“O, woe is me, To have seen what I have seen, see what I see!”

( Hamlet)

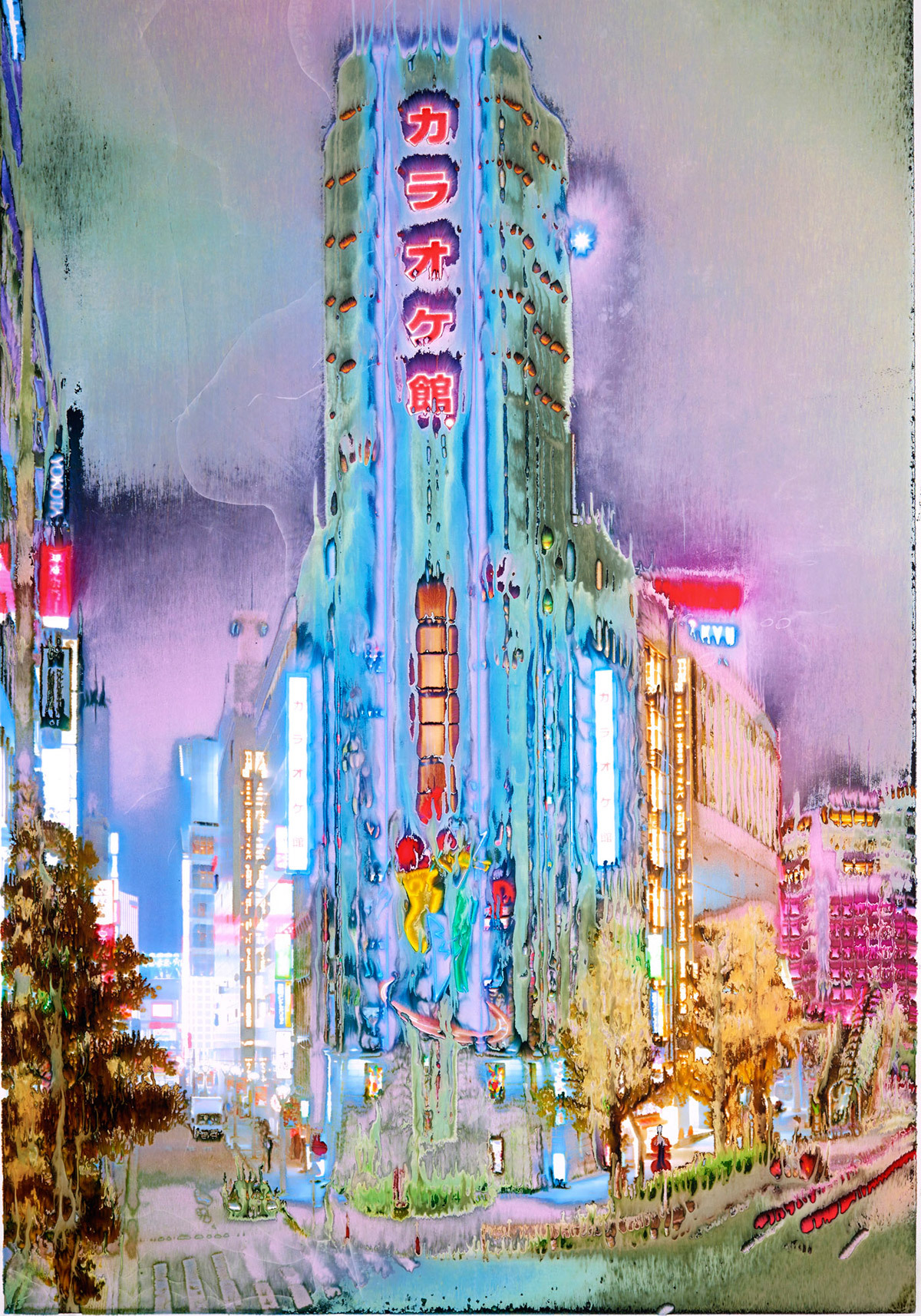

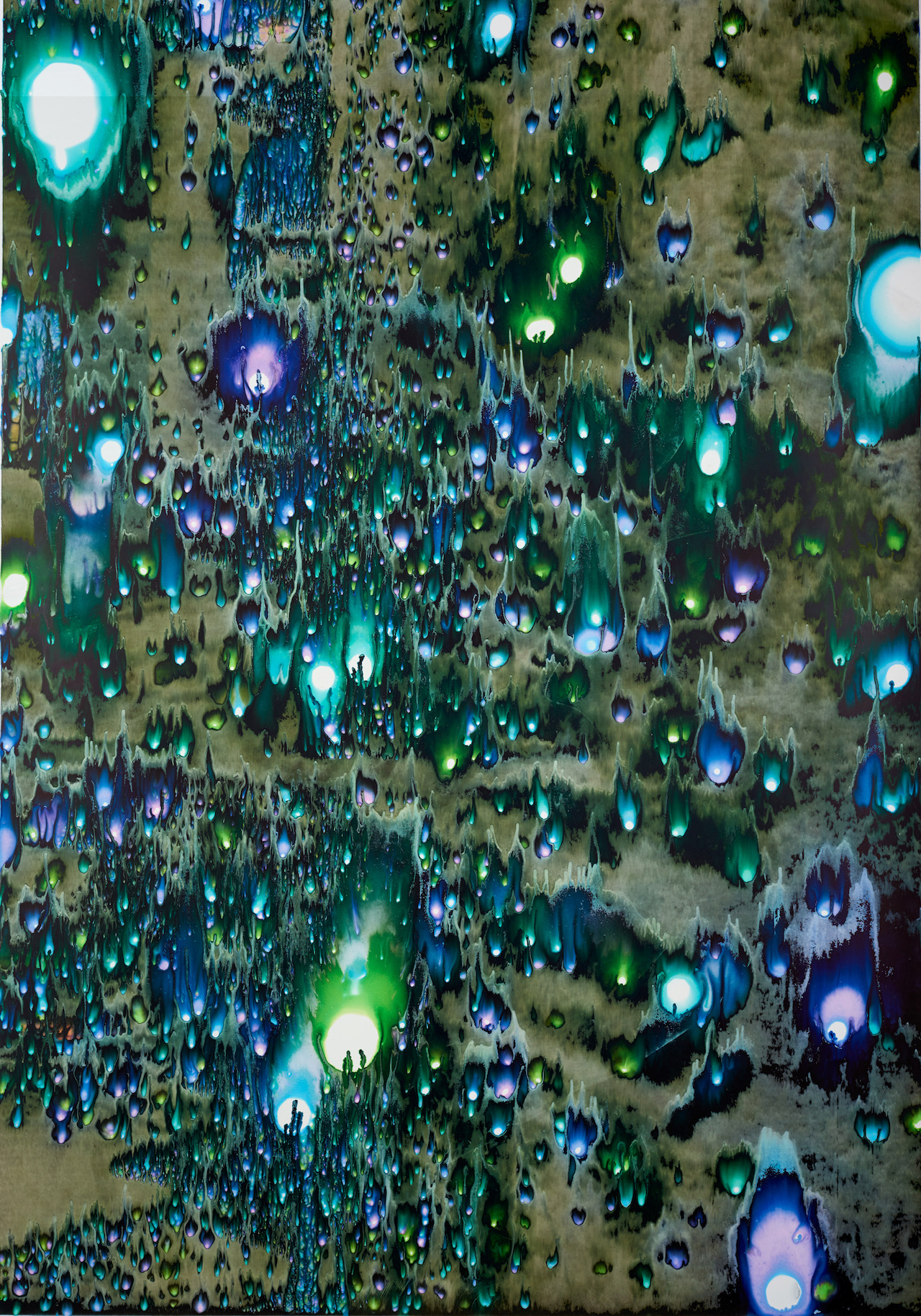

Tom Hunter, The Way Home, 2000

Tom Hunter, The Way Home, 2000

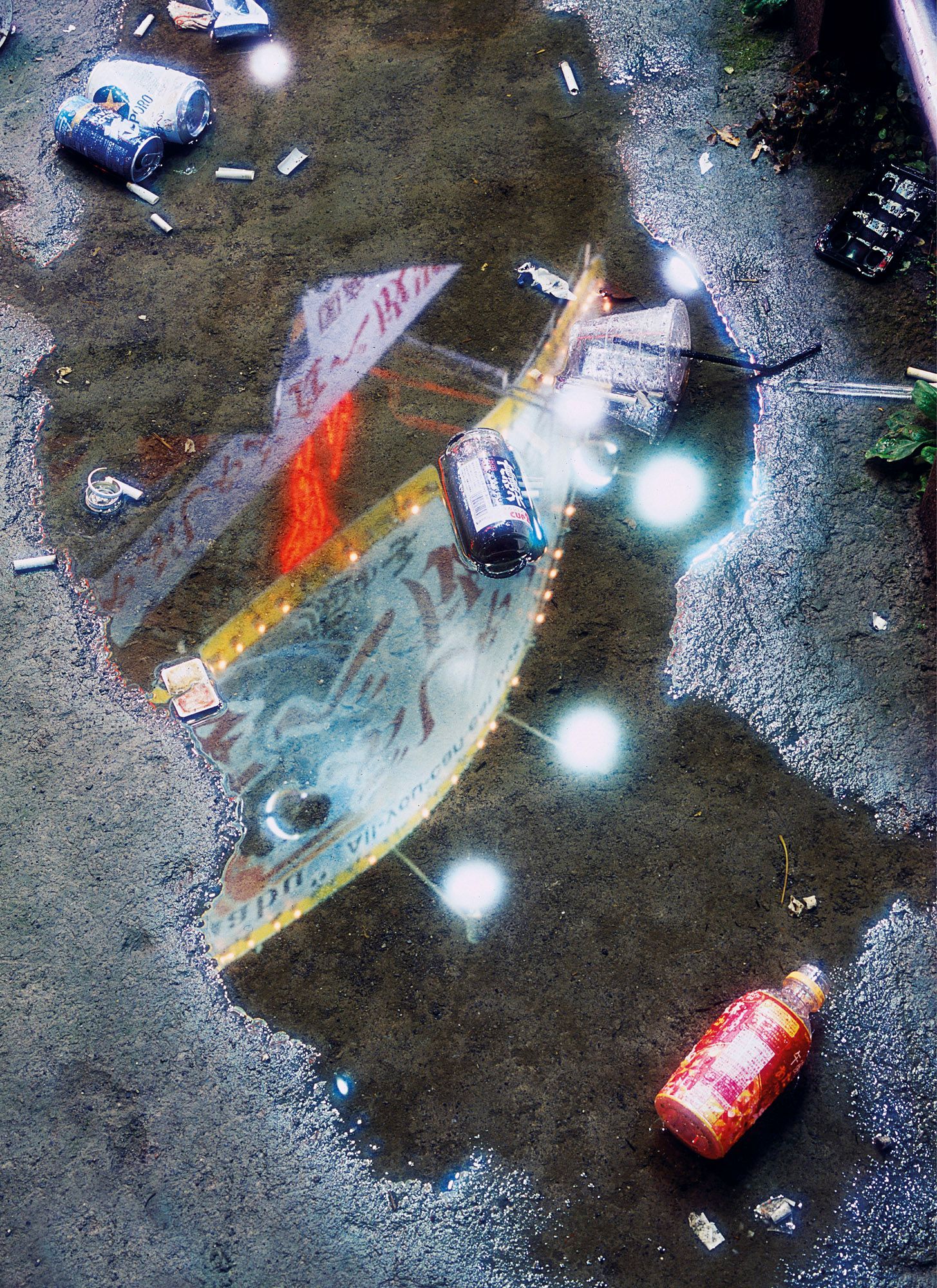

John Everett Millais’ painting “Ophelia” is a beautiful Pre-Raphaelite painting, perhaps even the most beautiful painting that Millais has painted, but it is also a haunting image that keeps inspiring artists even nowadays. It is a blueprint of sorts that allows for further interpretations and reworkings of a seemingly simple theme; a girl drowning. The scene of Millais’ Ophelia drowning slowly with her gown spread out wide amid the enchanting greenery is unbearably dreamy, but the intricate details of natural elements such as grass, flowers and trees betray the Pre-Raphaelites’ philosophy of portraying nature with honesty. Millais painted Ophelia along the banks of the Hogsmill River in Surrey, near Tolworth, Greater London. Nature surrounding Ophelia in Hunter’s photograph is similarly intricate and it allows the eye to observe and indulge in all the details, but the background is not an idyllic English countryside with flowers and butterflies but instead an abandoned urban area, a “dark slippery, industrial motorway of a bygone era”. Nature is claiming back what is rightfully hers. The model for Millais’ Ophelia was Elizabeth Siddal, a moody redhead, the muse and lover of a fellow Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Hunter’s Ophelia is a nameless, pale and rosy-lipped party girl coming home after a night out. Whereas Miss Sidall was trippin’ on laudanum, Hunter’s Ophelia must be coming down from an ecstasy trip. Millais’ Ophelia is beautifully dressed in a soft, silvery tulle gown which looks as if it could have been made from silver dandelion seeds and moonlight. On the other hand, Hunter’s Ophelia is a modern gal and there is nothing romantic about her black shirt and baggy dark blue cargo trousers which are spreading out on the water surface in the similiar way in which the dress of Millais’ Ophelia is spreading out as she is drowning slowly.

The photographs is only a fragment of a series of photographs called “Life and Death in Hackney” taken by Tom Hunter from 1991 to 2001. All the photographs depict a scene from contemporary life but bear resemblance to one or another Pre-Raphaelite painting. Here is an explanation of the series from the artist’s page:

“Life and Death in Hackney’ paints a landscape, creating a melancholic beauty out of the post-industrial decay where the wild buddleia and sub-cultural inhabitants took root and bloomed. This maligned and somewhat abandoned area became the epicentre of the new warehouse rave scene of the early 90’s. During this time the old print factories, warehouses and workshops became the playground of a disenchanted generation, taking the DIY culture from the free festival scene and adapting it to the urban wastelands. This Venice of the East End, with its canals, rivers and waterways, made a labyrinth of pleasure gardens and pavilions in which thousands of explorers travelled through a heady mixture of music and drug induced trances.

All the images draw upon these influences combining the beauty and the degradation with everyday tales of abandonment and loss to music and hedonism. The reworking of John Millais’s ‘Ophelia’ shows a young girl whose journey home from one such rave was curtailed by falling into the canal and losing herself to the dark slippery, industrial motorway of a bygone era.”

John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1851