Rossetti’s painting Beata Beatrix, laden with symbolism and imbued with spirituality, can be viewed in two ways: as the ultimate expression of Rossetti’s passionate love for Lizzie, a love that transcends even death, and, as a synthesis of Rossetti’s life-long fascination with Italian poet of the Late Middle Ages – Dante Alighieri.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, Oil on canvas, painted about 1863-70, 86.4 x 66cm, Tate

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, Oil on canvas, painted about 1863-70, 86.4 x 66cm, Tate

Rossetti, who loved Lizzie ardently but not always most faithfully, often made connections between her and Beatrice; Dante’s muse and unrequited love, so much so that is seems Lizzie’s death came as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Her death and this painting erased the border between Rossetti’s own life, love and loss, and that of his idol Dante. Having lost their muses, the two artists, although separated by centuries, were finally spiritually united. Both Rossetti and Dante sought refuge in art because it transcends the short life of us mortals. Ars Longa, Vita Brevis (Art is long, life is short.) – Lizzie’s life was short, her love for Gabriel lasted even shorter, and yet this painting, along with many other, enables us, century and a half later, to feel the same grief that Rossetti felt upon Lizzie’s death.

‘Dante’s Vita Nuova, the subject of Beata Beatrix, was one of numerous early Italian works that Rossetti translated. Dante portrays himself in La Vita Nuova as a poet captivated by an unattainable love personified by Beatrice. After Beatrice’s death Dante, who cannot overcome his lingering love for her, resolves to express his love through his art.‘*

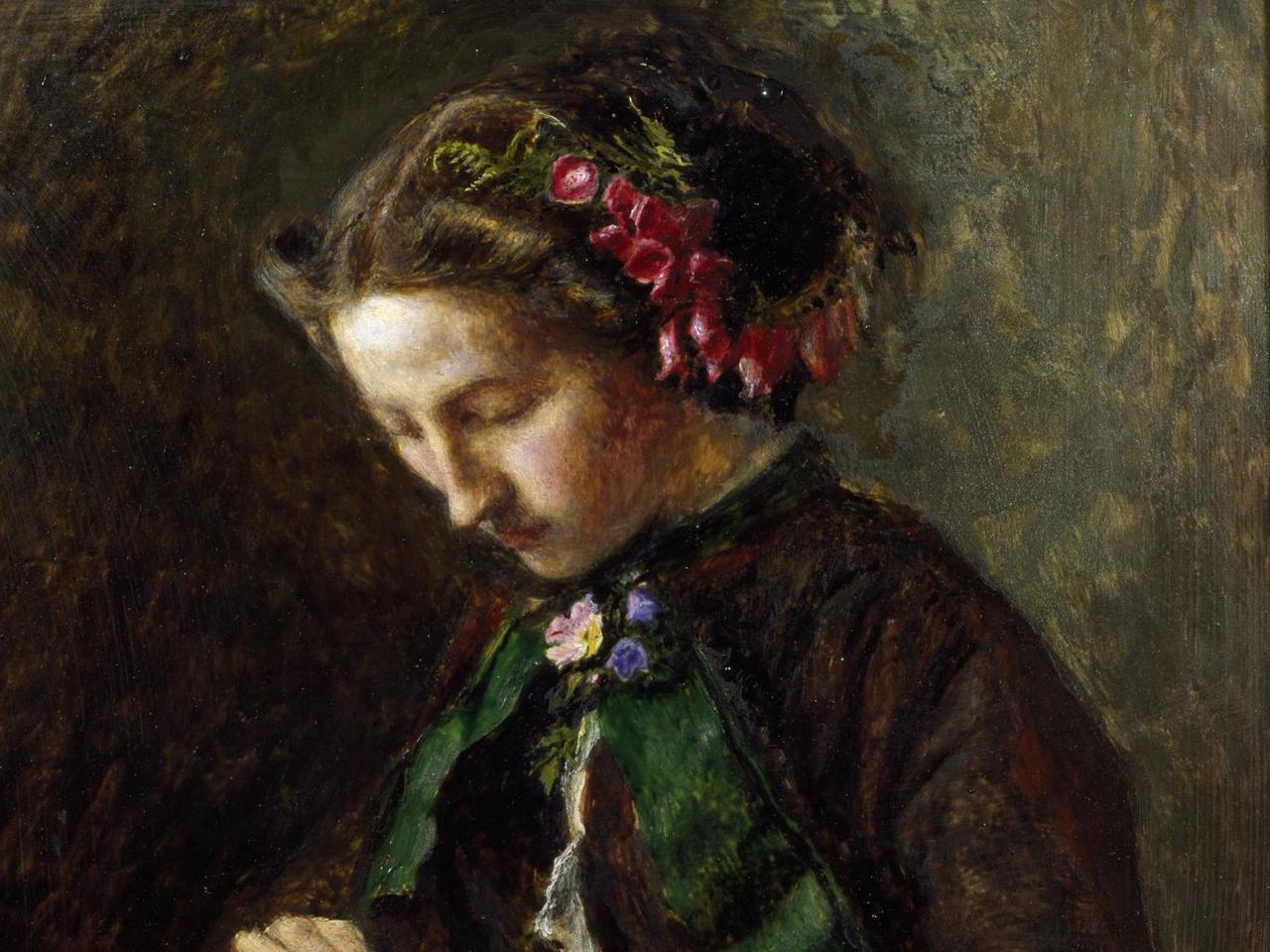

Dante Gabriel Rossetti – Elizabeth Siddal, study for ‘Delia’ in the ‘Return of Tibullus’ (1853)

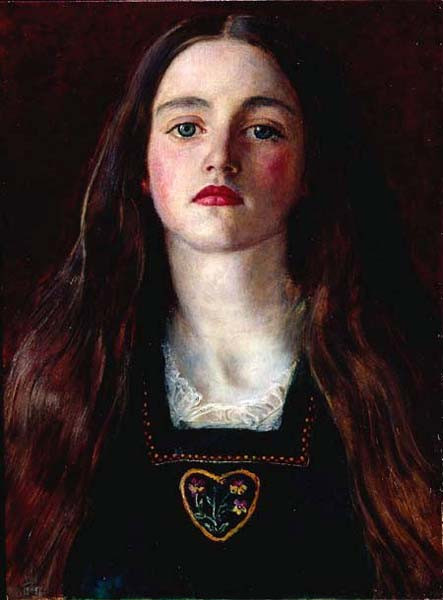

In this painting Lizzie Siddal embodied Dante’s Beatrice. Her head, crowned by exuberant masses of coppery red hair, is tilted back. Her face expression reveals a meditative, contemplative state, perhaps indicating that Beatrice is praying and calmly anticipating her death. She’s wearing a similar, medieval-style dress that can be seen in Rossetti’s painting ‘Beatrice, Meeting Dante at a Wedding Feast, Denies him her Salutation’ from 1855. Also, her face expression bears resemblance to one of Rossetti’s early studies for ‘Delia’ in the ‘Return of Tibullus’.**

Lizzie’s heavy-lidded eyes now closed could be interpreted as a symbol of her transition into the underworld, like Eurydice in Greek mythology. And just like poor, grief-stricken Orpheus, Rossetti was unable to rescue his sweet Lizzie from the eternal sleep. Knowing Lizzie’s addiction to laudanum, one could get the impression that her state is nothing more than an opium dream. Her lips, the same crimson-coloured lips that Rossetti had kissed many times, are slightly parted which brings to mind Rossetti’s poem The Kiss and these verses:

“For lo! even now my lady’s lips did play

With these my lips such consonant interlude

As laurelled Orpheus longed for when he wooed

The half-drawn hungering face with that last lay.”

Other-worldly mood of the scene is absolutely beautiful, and I think that’s the very thing that makes this painting so special. Rossetti spent seven years of his life painting it (1863-1870) and it stands as a barrier between his early years characterised by medieval subjects and infatuation with Lizzie, and the following period when he focused on female sensuality and produced the ‘femme fatale’ paintings that everyone knows and loves.

Two figures emerge from the golden haze in the background: on the left – a figure of angel representing Love, and holding a flame in his hand, symbolising the soul of Beatrice; on the right – a figure of Dante, hopelessly trying to bring Beatrice back to life. Sundial casts its shadow on the number nine; the time of Beatrice’s death on 9th June 1290. For Dante, number nine had a mystical quality because of its connection to Beatrice. Rossetti noted in a letter to Ellen Heaton in 1863:

‘You probably remember the singular way in which Dante dwells on the number nine in connection with Beatrice in the Vita Nuova. He meets her at nine years of age, she dies at nine o’clock on the 9th of June, 1290. All of this is said, and he declares her to have been herself ‘a nine’, that is the perfect number, or symbol of perfection.’*

Behind Dante and the figure of Love we see a vague contours of Florence; the place where Dante’s story was set. We see a red dove carrying a poppy flower into Beatrice’s open hands. All this symbolism, along with the lavishing usage of gold could be interpreted as the beginning of Symbolism. As we know, many artists after Rossetti loved using gold in abundance, whether as a colour or in the form of real leaves of gold; Gustave Moreau and Gustav Klimt to name a few. Such profusion of gold evokes the glory days of Byzantine Empire and its architectural splendours. The spiritual yet luxurious mood of this painting reminds me of the atmosphere in Eastern Orthodox Churches.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ‘Beatrice, Meeting Dante at a Wedding Feast, Denies him her Salutation’ (1855)

In the final episode of ‘Desperate Romantics’ we see the creation of this painting; Rossetti tries to memorise her face and then starts painting furiously. Everyone is saddened by her death. Effie and John, the happy couple in their cosy home, gaze at his study of Lizzie’s face for Ophelia. Hunt is in solemn solitude, praying to god by the candlelight, Fred – alone, drinking and kissing the lock of her coppery-golden hair. Death is so idealised and glamorised as an idea, but very sad when it actually occurs. It’s ironic that some of Rossetti’s best-known and some of the greatest Pre-Raphaelite artworks were painted after Lizzie’s death.

Sadly, death marks both the beginning and the end of Lizzie Siddal’s career as a model. Ten years before her death, in 1852, she posed as Ophelia for Millais, and almost died during the process, and after she died, Rossetti painted Beata Beatrix. (Note: Ophelia is not the first painting she sat for, but it is certainly the best known.) I see this painting as Rossetti’s way of saying ‘Farewell, My Lizzie’. Also, with this painting Rossetti seems to be exploring the connection between death and eroticism, something that would go on to be very popular a subject in decadent society of fin de siecle. Rossetti – always ahead of his time.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) – Portrait of Elizabeth Siddal, ca 1860

I think that despite his selfishness and interest in other women, Rossetti deeply loved Lizzie; she was not just a muse and a lover to him, but a true soulmate. He was obsessed with drawing her when she was alive, he buried his book of poems with her when she died, and I believe that the vision of her coppery hair and heavy-lidded greenish eyes stayed etched in his mind till the end of his life. Lizzie left emptiness when she died, and Rossetti described such feelings in his poem from ‘The House of Life’:

“What of her glass without her? The blank gray

There where the pool is blind of the moon’s face.

Her dress without her? The tossed empty space

Of cloud-rack whence the moon has passed away.

Her paths without her? Day’s appointed sway

Usurped by desolate night. Her pillowed place

Without her? Tears, ah me! for love’s good grace,

And cold forgetfulness of night or day...”

***

Elizabeth Siddal Plaiting her Hair null by Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1828-1882, c. 1850s

The title is obviously a reference to Joy Division, and I chose it because I think it’s relevant to the love affair of Lizzie and Rossetti. No doubt that she was annoyed by his celebration of female sensuality and friendships with prostitutes, and that he often thought living with her brought nothing but restrictions and dullness. And yet, aside from these everyday troubles, Rossetti expressed nothing but pure beauty and adoration in his portrait of Lizzie, and what woman could possibly want more?

***

“When routine bites hard,

And ambitions are low,

And resentment rides high,

But emotions won’t grow,

And we’re changing our ways,

taking different roads.

Then love, love will tear us apart again.

Love, love will tear us apart again.

Why is the bedroom so cold?

You’ve turned away on your side.

Is my timing that flawed?”****

Tags: 1860s, art, Beata Beatrix, Beatrice, Dante Alighieri, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Death, dove, Elizabeth Siddal, gold, Joy Division, laudanum, love, Love Will Tear Us Apart, Painting, poems, Poppy, Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Pre-Raphaelites, Victorian era, Without her

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Venus Verticordia, 1864-68

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Venus Verticordia, 1864-68

Edward Burne-Jones, Le Chant d Amour (Song of Love), 1869-77

Edward Burne-Jones, Le Chant d Amour (Song of Love), 1869-77