eugenie Grandet once lived. The fire is never lighted on her hearth until the day when her father allowed it to be lighted in the hall, and it is put out in conformity with the rules which governed her youthful years. She dresses as her mother dressed. The house in Saumur, without sun, without warmth, always in shadow, melancholy, is an image of her life. She carefully accumulates her income, and might seem parsimonious did she not disarm criticism by a noble employment of her wealth. (…) that noble heart, beating only with tenderest emotions, has been, from first to last, subjected to the calculations of human selfishness; money has cast its frigid influence upon that hallowed life and taught distrust of feelings to a woman who is all feeling.

“I have none but you to love me,” she says to Nanon.”

Tags: 1833, 1869, art blog, Balzac, book, book review, Camille Corot, Eugenie Grandet, French writer, Honore de Balzac, Literature, novel, provincial town, Realism, sad

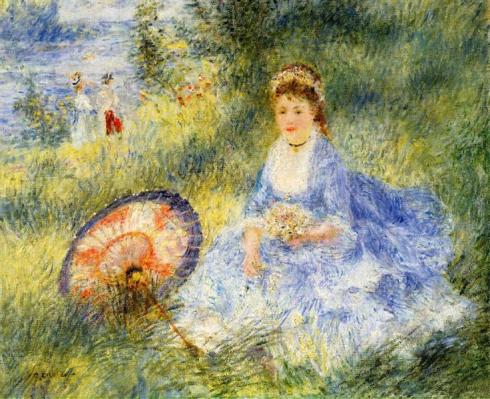

Renoir, Young Woman with a Japanese Umbrella, 1876

Renoir, Young Woman with a Japanese Umbrella, 1876