“I’d done it before

(and doubtless I’ll do it again,

sooner or later)

woke up with a head on the pillow beside me – whose? –

what did it matter?

Good-looking, of course, dark hair, rather matted;

the reddish beard several shades lighter;

with very deep lines around the eyes,

from pain, I’d guess, maybe laughter;

and a beautiful crimson mouth that obviously knew

how to flatter…

which I kissed…

Colder than pewter.

Strange. What was his name? Peter?

Simon? Andrew? John?

(….)

In the mirror, I saw my eyes glitter.

I flung back the sticky red sheets,

and there, like I said – and ain’t life a bitch –

was his head on a platter.”

(Carol Ann Duffy, Salome)

Gustav Adolf Mossa, Salome, 1901

Gustav Adolf Mossa, Salome, 1901

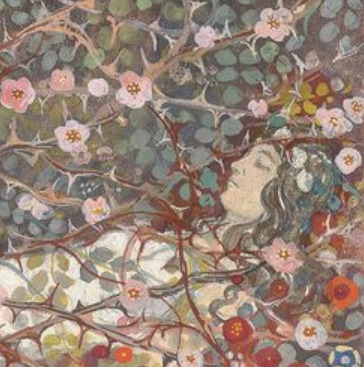

Gustave Moreau painted many and many depictions of the legendary dancer and femme fatale Salome, and while I enjoy the rich, jewel-toned, dense and claustrophobic mood portrayed in those paintings, I think that Gustav Adolf Mossa’s watercolour of Salome is particularly striking because it is both more simple and more twisted than any of Moreau’s paintings. Salome is portrayed at once as a dangerous, blood-thirsty seducer and destroyer of men, and, as an innocent little girl. It is as if her girlhood and womanhood are having a dance. She is shown kneeling on the bed, dressed in a flimsy white gown, a nightgown most likely, holding a big sword and licking the blood off of it. Behind her are four large blooming pink roses with rusty thorny stems and in each rose is a decapitated head of a man – the head of St John, which was what she had requested as a gift for her beautiful dance. The heads, still oozing blood and with horrified face expressions, are truly a sight to see, but Salome, in her dainty white bed, doesn’t seem disturbed at all. She is girlishly unaware of the blood and screams. Her face and body are delicate, pale and doll-like. Beside her on the bed we can see a black comb and a doll, as if she were a little girl who has done nothing wrong. A pretty little coquette is what she is. Her thigh and bosom are peeking out in a seductive manner and there are opulent rings on her slender fingers – womanly things. And yet there are little black bown on her dress, and one in her hair – a girlish thing.

French Gustav Adolfo Mossa spent his late teens and most of his twenties painting in a Symbolist style and so that first artistic period in Mossa’s oeuvre is called the “Symbolist period” and it lasted from about 1900 to 1911. Later, upon moving to Bruges, he discovered Flemish paintings and his art drifted in another direction. In his Symbolist phase Mossa created a macabre and disturbing yet vibrant world littered with femme fatales and saints, heroes and heroines from Shakespeare, and just random skeletons. Mossa was introduced to the Symbolist art at the Exposition Universelle which he visited in 1900 and after that moment all the inspiration that was mounting in his teenage soul, taken from Art Nouveau and the literary works of Charles Baudelaire, Joris-Karl Huysmans and Mallarmé, suddenly flourished in these watercolours which are all so captivating and full of interesting details. I always felt drown to the spirit of Symbolism, and yet the way these ideas were manifested in the visual arts wasn’t very appealing to me. Now, in the art of Mossa, I found what I was looking for. I love how the classic, well-known themes in art are transformed by Mossa into a festival of blood, bones, lust and roses. The delicacy of watercolour mixed with somewhat gruesome or eerie themes is especially entrancing. The beauty of the Symbolist phase of Mossa’s art is that it both disturbs and bewilders the soul.