“There is nothing you can

see that is not a flower; there

is nothing you can think that

is not the moon.”

(Mastuo Basho)

Namiki Hajime, Weeping Cherry Tree 9, 2008

Namiki Hajime, Weeping Cherry Tree 9, 2008

Even before the calender announces its arrival, the wonderful season of spring starts in my heart. The moment I behold the first blooming tree. The yesterday’s bare branches suddenly adorned with countless tender little blossoms. The thrill! The ecstasy! The rapture!

These past two weeks or so I have been taking great delight in seeing the kwanzan cherries finally in bloom, their petals ever so soft and ever so pink. Yesterday afternoon I walked passed some kwanzan cherry trees and I simply had to stop and admire their beauty for awhile. Their branches heavy from the rain were leaning lower than ever, the pink colour of the blossoms was even more radiant against the greyness of a rainy day than it would be on a sunny day, each drop of rain on the blossoms glistened like a little diamond… The pavement was wet from the rain and littered with pink blossoms, and so were the little puddles upon which the blossoms were floating like little boats. It was a magical moment, the kind you wish could linger on and on, but it cannot just as the kwanzan cherries will not be in bloom all year long, not even a month long. The beauty of blooming trees is the ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ kind of beauty when one compares the length of the blooming time to all the other time when it doesn’t. The rainy days always seem to linger while the sunny ones just pass me by. For months the bare tree branches have been poking me in the eye with their drab, sad appearance and now, when they are dressed up in white and pink blossoms, when they are such a joy to behold, now this will pass… These blossoms are so delicate that even a slight breeze can, and does, tear them, but still, the greatest terror for these delicate, blooming beauties is time. The beauty of the early blossoms of spring lies in their impermanance. I enjoy gazing at them because I know that in a week, or two, or three, all these pink petals will have fallen off. There is something heart-wrenching about it, how unstoppable it is, the transience. And yet the trees accept it, this change, better than I do, it seems. They live on peacefully, whether their branches are full of blossoms, green leaves, clad in auburn and yellow, or completely bare. What can we do then, to capture these delicate, transient beauties?

By Shodo Kawarazaki

Kotozuka Eiichi, Drooping Cherry Blossoms, 1950

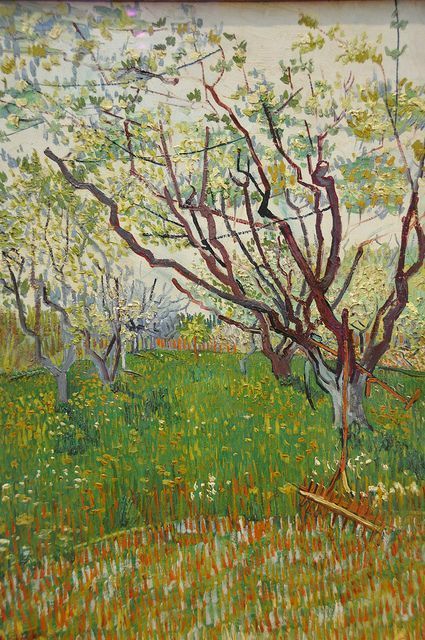

Vincent van Gogh, Almond Blossom, 1890

Of course, as I do with every feeling in life, whether it’s love or sadness, I turn to art and I have spent many pleasant moments gazing at all these Japanese ukiyo-e prints with a motif of blossoms or even the festivals and celebrations surrounding the cherry blossom season. And of course I had to include this painting by Vincent van Gogh as well because he also desperately tried to capture the fleeting beauty of almond blossoms. And to finish the post here is a passage from Andrew Juniper’s book “Wabi-sabi: the Beauty of Impermanance” which connects the almost inseparable motifs of cherry blossoms and transience:

“Few factors hold more sway on a national character than the weather. The temperate climate that Japan enjoys brings some of themost wonderful changes of season, and it is to these that the Japanese focus their interests and energies. Blessed with some of the most beautiful trees in the world, Japan in autumn or spring can be truly breathtaking, and the cherry blossoms have become one of the defining features of the Japanese calendar. During the brief time that the millions of cherry trees in Japan blossom, hundreds of thousands of small and large parties are held underneath them. Sake is drunk, songs are sung, and the fleeting beauty of the blossoms is enjoyed to the full. They are enjoyed in the knowledge that at the whim of the wind or rain nature can withdraw their beauty at a moment’s notice. It is like a celebration of our own fleeting lives and is another way in which the Japanese can indulge their love of things impermanent. The changing of the seasons has always been a reoccurring theme in Japan’s art and is often used to illustrate our own passage of time. For example, spring is often used as a euphemism for the sexual stage of life (the word prostitute is actually made from the three characters “selling spring woman”).“

Utagawa Kunisada, Woman Walking under Cherry Blossoms at Night, c 1840s

Toyohara Chikanobu (1838 – 1912), Cherry Blossoms Party at the Chiyoda Palace (Chiyoda Ooku Ohanami), 1894

Yoshikawa Kanpo, Cherry Blossom at Night in the Maruyama Park, ca. 1925

Toyohara Chikanobu, Evening Cherry Blossoms – Ladies of Chiyoda Palace, 1896

Jokata Kaiseki , Mt Fuji and the Cherry Blossoms on Asuka Hill , 1929