German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich was born on this day in 1774 in Greifswald, a town on the Baltic coast whose misty port and lonely ships Friedrich had portrayed in some of his paintings. In August this year I read Rollo May’s wonderful book “Man’s Search for Himself” (published in 1953) and I really enjoyed the chapter on nature and man’s relation to nature, that is, how modern man has lost his connection to the nature and therefore doesn’t feel its charms any more. It’s fascinating how Rollo May writes of man’s alienation, loneliness, emptiness and anxiety in 1953 and I always imagine “modern” man now suffers from all those things, that people in the past were calmer and happier… When May talks of the grandeur and the sublime beauty of nature, I instantly had Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings in mind, I cannot think of another painter who captured the sublime beauty of nature and its relation to men in a more captivating, dreamy and beautiful way. In Friedrich’s paintings the man is always but a small, figure, often with his back turned against us, no face seen, a small, meaningless and transient anonymous figure compared to strong, resilient and lasting nature, whether it’s the sea waves that swallow everything they desire, the cliffs and mountains, the vast spaces where man can ponder, contemplate and perhaps find himself. The following are interesting passage from the chapter called “Little We See in Nature That is Ours”:

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1811

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1811

“Or if one gives himself to the feeling of the distance of the far mountain peaks, permits himself to “empathize” with their heights and depths, and if one is aware at the same moment that the mountain “never was the friend of one, nor promised what it could not give,” and that one could be dashed to pieces on the stone floor at the foot of the peak without his extinction as a person making the slightest difference to the walls of granite, one is afraid. This is the profound threat of “nothingness,” or “nonbeing,” which one experiences when he fully confronts his relation with inorganic being.

People who have lost the sense of their identity as selves also tend to lose their sense of relatedness to nature. They lose not only their experience of organic connection with inanimate nature, such as trees and mountains, but they also lose some of their capacity to feel empathy for animate nature, that is animals. In psychotherapy, persons who feel empty are often sufficiently aware of what a vital response to nature might be to know what they are missing. They may remark, regretfully, that though others are moved by a sunset, they themselves are left relatively cold; and though others may find the ocean majestic and awesome, they themselves, standing on rocks at the seashore, don’t feel much of anything. Our relation to nature tends to be destroyed not only by our emptiness, but also by our anxiety.

A little girl coming home from school after a lecture on how to defend one’s self against the atom bomb, asked her parent, “Mother, can’t we move someplace where there isn’t any sky?” Fortunately this child’s terrifying but revealing question is an allegory more than an illustration, but it well symbolizes how anxiety makes us withdraw from nature. Modern man, so afraid of the bombs he has built, must cower from the sky and hide in caves—must cower from the sky which is classically the symbol of vastness, imagination, release. On a more everyday level, our point is simply that when a person feels himself inwardly empty, as is the case with so many modern people, he experiences nature around him also as empty, dried up, dead. The two experiences of emptiness are two sides of the same state of impoverished relation to life.

Caspar David Friedrich, Moonrise over the Sea, 1822

Near the beginning of the nineteenth century William Wordsworth, among others, clearly saw this loss of the feeling for nature, and he saw the overemphasis on commercialism which was partly its cause and the emptiness which would be its result. He described what was occurring in his familiar sonnet:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers:

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon,

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gather’d now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.—Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

It is not by poetic accident that Wordsworth yearns for such mythological creatures as Proteus and Triton. These figures are personifications of aspects of nature—Proteus, the god who keeps changing his shape and form, is a symbol for the sea which is eternally transforming its movement and its color. Triton is the god whose horn is the sea shell, and his music is the echoing hum one hears in the large shells on the shore. Proteus and Triton are examples of precisely what we have lost—namely the capacity to see ourselves and our moods in nature, to relate to nature as a broad and rich dimension of our own experience.

Caspar Wolf, The Lower Grindelwald Glacier with the Lutschine Stream and the Mettenberg, 1774-77

Descartes’ dichotomy had given modern man a philosophical basis for getting rid of the belief in witches, and this contributed considerably to the actual overcoming of witchcraft in the eighteenth century. Everyone would agree that this was a great gain. But we likewise got rid of the fairies, elves, trolls, and all of the demicreatures of the woods and earth. It is generally assumed that this, too, was a gain since it helped sweep man’s mind clean of “superstition” and “magic.” But I believe this is an error. Actually what we did in getting rid of the fairies and the elves and their ilk was to impoverish our lives; and impoverishment is not the lasting way to clear men’s minds of superstition. There is a sound truth in the old parable of the man who swept the evil spirit out of his house, but the spirit, noticing that the house stood clean and vacant, returned bringing seven more evil spirits with him; and the second state of the man was worse than the first. For it is the empty and vacant people who seize on the new and more destructive forms of our latter-day superstitions, such as beliefs in the totalitarian mythologies, engrams, miracles like the day the sun stood still, and so on. Our world has become disenchanted; and it leaves us not only out of tune with nature but with ourselves as well.

Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea, 1808-10

As human beings we have our roots in nature, not simply because of the fact that the chemistry of our bodies is of essentially the same elements as the air or dirt or grass. In a multitude of other ways we participate in nature—the rhythm of the change of seasons or of night and day, for example, is reflected in the rhythm of our bodies, of hunger and fulfillment, of sleep and wakefulness, of sexual desire and gratification, and in countless other ways. Proteus can be a personification of the changes in the sea because he symbolizes what we and the sea share— changing moods, variety, capriciousness, and adaptability. In this sense, when we relate to nature we are but putting our roots back into their native soil.

But in another respect man is very different from the rest of nature. He possesses consciousness of himself; his sense of personal identity distinguishes him from the rest of the living or nonliving things. And nature cares not a fig for man’s personal identity. That crucial point in our relatedness to nature brings into the center of the picture the basic theme of this book, man’s need for awareness of himself. One must be able to affirm his person despite the impersonality of nature, and to fill the silences of nature with his own inner aliveness.

Caspar David Friedrich, Moonrise by the Sea, ca. 1821

It takes a strong self—that is, a strong sense of personal identity—to relate fully to nature without being swallowed up. For really to feel the silence and the inorganic character of nature carries a considerable threat. If one stands on a rocky promontory, for example, and looks at the sea in its tremendous rising and falling of swells, and if one is fully and realistically aware that the sea never “has a tear for others’ woes nor cares what any other thinks,” that one’s life could be swallowed up with scarcely an infinitesimal difference being made to the tremendous, ongoing, chemical movement of creation, one is threatened. Or if one gives himself to the feeling of the distance of the far mountain peaks, permits himself to “empathize” with their heights and depths, and if one is aware at the same moment that the mountain “never was the friend of one, nor promised what it could not give,” and that one could be dashed to pieces on the stone floor at the foot of the peak without his extinction as a person making the slightest difference to the walls of granite, one is afraid. This is the profound threat of “nothingness,” or “nonbeing,” which one experiences

when he fully confronts his relation with inorganic being. And to remind one’s self, “Dust thou art, to dust returnest” is hollow comfort indeed.

Such experiences in relating to nature have too much anxiety for most people. They flee from the threat by shutting off their imagination, by turning their thoughts to the practical and humdrum details of what to have for lunch. Or they protect themselves from the full terror of the threat of nonbeing by making the sea a “person” who wouldn’t hurt them, or by taking refuge in some belief in individual Providence and telling themselves, “He shall give his angels charge concerning thee . . . lest at any time thou dash thy foot against a stone.” But to flee from one’s anxiety, or to rationalize one’s way out of it, only makes one weaker in the long run.

It requires, we have said, a strong sense of self and a good deal of courage to relate to nature creatively. But to affirm one’s own identity over against the inorganic being of nature in turn produces greater strength of self. (…) We wish here only to emphasize that the loss of the relation to nature goes hand in hand with the loss of the sense of one’s own self. “Little we see in Nature that is ours,” as a description of many modern people, is a mark of the weakened and impoverished person.

Tags: Alienation, anxiety, art, Caspar David Friedrich, German painter, man and nature, Man's Search for Himself, mountains, Nature, psychology, Rollo May, Romanticism, Sea, sublime

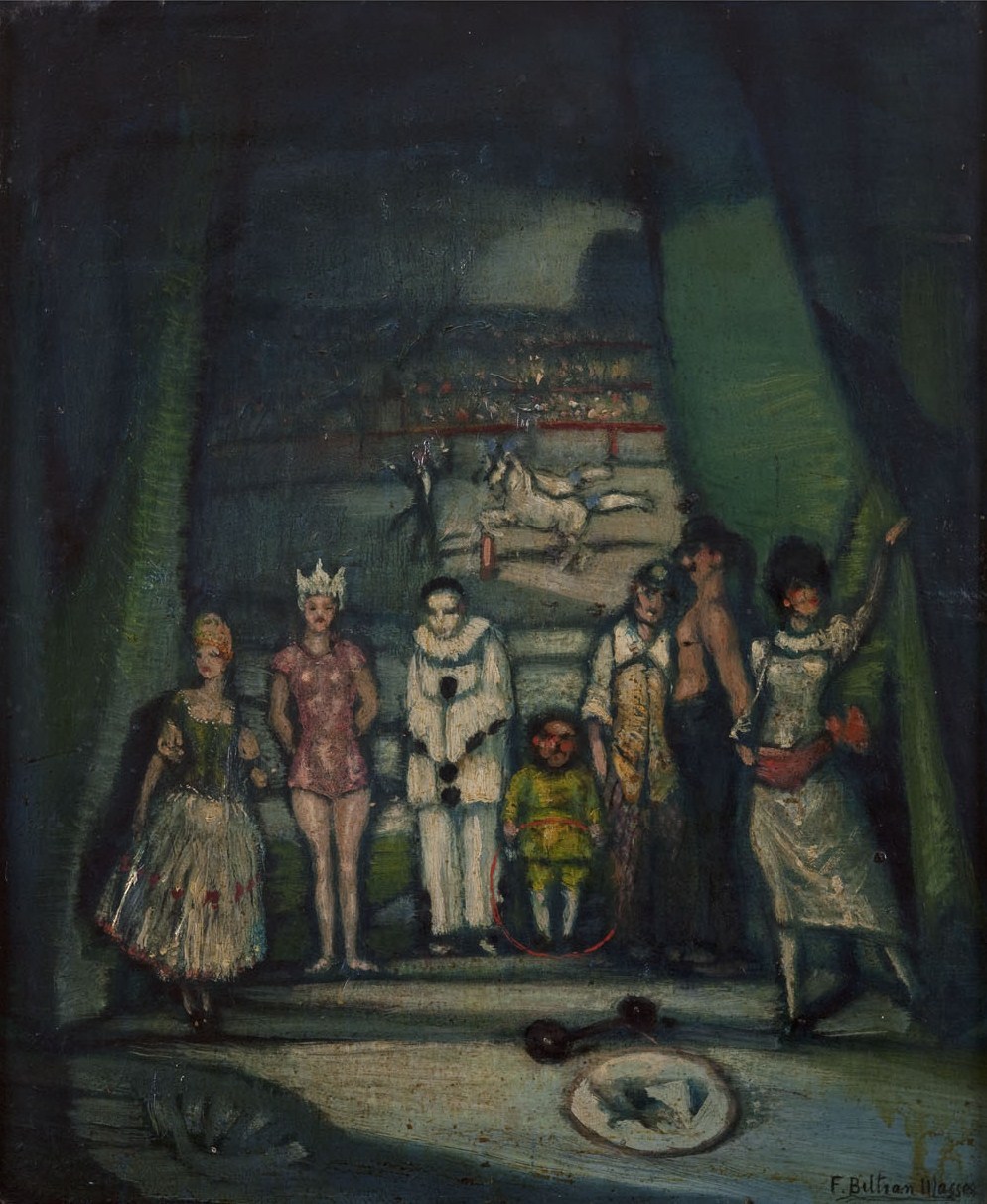

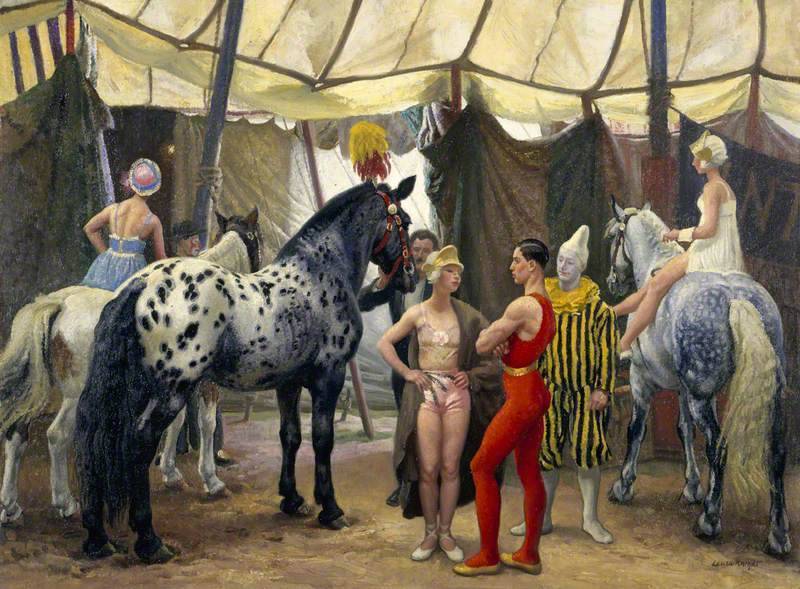

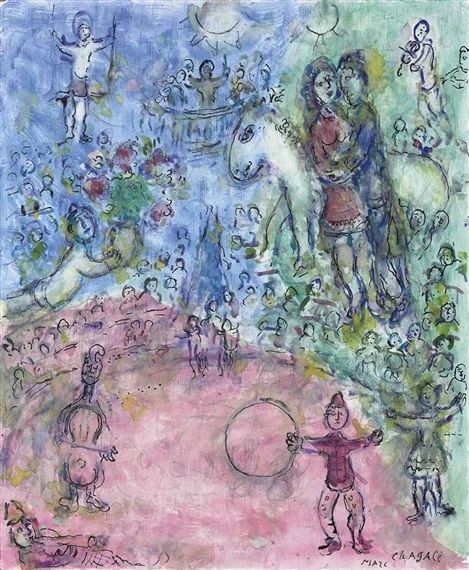

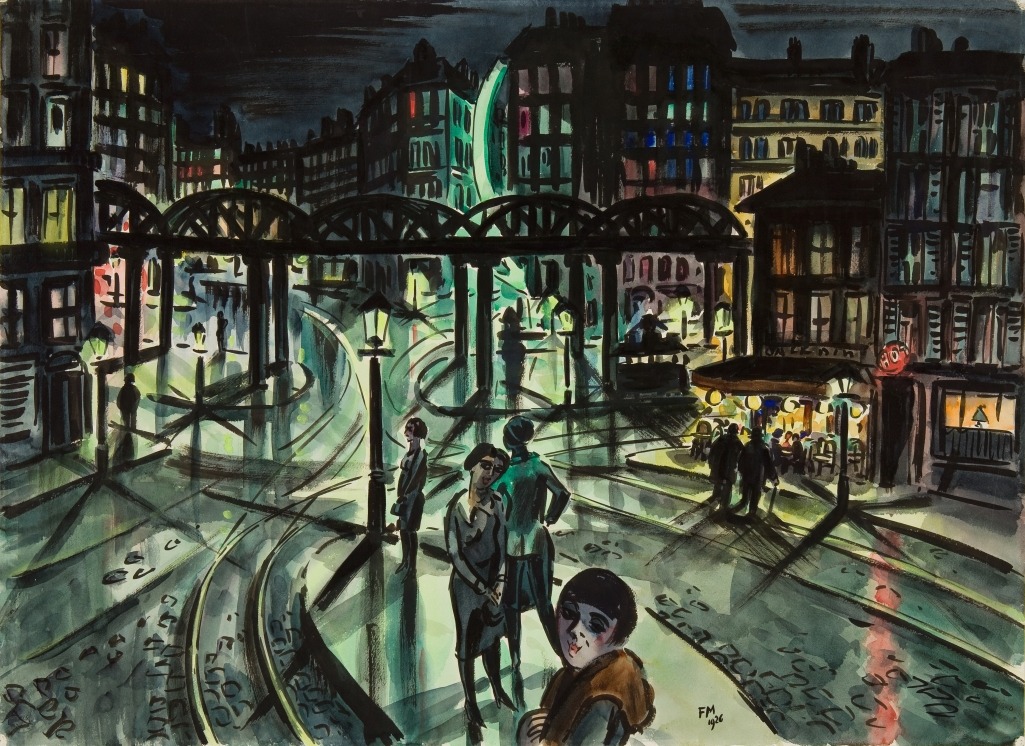

Laura Knight, The Fair, 1919

Laura Knight, The Fair, 1919