“He was still too young to know that the heart’s memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past.”

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Lovers, 1875

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Lovers, 1875

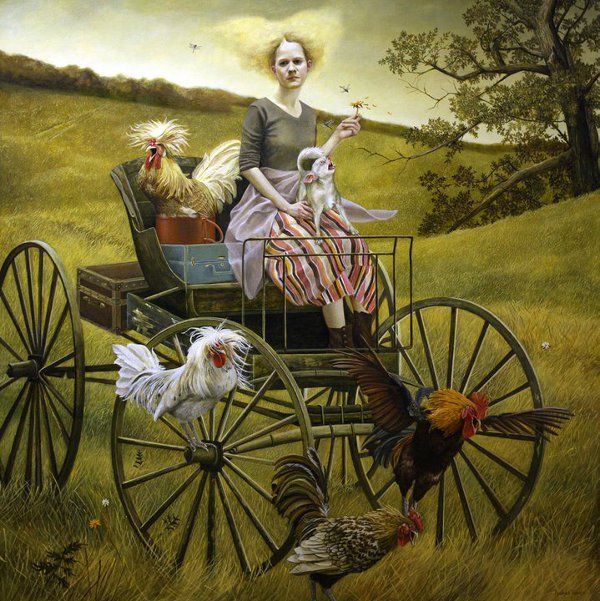

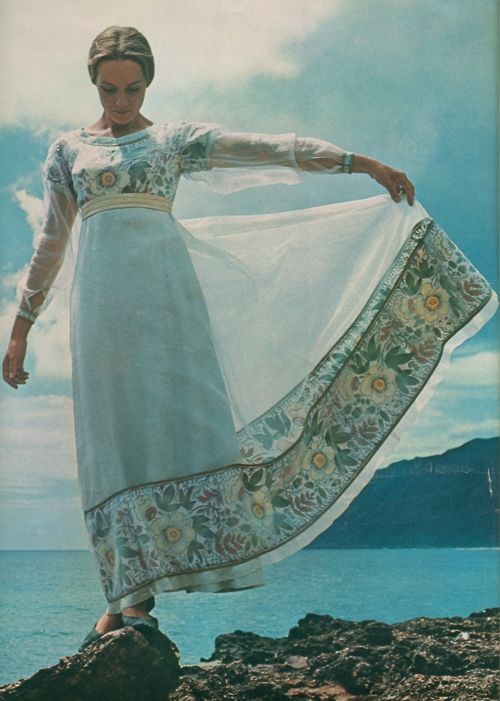

The other day I had decided to start rereading Gabriel García Márquez’s novel “Love in the Time of Cholera”, published in 1985, because I had fond memories of reading it for the first time a few years ago. My favourite is still his novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude”, but the persistant and dedicated love of Florentino Ariza, played by Javier Bardem in the film, towards Fermina Daza is truly something special. The novel is set somewhere in the Caribbean, as is always the case with Márquez’s novels, and, again, as typical for Márquez, the realism and magic meet and mingle, or more precisely, the realism and nostalgia in the case of Doctor Urbino, one of the main characters in the novel and Fermina’s husband, who has just returned from Europe where he studied. There is a discord betweeen his memories of the Caribbean, his native place, and of the realism that awaits him there upon his return; everything is disappointing in one way or another, smaller and more boring and yet, in his mind, whilst strolling the streets of Paris, that same Caribbean was magical: verdant and fragrant and alive. This is something I am sure most of us have experienced at some point in our lives, and yet again and again I find myself powerless against the claws of nostalgia ripping into my very soul. Here is the passage from the novel describing the very feeling:

“In Paris, strolling arm in arm with a casual sweetheart through a late autumn, it seemed impossible to imagine a purer happiness than those golden afternoons, with the woody odor of chestnuts on the braziers, the languid accordions, the insatiable lovers kissing on the open terraces, and still he had told himself with his hand on his heart that he was not prepared to exchange all that for a single instant of his Caribbean in April. He was still too young to know that the heart’s memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past. But when he stood at the railing of the ship and saw the white promontory of the colonial district again, the motionless buzzards on the roofs, the washing of the poor hung out to dry on the balconies, only then did he understand to what extent he had been an easy victim to the charitable deceptions of nostalgia.

The ship made its way across the bay through a floating blanket of drowned animals, and most of the passengers took refuge in their cabins to escape the stench. The young doctor walked down the gangplank dressed in perfect alpaca, wearing a vest and dustcoat, with the beard of a young Pasteur and his hair divided by a neat, pale part, and with enough self-control to hide the lump in his throat caused not by terror but by sadness. On the nearly deserted dock guarded by barefoot soldiers without uniforms, his sisters and mother were waiting for him, along with his closest friends…

A short while later, suffocating with the heat as he sat next to her in the closed carriage, he could no longer endure the unmerciful reality that came pouring in through the window. The ocean looked like ashes, the old palaces of the marquises were about to succumb to a proliferation of beggars, and it was impossible to discern the ardent scent of jasmine behind the vapors of death from the open sewers. Everything seemed smaller to him than when he left, poorer and sadder, and there were so many hungry rats in the rubbish heaps of the streets that the carriage horses stumbled in fright. On the long trip from the port to his house, located in the heart of the District of the Viceroys, he found nothing that seemed worthy of his nostalgia. Defeated, he turned his head away so that his mother would not see, and he began to cry in silence.

The former palace of the Marquis de Casalduero, historic residence of the Urbino de la Calle family, had not escaped the surround ing wreckage. Dr. Juvenal Urbino discovered this with a broken heart when he entered the house through the gloomy portico and saw the dusty fountain in the interior garden and the wild brambles in flower beds where iguanas wandered, and he realized that many marble flagstones were missing and others were broken on the huge stairway with its copper railings that led to the principal rooms.”

Winslow Homer, Along the Road, Bahamas, 1885