“A beautiful sense of melancholy and nostalgia permeates everything as the natural world prepares to surrender itself over to winter.“

(Andrea Kowch)

Andrea Kowch is one of my favourite contemporary artists. All of her paintings possess a dreamy and mysterious mood that is bound to make one curious. The everyday plain banality of the countryside is transformed into a scene out of some magic realism novel. Without a doubt, Kowch possesses a rich imagination and she has the artistic skill to match it. I mean, her technique and the detailed approach are impessable. In one interview she said that painting was something meditative for her, she even calls it a “self-therapy”: “The process of being a painter has served as a form of self-therapy for me, in that all the hours I spend painting, I also spend thinking and allowing myself to fully feel my deepest emotions and know myself. I come out of each piece transformed in a new way each time. People need encouragement to get in touch with their realest emotions and embrace them. What some may see in my work as “intense” or “disturbing”, others may see as beautiful and liberating. It happens all the time, and neither interpretation is correct or incorrect.”

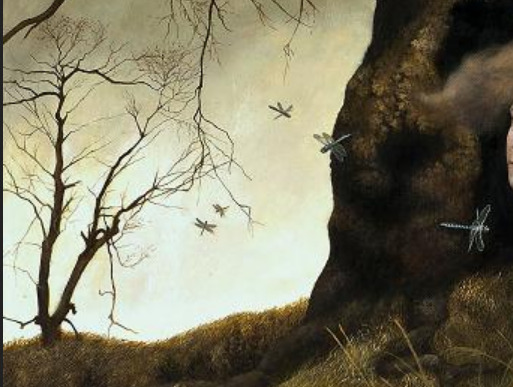

A landscape with two women and a tree in the background, so simple in visual motives and yet so mysterious in the mood it conveys. The ordinary becomes extraordinary under Kowch’s brush. Scenes of magic realism indeed, but an interesting thing is that in novels such as Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” no matter the magic realism the plot and the characters still needs to be explained and it needs to make sense to the reader. On the other hand, Kowch doesn’t need to explain anything in her art; why are these ladies sitting here so near to the jumping frogs, why are they dressed so lightly considering the cold weather indicated by the bare autumnal tree behind them? This is all left to us to interpret and this is the beautiful but also the mysterious side of visual art.

The models for all of Kowch’s paintings are her friends. These two women are sitting casually on the meadow; their bodies are turned to different sides but interestingly they are both looking on the left. What is so interesting over there that we cannot see? The frogs are also casually jumping around but the women don’t seem to mind it the least bit. They appear to be fixated on that something which is beyond our sight. Kowch’s female figures always appear frozen, spellbound even, and this just serves to further the mystery. They are wearing their petticoats, tights and boots but their shoulders are bare. How are they not cold and shivering?

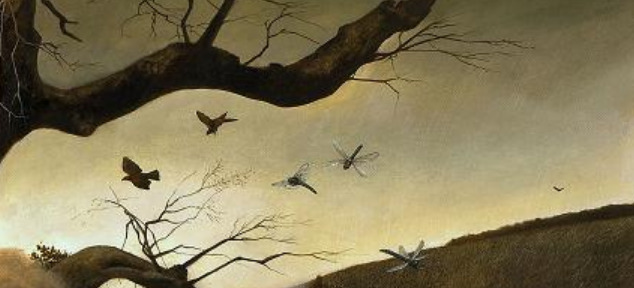

The tree in the background, completely bare and its spooky branches reaching towards the “skies that are ashen and sober” are a good indication of the autumnal weather. And this doesn’t appear to be the golden sunny autumnal day, no, this is the portrait of deep autumn’s doom and gloom. The crows in the background flying around the tree and the fireflies dancing and flying around the women further perpetuate the painting’s mysterious, dreamy charms. I like the line which marks the end of the meadow and behind it we see faint traces of vanilla yellow sunlight coming from afar. It creates a beautiful contrast between the lightness coming from the background and the swampy, frog and fireflies laden meadow bellow.

The tree is a definite ominous element and makes me think of something we would find in Edgar Allan Poe’s stories. I also love the way Kowch paints blades of grass; she almost gives individual identity to every single piece of grass or wheat or whatever else she is painting. She truly creates a sense of texture. Perhaps a little bit this meadow and the girls bring to mind Andrew Wyeth’s painting “Christine’s World” from 1948, but the atmosphere is different.

Kowch’s painting style may perhaps even be described as “dark fairytale” because both elements are all-pervading in her canvases; the dark, gloomy, almost Gothic vibes with the elements of fairytales and storytelling. In her own words: “I loved fairy-tales as a girl, and still do. They were an escape into a romantic, mysterious, and magical world. The classic tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm were the first to charge my imagination as a child. I later discovered and fell in love with the art of Arthur Rackham and Howard Pyle… I’ve always been drawn to and intrigued by stories that are a bit twisted; the ones containing strange characters and a prevailing sense of impending danger. Perhaps that’s why my paintings often carry a similar feeling. There’s always an aspect of something unknown about to happen. The story is never fully revealed, it simply continues on, each painting serving as the next page or chapter.”

Some motives that are bound to be seen in nearly all of Kowch’s paintings are the countryside setting, whether it’s the fields of corn, wheat or barley, or the meadows littered with dandelions and other flowers, strange trees with bare and twisted branches, old barns or cottages; women, often with pale wistful faces, messy hair and strange, old-fashioned clothes, then animals such as ravens, seagulls, frogs, turkeys, dogs, roosters, crickets, grasshoppers, rabbits, even a guinea pig in one painting. The colours she uses are distinctly autumnal. She weaves the dreamy tapestries of her imagination in shades of fern and moss green, garnet red, cider, amber and marmalade orange, mustard yellow, ash grey, cinnamon brown, boysenberry purple…

Kowch is not shy when it comes to admitting her love for autumn: “Autumn is my favorite season. The scents in the air, changing landscapes, colors, mood of the sky, air of ominous foreshadowing… It’s when the earth begins to truly bare its soul. It’s when I can feel the bones, core, and essence of nature. There is also a cozy and mysterious quality that inspires me to turn inward and relish solitude and explore deeper feelings. The heavy, rolling clouds spark moods in me which translate into the work. A beautiful sense of melancholy and nostalgia permeates everything as the natural world prepares to surrender itself over to winter. All of those things are very poignant, and speak to my soul in many profound ways.”

All the quotes in this post are from an interview which you can read here.