“They’re all the same, but each one is different from every other one. You’ve got your bright mornings; your fog mornings; you’ve got your summer light and your autumn light; you’ve got your week days and your weekends; you’ve got your people in overcoats and galoshes and you’ve got your ;people in t-shirts and shorts. Sometimes same people, sometimes different ones. Sometimes different ones become the same, and the same ones disappear. The earth revolves around the sun and every day the light from the sun hits the earth from a different angle.”

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1922

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1922

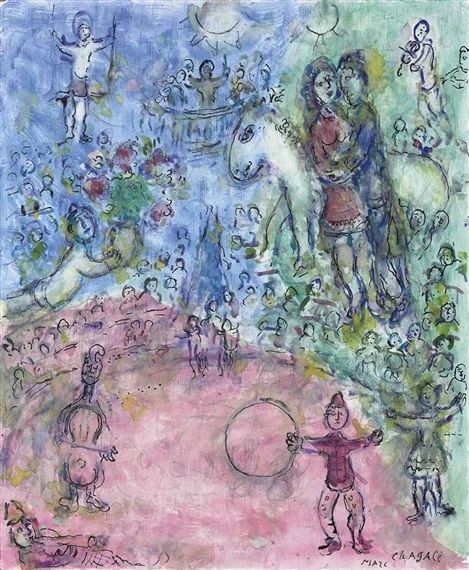

In 1883 Monet had left the bustle of Paris and moved to the village of Giverny where he spent decades, all until his death in 1926, creating, planting, growing and portraying his wonderful garden. As an Impressionist Monet was concerned with painting that what is changeable; the different effects of weather, the dawn and the dusk, the seasons, the wind, the sunshine, the snow and the rain, painting the same motif and exloring it under all these various circumstances. Monet had studies many motifs under different influences and has creates many series of paintings, stacks of hay, poplars, the cathedral, to name a few, but my favourite of his series and perhaps the most fitting for these spring days is his series of water lilies that were blooming in a pond in his estate in Giverny. Monet painted about two-hundred and fifty paintings of water lilies alone. Now that is a dedication indeed. And I really see how that may be possible, I mean, just gaze at these painting and see how beautiful and seductive the water lilies are. The blues and greens of these paintings are soothing for the soul. All of these water lily paintings are very similar, all painted in blues and greens with white or pink for the lotus flower, but at the same time they are all different one from another, all unique and special. Interestingly, the pond with the water lilies takes up the entire space of the canvas, there is no space left for the sky or the clouds. And when are also immersed in this water lily world by gazing at them.

Claude Monet, Nympheas, 1915

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1916

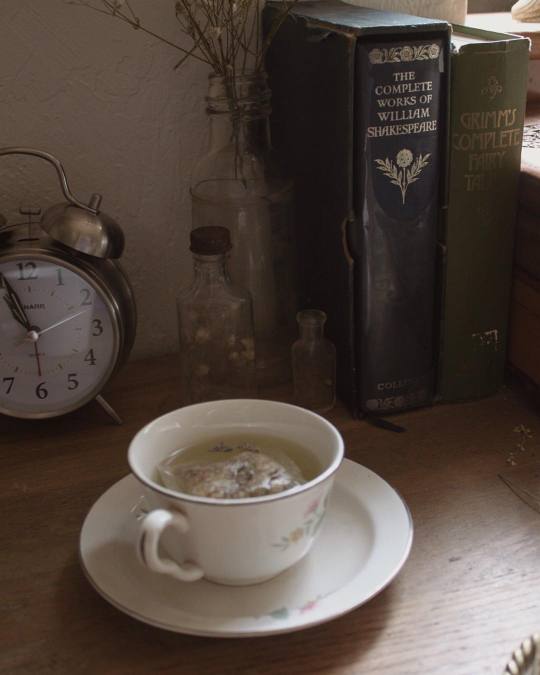

In the eighth episode of the first season of the show “Disenchantment”, which I love, a hermit called Malfus who lives in cave and who took an immortality potion says: “When life is endless, so is everything else! The monotony! The repetition! The monotony! The repetition! The monotony!…” Point taken. As hillarious as his moaning and complaning about immortality is, there is some wisdom to his claims. Without a sense of impermanance to our lives, from whence would a sense of magic arise? The clock of our lives is always ticking off our minutes and we don’t know when it will stop thicking. When you look at life from this perspective everything becomes more precious and you realise that indeed “every day the light from the sun hits the earth from a different angle.”

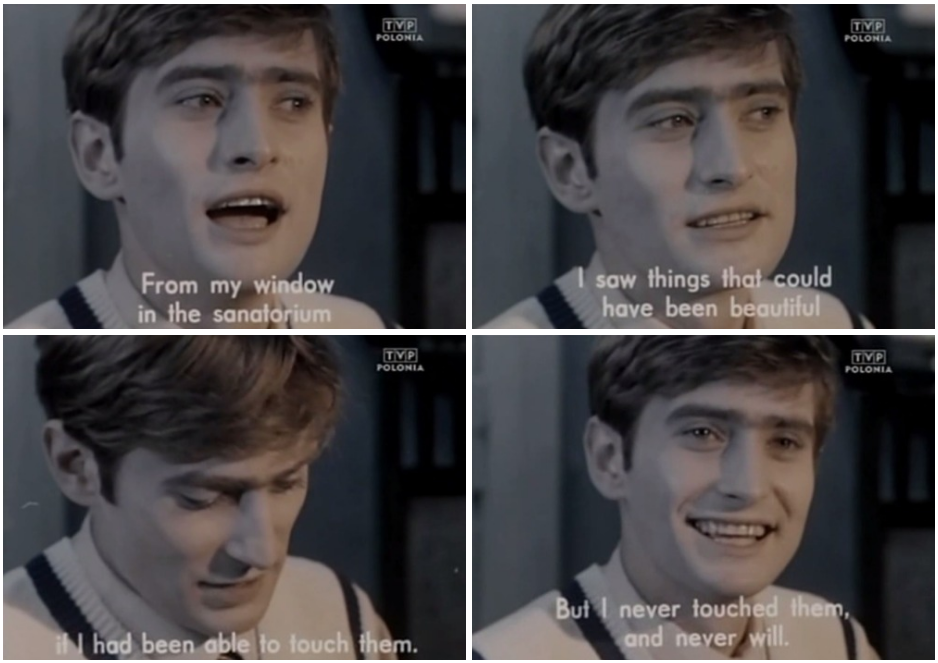

In the film “Smoke” (1995) the life of multiple characters revolve around the same tobacco shop, ran by Auggie Wren (played by Harvey Keitel), which they all frequent, not for the cigarettes alone but also for Auggie’s wisdom and advice. The life of Auggie Wren, who just runs a Brooklyn tobacco shop, may seem totally mundane and uneventful at first glance, but even in this banality of the day to day life, this ‘monotony and repetition’ of days suceeding one another, being all the ‘same’, Auggie manages to find some strange urban beauty. And here you can see a clip from the film where he is showing his photo album to one of his customers, a writer called Benjamin. At first Benjamin is flipping through it uninterested, not understanding the concept, but Auggie tells him: “You’ll never get it unless you slow down, my friend”, urging him to be patient in order to grasp the rhythm and meaning of the pictures, which all show the same view from the street corner of Auggie’s shop, and are all taken at 8 am every morning.

Auggie’s pictures of the street corner, and the last picture is of Auggie himself, all clips from the film.

This is how their dialogue goes:

Benjamin: They’re all the same.

Auggie: That’s right. More than four thousand pictures of the corner of Third Street and Seventh Avenue at eight o’clock in the morning, four thousand straight days in all kinds of weather. That’s why I can never take a vacation. I got to be in my spot every morning at the same time … every morning in the same spot at the same time.

Benjamin: I’ve never seen anything like this.

Auggie: It’s my project. What you’d call: my life’s work.

Benjamin: Amazing. I’m not sure I get it though… What was it that gave you the idea to do this… project?

Auggie: I don’t know. It just came to me. It’s my corner after all. I mean, it’s just one little part of the world but things take place there too just like everywhere else. It’s a record of my little spot.

Benjamin: It’s kinda overwhelming.

Auggie: You’ll never get it unless you slow down, my friend.

Benjamin: What do you mean?

Auggie: I mean, you’re going too fast, you’re hardly even looking at the pictures.

Benjamin: They’re all the same.

Auggie: They’re all the same, but each one is different from every other one. You’ve got your bright mornings; your fog mornings; you’ve got your summer light and your autumn light; you’ve got your week days and your weekends; you’ve got your people in overcoats and galoshes and you’ve got your; people in t-shirts and shorts. Sometimes same people, sometimes different ones. Sometimes different ones become the same, and the same ones disappear. The earth revolves around the sun and every day the light from the sun hits the earth from a different angle.

Benjamin: Slow down, huh?

Auggie: That’s what I recommend. You know how it is. Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow. Time creeps in its petty pace.

Claude Monet, Water lilies, 1915

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1916-19

What better way to show your love and appreciation for something than to give it focus, give it time? Auggie Wren loved the city he lived in and in particular his neighbourhood of Brooklyn, and likewise Monet loved his gardens and especially his delicate and dazzling water lilies. Is it monotony to painting something beautiful for the two-hundredth time, to capture the mundane for the five-hunredth time?

Claude Monet, Water-Lilies, Reflection of a Weeping Willow, 1916-1919

Tags: art, art blog, Auggie Wren, Brooklyn, Claude Monet, day to day life, Film, garden, impermanance, Monet, New York City, Painting, Photography, repetition, series of painting, Smoke (1995), tobacco shop, water lilies

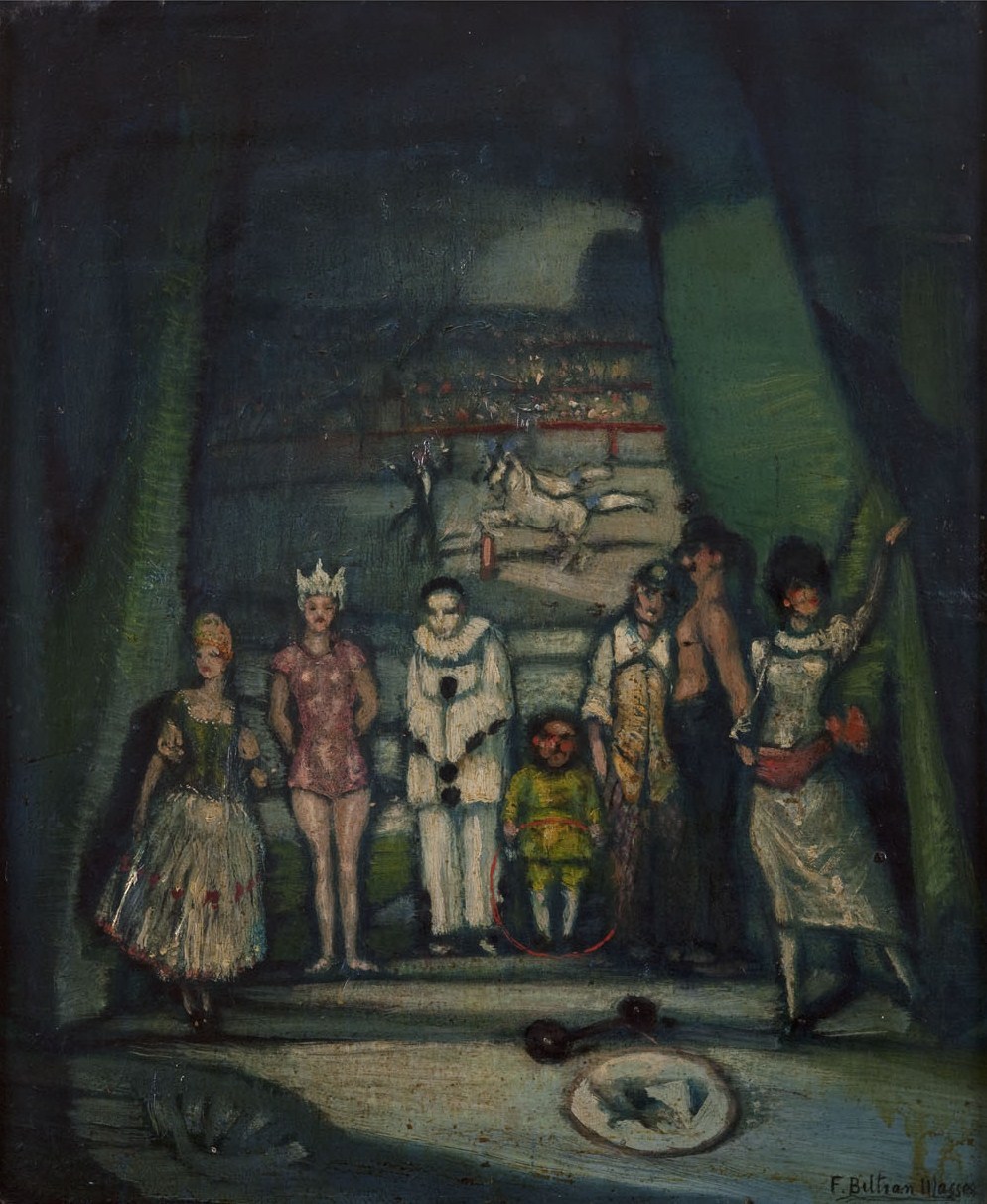

George Barbier, A Renaissance Fair, c 1929

George Barbier, A Renaissance Fair, c 1929

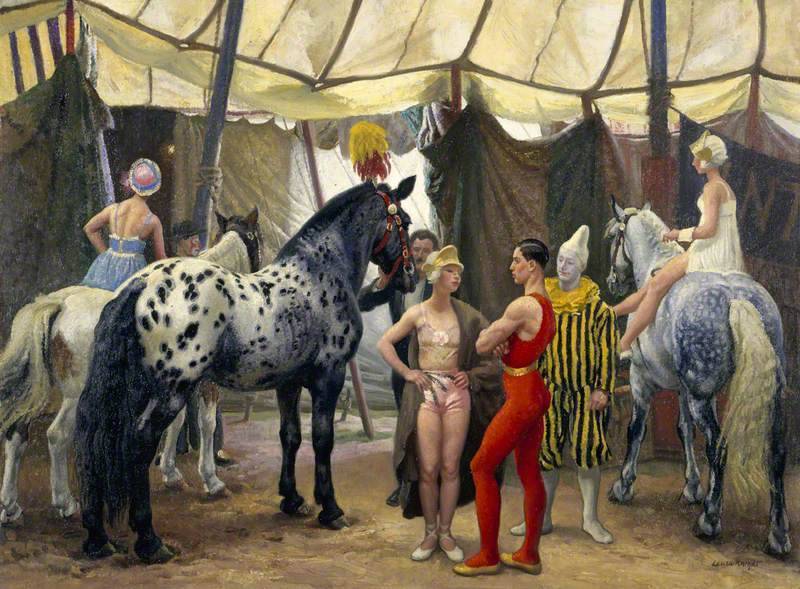

Laura Knight, The Fair, 1919

Laura Knight, The Fair, 1919