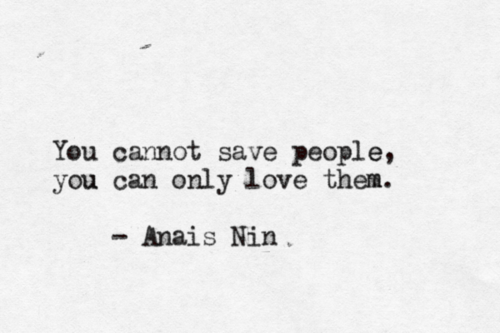

These days I have been reading Anaïs Nin’s essays, and thinking about them a lot, in particular I am fascinated by her devoted diary keeping, the conflict of dreams vs reality, the reason one writes and the importance of spontaneity and naturalness in writing.

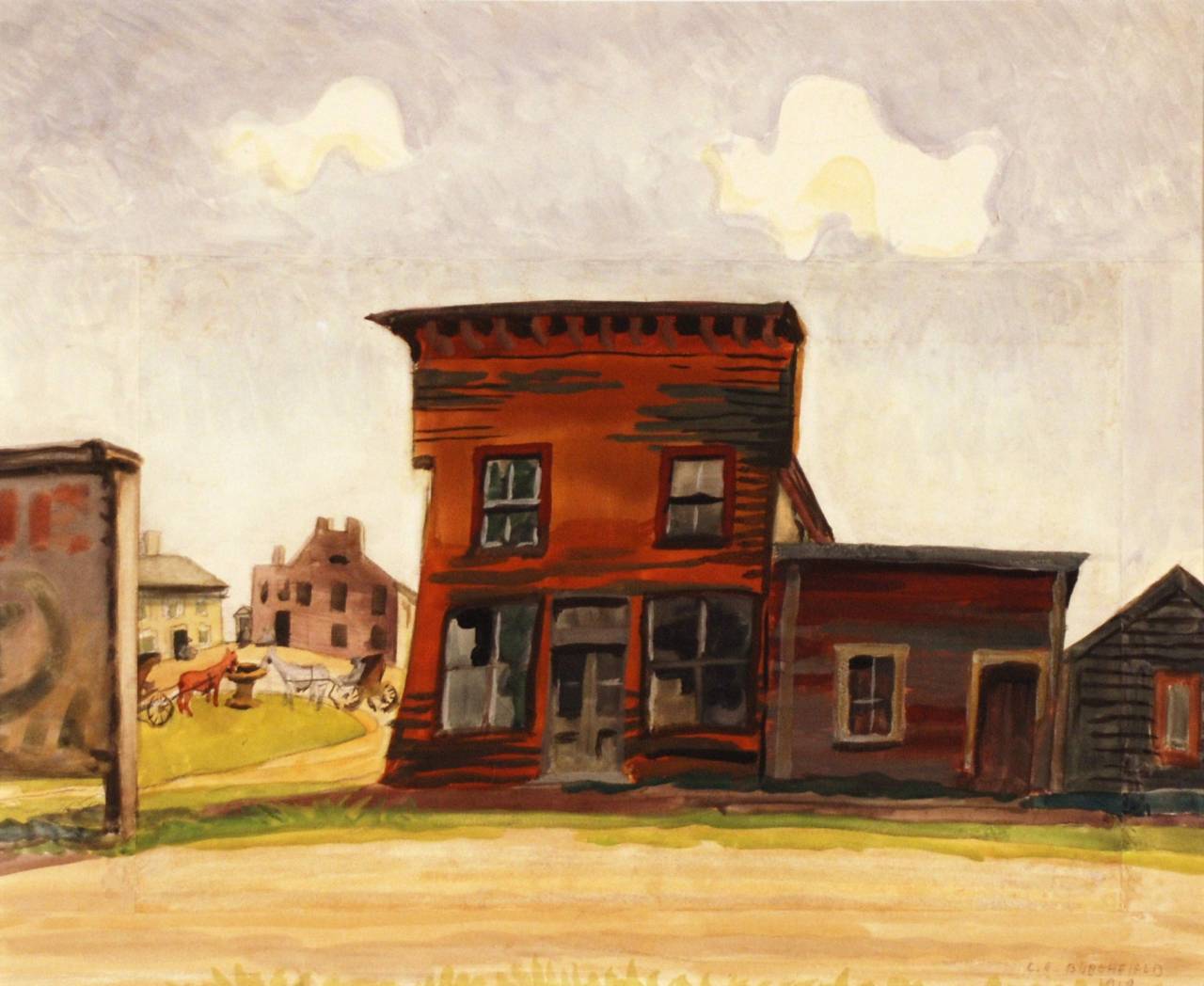

Anais Nin in Havana, c. 1920s

Anais Nin in Havana, c. 1920s

“I can connect deeply or not at all.”

A sensitive and imaginative child, Anais Nin started writing her diary in 1914 at the age of eleven. Other girls her age would probably pretend they were writing to their imaginary friends, but Anais envisaged her diary as a string of letters to her father who had abandoned the family and left to live with his lover. How poignant to imagine this gentle and pale, dark-haired and sad-eyed little girl clutching her notebook, living half in those words and half in dreams, and know that her desire for writing appeared out of her childlike sadness, longing and a desire to gain his love. What began as a desire to be loved and to connect, not only with her father, but with the world, turned into a lifelong occupation; Anais continuously wrote her diary since the age of eleven to her death in 1977.

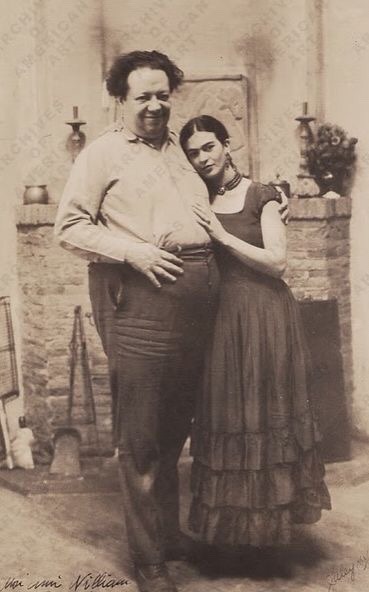

Nin’s writing fascinates me as much as her family ancestry and her life. She was born in France to Cuban parents; her mother Rosa was a singer of French and Danish descent, and her father Joaquín was a pianist born in Havana, but the hot Catalan Spanish blood flew his veins. Anais spent her childhood in Spain, teenage years in America where she posed for painters, got married in 1923 in Havana to Hugo Parker Guiler, moved to Paris the following year, then lived in the United States for the rest of her life. While in Paris, she wrote the most interesting part of her diary and had an affair with the writer Henry Miller which is documented in “Journal of Love: Henry and June”, and also studied flamenco dancing! It was in Paris that she started pondering seriously on the matter of being an artist, a writer, and she realised there, in the grey suburbs of shiny Paris, that just being a wife isn’t fulfilling. Her Journals of Love witness her sensual and artistic awakening, and her, at the same time, passionate and intellectual relationship with Henry. She says: “How wrong it is for a woman to expect the man to build the world she wants, rather than to create it herself.”

Creating a world of one’s own, through writing and daydreaming

“Don’t wait for it,” I said. “Create a world, your world. Alone. Stand alone. And then love will come to you, then it comes to you. It was only when I wrote my first book that the world I wanted to live in opened to me.” (The Diary of Anais Nin, Vol 1: 1931-34)

And created a world she did! She stopped expecting the world to come to her, and instead gave herself to her diary, and by building a rich inner life, the real life began.

“Why one writes is a question I can answer easily, having so often asked it of myself. I believe one writes because one has to create a world in which one can live. I could not live in any of the worlds offered to me — the world of my parents, the world of war, the world of politics. I had to create a world of my own, like a climate, a country, an atmosphere in which I could breathe, reign, and recreate myself when destroyed by living. That, I believe, is the reason for every work of art. (…)

We write to heighten our own awareness of life. We write to lure and enchant and console others. We write to serenade our lovers. We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospection. We write, like Proust, to render all of it eternal, and to persuade ourselves that it is eternal. We write to be able to transcend our life, to reach beyond it. We write to teach ourselves to speak with others, to record the journey into the labyrinth. We write to expand our world when we feel strangled, or constricted, or lonely… If you do not breathe through writing, if you do not cry out in writing, or sing in writing, then don’t write because our culture has no use for it. When I don’t write, I feel my world shrinking. I feel I am in prison. I feel I lose my fire and my color. It should be a necessity, as the sea needs to heave, and I call it breathing.“

I know this quote by heart because it really chimes with me, but there is one line in particular which I can’t get out of my mind for two weeks now: “We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospection.” To write, then, means to trick transience because a moment of beauty is captured forever in words, and what a luxury a memory is because we can play it out in our minds as many times as we want. A sunset and a sight of a flower, can give birth to stories and daydreams in our imagination, the past can be relived and transformed, beautified and idealised until it becomes a whole new fantasy. Writing brings freedom and it shields you from reality, it’s like a soft flimsy dusty pink veil of protection, it offers beauty instead of loneliness. Writing heals the wounds inflicted by living, and turns our tears into flowers.

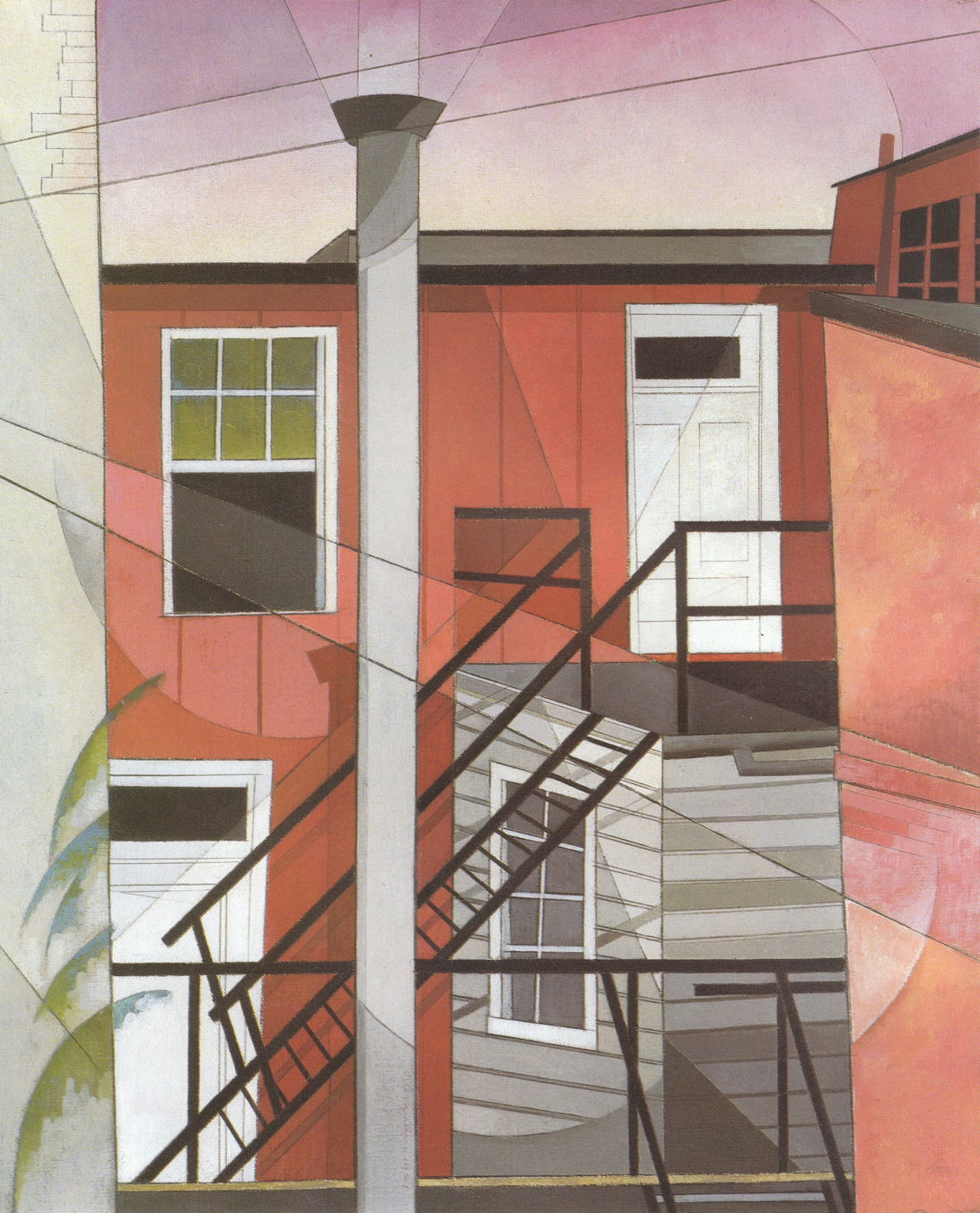

Henry Miller and Anais Nin, c. early 1930s

The Importance of Diary

Anais’s literary legacy lies in her diaries, and in her essay “On Writing”. self-published in 1947, she praises her diary for its spontaneity and naturalness:

“It was while writing a Diary that I discovered how to capture the living moments. Keeping a Diary all my life helped me to discover some basic elements essential to the vitality of writing.

When I speak of the relationship between my diary and writing I do not intend to generalize as to the value of keeping a diary, or to advise anyone to do so, but merely to extract from this habit certain discoveries which can be easily transposed to other kinds of writing.

Of these the most important is naturalness and spontaneity. These elements sprung, I observed, from my freedom of selection: in the Diary I only wrote of what interested me genuinely, what I felt most strongly at the moment, and I found this fervor, this enthusiasm produced a vividness which often withered in the formal work. Improvisation, free association, obedience to mood, impulse, bought forth countless images, portraits, descriptions, impressionistic sketches, symphonic experiments, from which I could dip at any time for material.“

In the same essay she points to the importance of writing continuously, and the dangerous of perfectionism:

“To achieve perfection in writing while retaining naturalness it was important to write a great deal, to write fluently, as the pianist practices the piano, rather than to correct constantly one page until it withers. To write continuously, to try over and over again to capture a certain mood, a certain experience. Intensive correcting may lead to monotony, to working on dead matter, whereas continuing to write and to write until perfection is achieved through repetition is a way to elude this monotony, to avoid performing an autopsy. Sheer playing of scales, practice, repetition — then by the time one is ready to write a story or a novel a great deal of natural distillation and softing has been accomplished.”

“I am sick of my own romanticism!”

Another thing I love about Anais Nin is her ability to crystallise her thoughts and feelings so well, and in so few words. She gets to the point. Some writers would need thousands of words to explain why one writes, and they still wouldn’t deliver a wise or interesting definition. Anais lived equally in her words as she did in real life, and, as years went on, she mingled the two; her life and loves became a dream, and her inner life was enriched by real experiences. Her wisdom and intuitiveness, and her understanding of her own moods and emotions comes well in her writing and it gives it beauty.

I have learned, and am learning so much from Anais. Firstly, the already mentioned idea of creating a world of your own. Imagination, dreams and daydreams are just as real as real life, and to cultivate them is to cultivate your inner life. In the world dominated by extroverts, daydreaming is sadly seen as escapism, and not as a gift of transcending reality. Secondly, the importance of emotional experiences, she says “And nothing that we do not discover emotionally will have the power to alter our vision.” I learned a great deal through observing Anais’s reactions to some sad situations in her journals, mostly with love. Detaching yourself from life in moments of despair, and observing the situation rather than being in it, frees your from pain of living it and feeling you are one with it. Out of this detachment arises bliss, and even the situation which would usually cause me pain or sadness can seem trivial and laughable. At the same time, Anais allows herself to experience emotions, but grows from the experience and doesn’t let herself be drowned in the dark oceans of sadness.

Anais inspired me to never leave the blooming fragrant garden of my imagination and seek happiness in the dry barren desert of reality where pains loom on the horizon like tall green cactuses and eagles seek their prey. Sadness is a deceptive shadowy creature, and happiness is like warm golden rays of sun, it touches your for a moment but you cannot possess it fully. Passion, enthusiasm, rapture, Imagination, daydreams, eternal quest for beauty and abundance of love to give; these are some things that are mine entirely, cannot be taken away but grow with me. In a way, writing connects our inner world with the real world. To end, here is another brilliant quote by Anais:

“I am an excitable person who only understands life lyrically, musically, in whom feelings are much stronger as reason. I am so thirsty for the marvelous that only the marvelous has power over me. Anything I can not transform into something marvelous, I let go. Reality doesn’t impress me. I only believe in intoxication, in ecstasy, and when ordinary life shackles me, I escape, one way or another. No more walls.”

Tags: 1930s, 20th century writer, Anais Nin, artistic awakening, creating, Cuban writer, daydreaming, diary, dream, dreams, emotions, Henry and June, Journal of Love, Paris, reality, sensual, we write to taste life twice, writer, writing

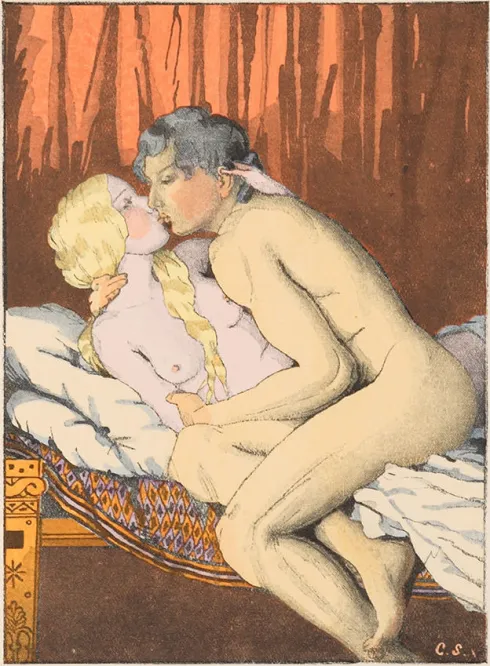

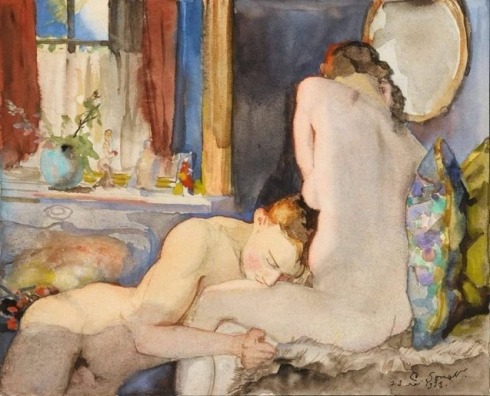

Konstantin Somov, The Lovers, 1933

Konstantin Somov, The Lovers, 1933