I have written a lot about the Pre-Raphaelites on this blog over the years and I don’t wish to be repetitive but at the same time there there is always something new to learn and focus your attention on. So, in this post we’ll take a look at John Everett Millais’ early years of married life and the art he created at that time, with a special focus on three beautiful painting “The Blind Girl”, “Autumn Leaves” and “Peace Concluded”, all painted in 1856.

John Everett Millais, The Blind Girl, 1856

John Everett Millais, The Blind Girl, 1856

On 3rd July 1855, twenty-six year old Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais finally married Effie Gray. They were overjoyed about the prospect of finally being together, but also emotionally exhausted after years of dealing with the struggles; for Effie the struggle was her previous unhappy marriage with the Victorian art critic John Ruskin, and for Millais it was the anguish at having to suppress his love for Effie during the time she was still married or just recently divorced. The irony is that it was through John Ruskin that the couple got acquainted in the first place. They did meet once before, on a ball, but it wasn’t a memorable event for either of them. Ruskin was a huge supporter of the Pre-Raphaelites and one of the first critics who praised their style. In 1853, Ruskin proposed that John Millais and his brother William join him and Effie on a holiday in the emerald green wilderness of Scotland.

John Everett Millais, Waterfall or Effie at Glenfinlas, 1853, 11.5″ (29.2 cm) x 15.4″ (39.1 cm)

While there, Millais worked on his painting “The Order of Release” and Effie posed for the female figure. They grew fond of each other’s company and Effie soon started opening up about her life; about her loving parents, childhood spent in Scotland, her siblings, but also about the sad truth of her marriage with Ruskin. Naturally, this was a delicate topic and she must have had great trust in him to share such a thing. Millais as absolutely shocked that Ruskin could be so cold and disinterest in his young beautiful wife, and he was also overwhelmed with a feeling of futility and empathy. He wanted to help Effie but didn’t know quite how, and his own feelings of affection towards her added an even greater torment. In his letters home during that trip he writes of Effie “She is the most delightful unselfish kind-hearted creature I ever knew, it is impossible to help liking her…” And also he started giving her drawing lessons and she proved to be a very dutiful pupil, Millais writes “She has drawn and painted some flowers in oil (the first time she has ever touched a brush) almost as well as I could do them myself.” Millais also painted this charming and very detailed little painting of Effie on the rocks by a waterfall.

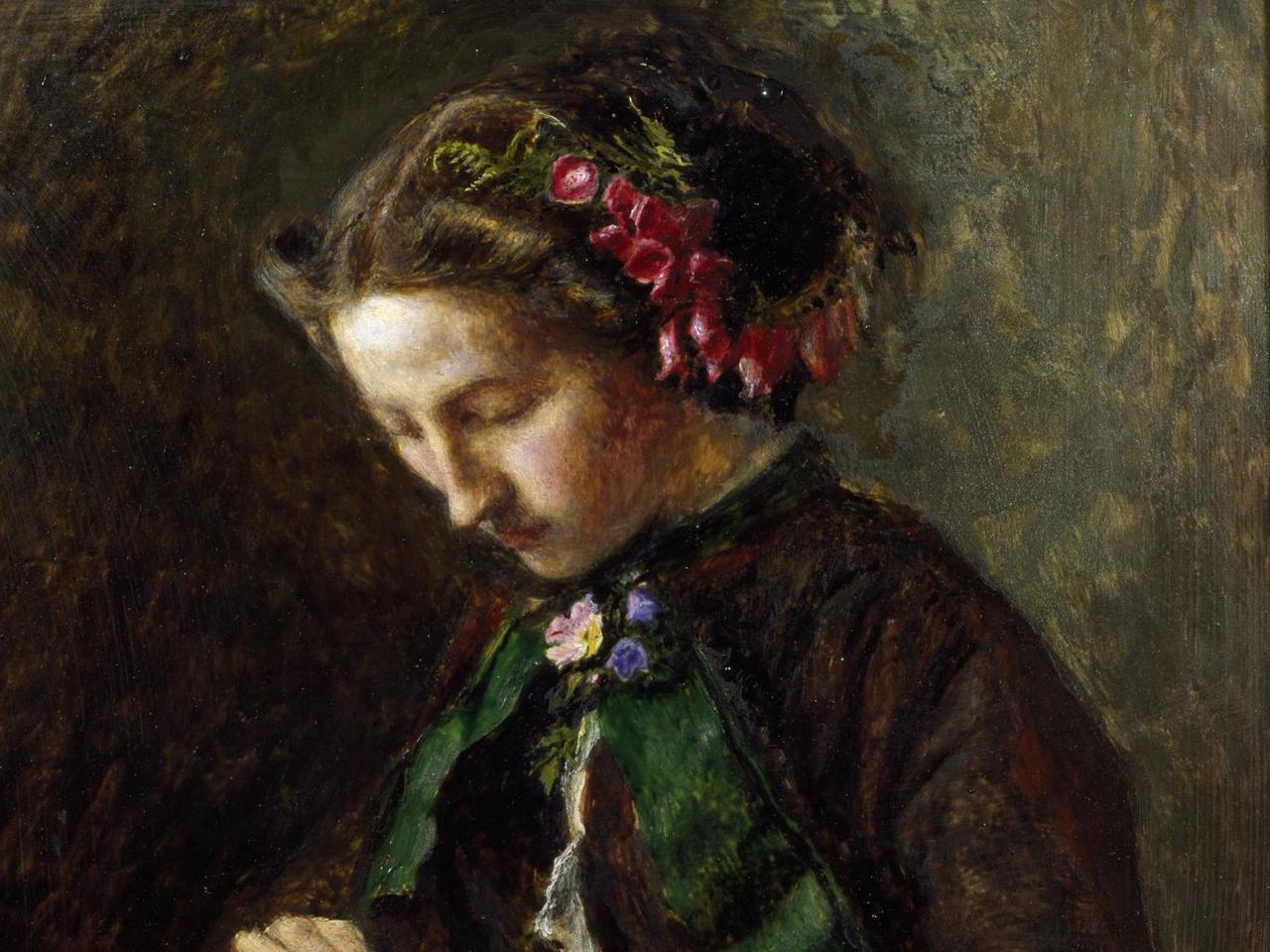

John Everett Millais, A portrait of Effie Gray, 1853

Let’s skip the part about the sad and bitter marriage annulment between Effie and Ruskin and focus on the young newlyweds in the summer of 1855. After the wedding ceremony, they sat in a train and were on their way to spend a five week honeymoon in the west coast of Scotland. Millais was very nervous but Effie cheered him up and they had marvelous time together. Since Effie had horrible experiences with the London life, the couple decided to live in Scotland, near to her parents’ house. The letters both wrote to their families show the joy they experienced, Effie wrote to her mother saying “I am so happy with him. You can imagine how much I appreciate his natural character. (…) he is so kind and nice and easy to be with.” She also wrote to her brother George “He diverts me beyond everything. I don’t think I have laughed so much since I was Alice’s age.” (Alice was ten years old at the time.) As they settled into their home, Effie tried to do everything in her power to make their life revolve around his art. She was very practical and nurturing, and offered both her help and compassion when his painting drove him crazy; she would urge him to take a rest when he was working to hard and was very successful in finding local young girls to pose for him. And if he needed a historical costume for his painting, she would do the research and sew it for him.

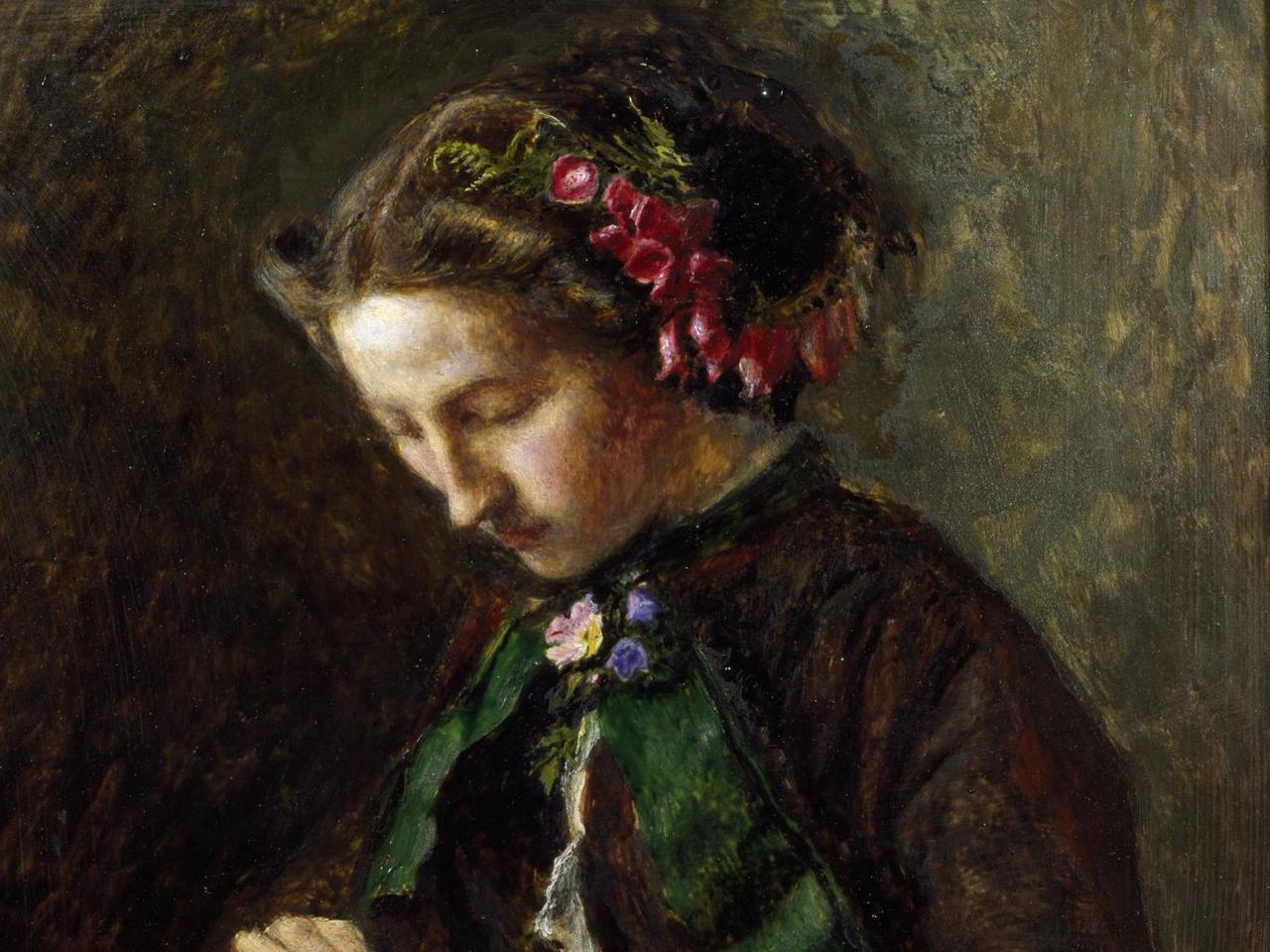

John Everett Millais, Autumn Leaves, 1856

In 1856 Millais had three remarkable paintings to show; “The Blind Girl” where he portrayed two child beggars one of whom is blind, resting after a rainstorm before they continue their journey to another town. The sad fate of the blind girl and their destitute situation is in contrast with the vibrant and warm colours; that overwhelming warm green-yellow of the endless field behind them, the orange of her dress, the coppery orange-red of her cloak and her hair, and even the blue sky in the upper part of the painting seems so warm. It’s very detailed; just look at the grass and the ground in the lower left corner, and all the birds and the animals, the glistening magical rainbow, and the town in the distance. All this beauty of nature around her, but the poor blind girl cannot see it. But she is able to enjoy other sensations; smell of fresh grass and summer’s day, and song of birds.

Another memorable masterpiece is “Autumn Leaves”. I don’t even know how to do justice to the painting’s beauty with my words. I adore the mood and the colours so much, it’s full of feelings and at the same time beautiful and tinged with melancholy and transience, and it so vividly captures the moment, the twilight of the autumn day. The warmth of the colours, the details of the leaves, the faces of young girls, the sensitivity to capturing the atmosphere so well, it’s just stunning and it’s easy to see what all these paintings where a huge success in London in 1856. Despite the bitter feeling of betrayal, Ruskin still managed to be objective when analysing Millais’ art and he praised this picture saying that it is “by much the most poetical work the painter has yet conceived; and also, so far as I know, the first instance of a perfectly painted twilight. It is easy, as it is common, to give obscurity to twilight, but to give the glow withing its darkness is another matter; and though Giorgione might have come nearer glow, he never gave the valley mist. Note also the subtle difference between the purple of the long nearer range of hills and the blue of the distant peak.”

John Everett Millais, Peace Concluded, 1856

The Last picture of the 1856 trio is “Peace Concluded”, also known as “The Return from Crimea” which shows a wounded officer who had recently returned from the war and is now resting in his family nest, surrounded by his loving wife and rose-cheeked children. The foliage behind them looks as if it came from Millais’ painting “Ophelia” while the garish carpet looks like it belongs to the interior from William Holman Hunt’s painting “Awakening Conscience”. A dog curled on the sofa overlooks the scene. Effie Millais posed for the central figure of the wife, and the husband and wife are presented as very close to each other; her arms are wrapped around him comfortingly and this could be related to Millais’ personal life and his joy and closeness with Effie because the date of the picture matched the date of their first year marriage anniversary.

I felt it was important to discuss this short period in Millais’ life because his style changed a lot after he got married; being the man and the bread-winner for an ever growing family (he and Effie ended up having eight children) he was strained by responsibilities and chose to paint with less emphasis on details and focusing on themes that he knew the audience would love and approve, and people would want to buy. Some, like William Morris for example, have commented that he had sold out and that he didn’t stay true to the original aims of the Pre-Raphaelite Brootherhood; he certainly didn’t spent as much time studying nature attentively or painting in a very detailed style like he did early in his career, and he didn’t stay true to the original aim of originality. Still, that’s not to say all his later work is bad, not at all, there are many interesting paintings in his oeuvre but I feel that these paintings from mid 1850s are some of his last Pre-Raphaelite gems.

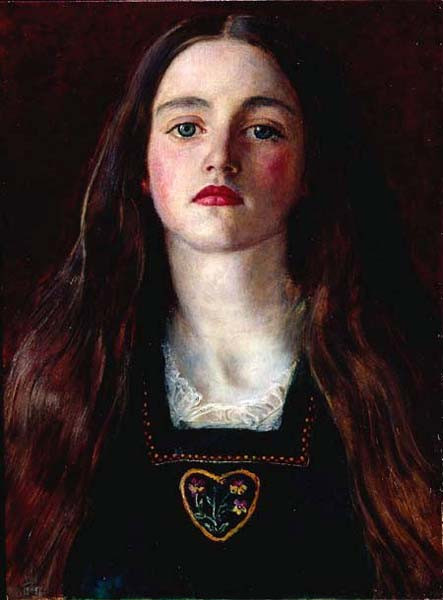

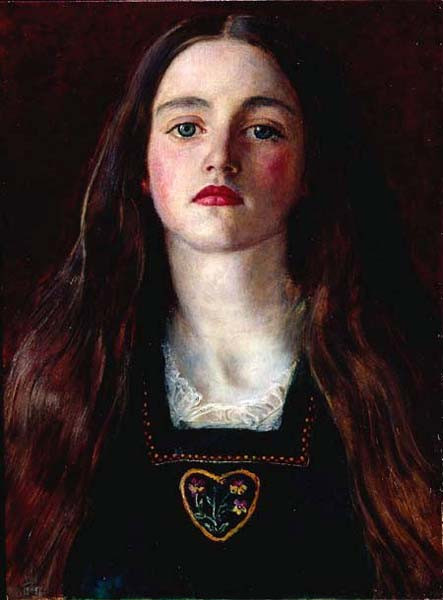

John Everett Millais, Sophie Gray, 1857

John Everett Millais, The Vale of Rest, 1858-59

John Everett Millais, The Martyr of the Solway, 1871

John Everett Millais, Portrait of Alice Gray, 1858

John Everett Millais, Spring (Apple Blossoms), 1859

This is how Millais defended himself in a letter to William Holman Hunt: “You argue that if I paint for the passing fashion of the day my reputation some centuries hence will not be what my powers would secure me if I did more ambitious work. I don’t agree. A painter must work for the taste of his own day. How does he know what people will like two or three hundred years hence? I maintain that a man should hold up the mirror to his own times. I want proof that the people of my day enjoy my work, and how can I get this better than by finding people willing to give me money for my productions, and that I win honours from contemporaries. What good would recognition of my labours hundreds of years hence do me? I should be dead, buried, and crumbled into dust.”

I think it’s fascinating to actually hear an artist make such a statement, and show that he does care about getting praise and approval from his time and people of his time.

Tags: 1850s, 1855., 1856., art, Autumn leaves, Effie Gray, England, John Everett Millais, John Ruskin, married life, Peace Concluded, Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Pre-Raphaelites, Scotland, The Blind Girl, Vivid colours, wedding

Dreamy sky, pic found here.

Dreamy sky, pic found here.