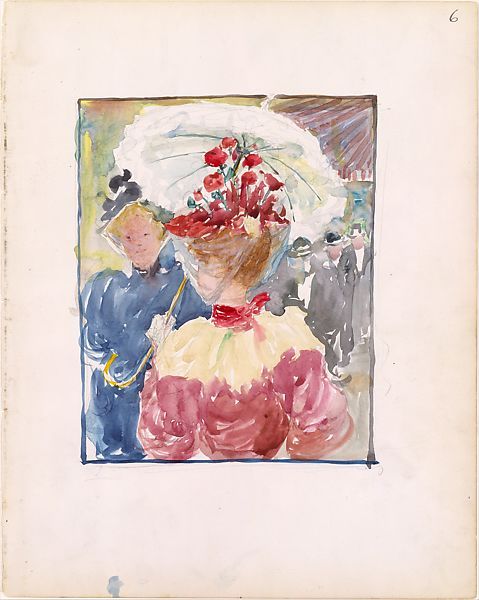

“Hardly had she ended her prayer, when a heavy torpor seizes her limbs; and her soft breasts are covered with a thin bark. Her hair grows into green leaves, her arms into branches; her feet, the moment before so swift, adhere by sluggish roots; a leafy canopy overspreads her features; her elegance alone remains in her.”

John William Waterhouse, Apollo and Daphne, 1908

John William Waterhouse, Apollo and Daphne, 1908

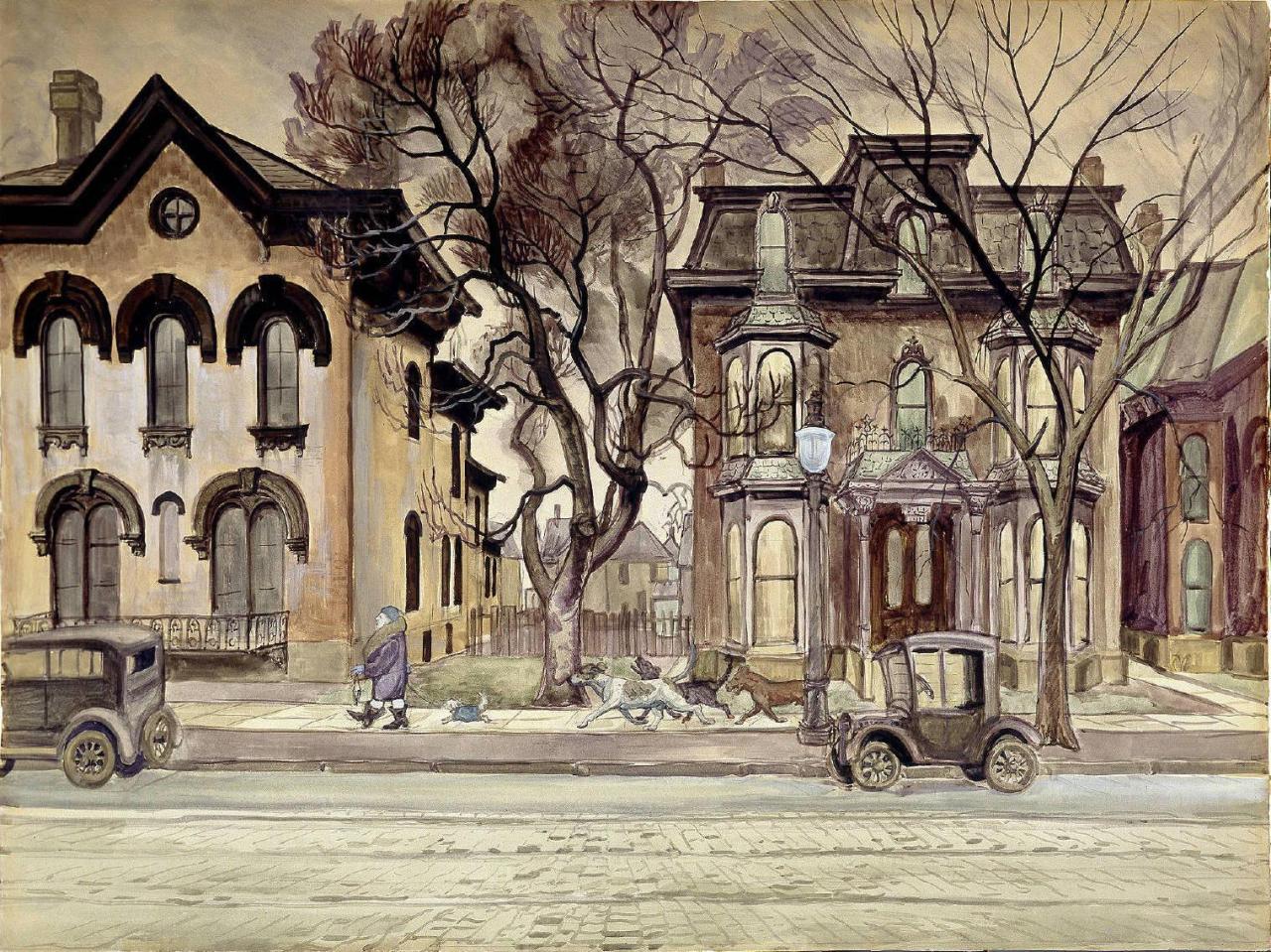

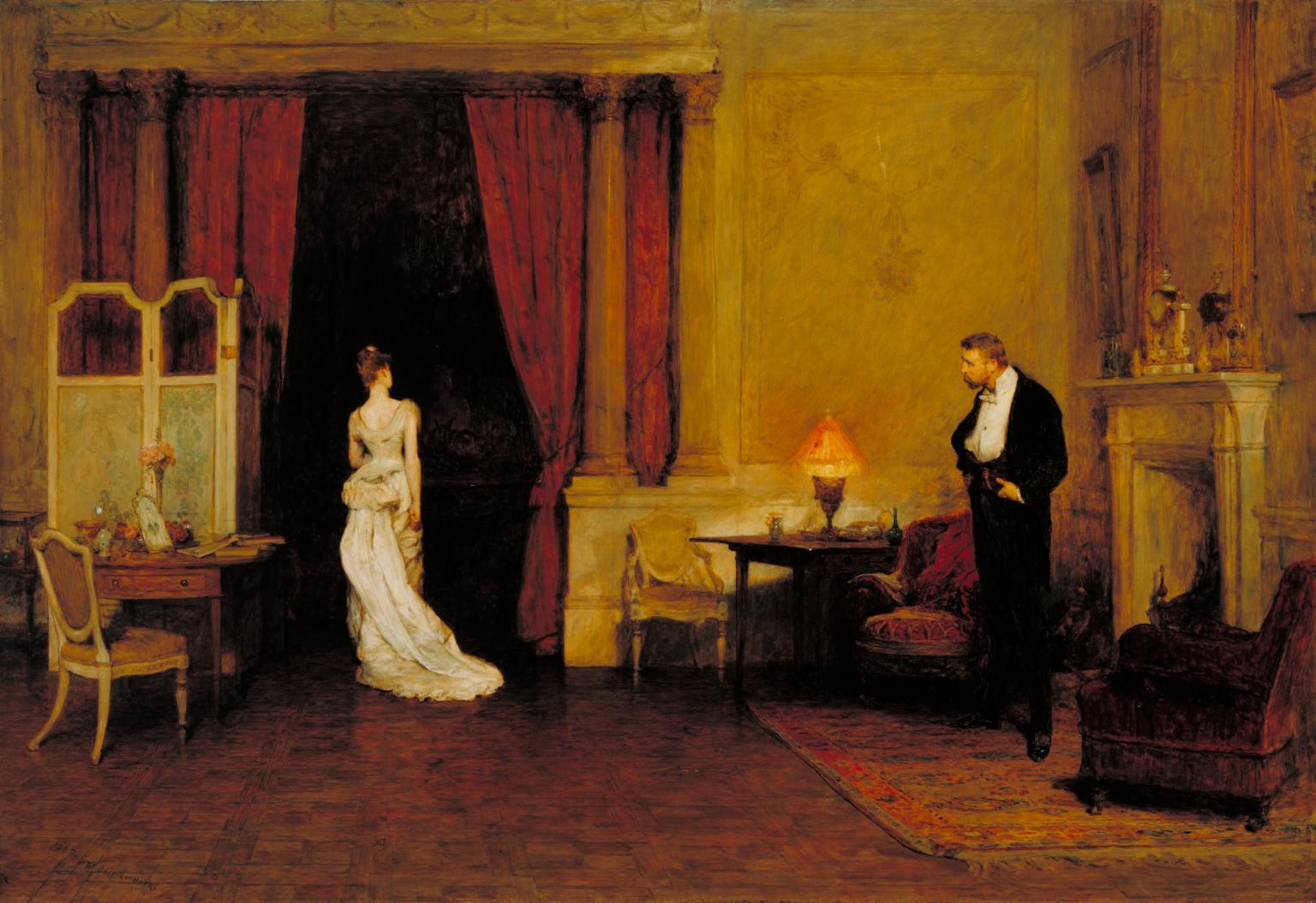

As the title itself suggest, a motif of transformation, of metamorphosis, lingers throughout the tales from the Roman poet Ovid’s narrative poem “Metamorphosis”. Along with the motif of love, of course. A tale of Apollo and Daphne is perhaps the most explored one in the arts because the poem is filled with imagery which is easy to translated into the visual language of painting and sculpture. Bernini’s beautiful sculpture certainly comes to mind, along with many Renaissance paintings, but when I think of mythology scenes in art, I think of the prolific, imaginative, well-known and well-loved British painter born in Rome; John William Waterhouse. I am not saying that his version is the best, but it is the first one that came to my mind because I am a fan of his dreamy paintings woven with romanticism and filed with intricate details and vibrant colours. His art is always so beautiful, there is no other word for it. The tale of Apollo and Daphne is that of pursuit and lust. Daphne is an athletic, free-spirited virgin just like Diana, and she isn’t the one who falls in love easily, but she is very beautiful and Apollo simply cannot contain himself. Here is a passage from Ovid’s Metamorphoses which describes Daphne’s personality. I really love her rebellious, independent nature:

“Many a one courted her; she hated all wooers; not able to endure, and quite unacquainted with man, she traverses the solitary parts of the woods, and she cares not what Hymen, what love, or what marriage means. Many a time did her father say, “My daughter, thou owest me a son-in-law;” many a time did her father say, “My daughter, thou owest me grandchildren.” She, utterly abhorring the nuptial torch, as though a crime, has her beauteous face covered with the blush of modesty; and clinging to her father’s neck, with caressing arms, she says, “Allow me, my dearest father, to enjoy perpetual virginity; her father, in times, bygone, granted this to Diana.” (read the entire tale here)

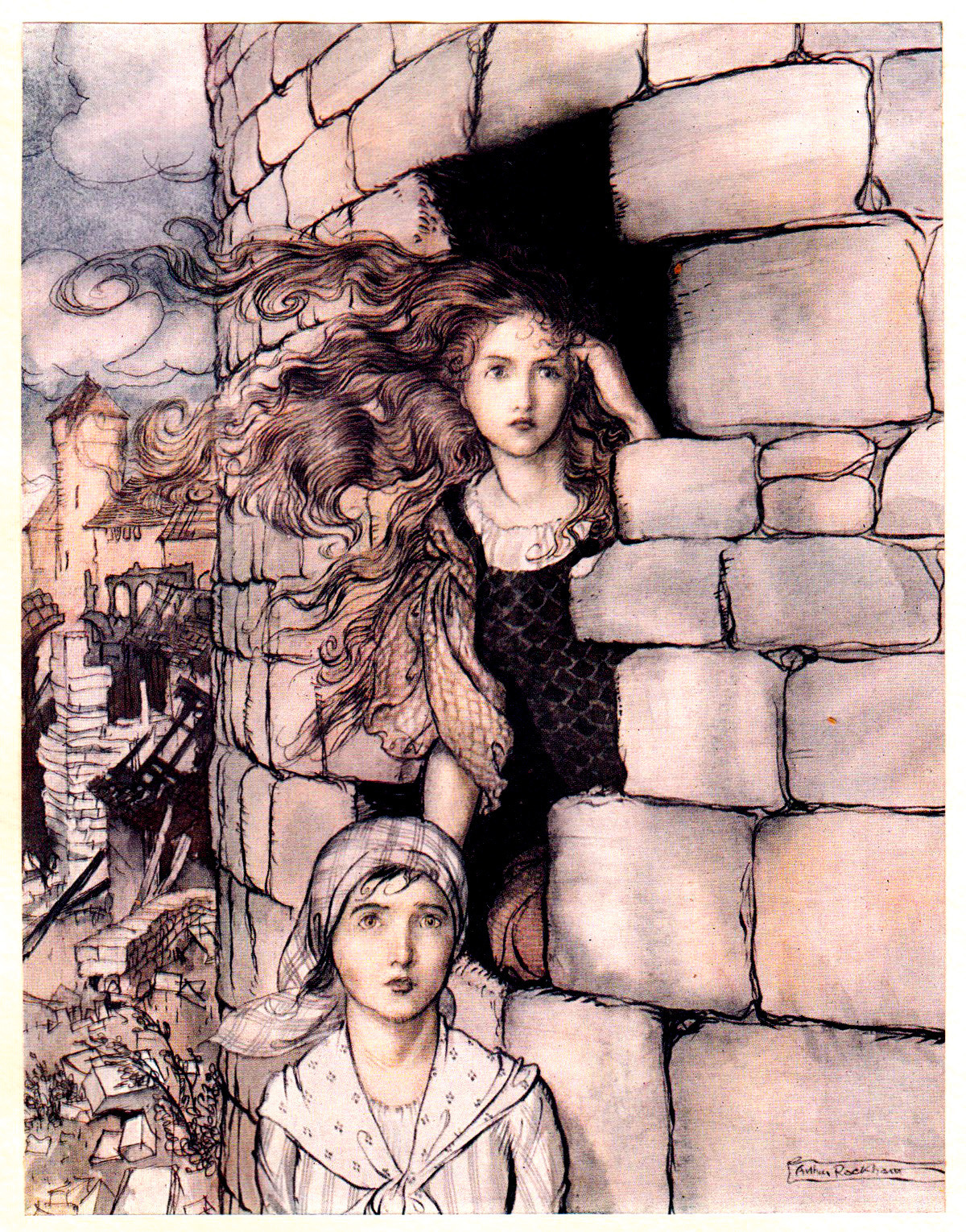

Bernini, Apollo and Daphne, 1622-25. Picture found here.

Led by the most primal urges, Apollo, the God of Lightness and Clarity, chases the beautiful, free-spirited and wild nymph Daphne through the forest. He is holding a lyre in his hand in Waterhouse’s painting, perhaps wooing Daphne with his mellifluous music, but to no avail, for she is determined to remain free and untouched. The painting depicts the moment of climax in the story; the moment when Daphne, having had cried out for help to her father Peneus, is being transformed into a laurel tree. Notice how sensually the soft blue fabric is wrapped around her, and how she is covering her bosom with her arm and with the fabric. Her gaze shows her fear, and Apollo’s hand is stretched because he greedily desires to touch her soft pale skin before it turns to bark:

“Yet he that follows, aided by the wings of love, is the swifter, and denies her any rest; and is now just at her back as she flies, and is breathing upon her hair scattered upon her neck. Her strength being now spent, she grows pale, and being quite faint, with the fatigue of so swift a flight, looking upon the waters of Peneus, she says, “Give me, my father, thy aid, if you rivers have divine power. Oh Earth, either yawn to swallow me, or by changing it, destroy that form, by which I have pleased too much, and which causes me to be injured.”

Hardly had she ended her prayer, when a heavy torpor seizes her limbs; and her soft breasts are covered with a thin bark. Her hair grows into green leaves, her arms into branches; her feet, the moment before so swift, adhere by sluggish roots; a leafy canopy overspreads her features; her elegance alone remains in her. This, too, Phœbus admires, and placing his right hand upon the stock, he perceives that the breast still throbs beneath the new bark; and then, embracing the branches as though limbs in his arms, he gives kisses to the wood, and yet the wood shrinks from his kisses.”

Even though the poor nymph Daphne had transformed into a laurel tree just to escape his lustful embrace, Apollo still doesn’t give up and kisses the tree bark where her skin used to be and promises to celebrate the laurel tree from that moment on:

“To her the God said: “But since thou canst not be my wife, at least thou shalt be my tree; my hair, my lyre, my quiver shall always have thee, oh laurel! Thou shalt be presented to the Latian chieftains, when the joyous voice of the soldiers shall sing the song of triumph, and the long procession shall resort to the Capitol.“

Tags: 1908, Apollo, Apollo and Daphne, art, British artist, chase, Daphne, Greek mythology, John William Waterhouse, laurel, love, lust, Metamorphosis, mythology, Ovid, painter, Painting, Roman mythology

Picture found here.

Picture found here.