“Pleasure is addictive. It can have all the elements and attributes of a fever. Pleasure is a dream.”

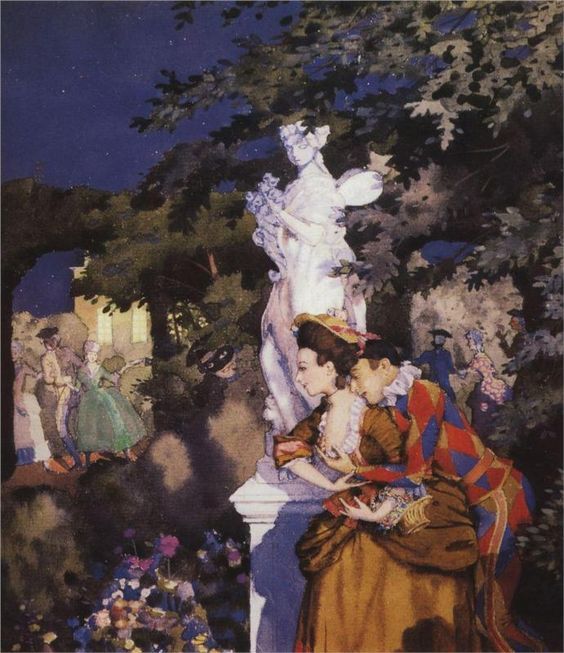

Konstantin Somov, Italian Comedy, 1914

Konstantin Somov, Italian Comedy, 1914

I had written about Konstantin Somov carnival scenes, in particular his watercolour “Lady and Pierrot” from 1910, but today let us take a look at some of his other carnival scenes filled with figures of Harlequins, Pierrots and elegant Rococo ladies. In his choice of themes Somov was greatly influenced by the eighteenth century painters and themes, in particular the elegant, fanciful world of Watteau’s art where everyone is searching love and happiness in the ambience of elegant parks with marble statues and forest groves with whispering ivy-overgrown trees. If you take a look at Somov’s paintings that I’ve chosen to present here, “The Italian Comedy”, “The Fireworks”, and even the scenes from the notorious “Book of the Marquise”, and then compare them with the paintings by Watteau, it is easy to see the similarities. Still, it is not to say that Somov’s paintings are mere copies of Watteau, not at all, for his artworks have a distinct flair and are rich in colours and a tad more flirtatious and daring than Watteau’s which I enjoy greatly. In Somov’s carnival scenes we find none of that suble yet tangible wistfulness, no sense of transience and fragility that permeates Watteau’s paintings. In Somov’s portrayal of the carnival and leisure, there is a mood of frivolity, of carelesness, of unashamed pleasure; let the champagne flow and kisses, wherever they may, fall!

I feel that Somov’s art, not just the paintings here but many of his other artworks as well, are a visual companion to the line “Pleasure is addictive, pleasure is a dream”. I mean, the figures in Somov’s art just cannot seem to get enough of it – the pleasure, in whichever form; the parties, the laughing, the dancing, the kissing, the drinking, the gambling, the staying up all night and gazing at fireworks, it’s just constant frivolity and playful decadence. In Somov’s painting “Italian Comedy”, painted in 1914, we have a playful garden scene. The smiling Pierrot takes the centre stage, but there is also a Harlequin and a lady dressed in a striped Rococo gown and a Lady Harlequin as well. Despite the setting being a garden, it feels oddly like a stage, choreographed and somewhat stiff, more so than Somov’s other carnival scenes. In the background there are fireworks; another motif seen often in these paintings by Somov.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Harlequin and Columbine, 1716-1718

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Harlequin and Columbine, 1716-1718

Jean-Antoine Watteau, The Italian Comedy, 1716

In Watteau’s painting “Columbine and Harlequin”, painted two hundred years before Somov’s painting, there is a similar garden-carnival scenes. The centre is occupied by a dashing, flirty Harlequin in his vibrant attire and he is trying to seduce Columbine. Look at his hand gesture, I wonder what joke is he telling her? She doesn’t seem all that amused, perhaps it is Pierrot who is on her mind… In the background there are other young people, yearning for love and fun. I do love Watteau’s paintings and now Somov’s watercolours and other paintings are giving me the same thrill. The art of the early twentieth century with its radicalism and experiementation, the harsh squares and rectangles of Cubism, the garish colours of Fauvism, the angst and horror of Expressionism, none of it was for Somov who looked back in time when seeking inspiration, who wanted to drink from the fountain of beauty and love, and not from fountain of modernity and speed.

Konstantin Somov strikes me as a man who painted what he could not live, and that is partly true as reveiled in his letter to a fellow painter Elizaveta Zvantseva, dated 14th of February 1899: “Unfortunately, I still have no romance with anyone—flirting, perhaps, but very light. But I’m tired of being without romance—it’s time, otherwise life passes by, and youth, and it becomes scary. I terribly regret that my character is heavy, tedious, gloomy. I would like to be cheerful, easy-going, amorous, a daredevil. Only such people have fun, those not afraid to live!” Also, the world that we see in both Watteau and Somov’s art is a world that… simply does not exist, and never will come a day when it will exist, only perhaps in the hearts and minds of the imaginative romantics and in these beautiful canvases that we can gaze at for hours and fantasise. For me, these paintings are a world just beyond reach and so gazing at them fills me with excitement, but also provokes inside me an inexplicable yearning that may, if I allow it, turn into a heartache.

Konstantin Somov, Fireworks, 1929

Now, again, I would love to connect these Wattea and Somov’s carnival scenes with a passage from Peter Ackroyd’s book “Venice: Pure City” because I find it fascinating:

“The Carnival was instituted at the end of the eleventh century, and has continued without interruption for almost seven hundred years. After a period of desuetude it was resurrected in the 1970s. “All the world repairs to Venice,” John Evelyn wrote in the seventeenth century, “to see the folly and madness of the Carnevall.” It was originally supposed to last for forty days, but in the eighteenth century it was sometimes conducted over six months. It began on the first Sunday of October and continued until the end of March or the beginning of Lent. This was also the theatre season. In a city that prided itself on transcending nature, it was one way of defying winter. Yet if the festivities last for half a year, does “real” life then become carnival life? It was said in fact that Venice was animated by a carnivalesque spirit for the entire year. It was no longer a serious city such as London, or a wise city such as Prague.

There were bands and orchestras in Saint Mark’s Square; there were puppet shows and masked balls and street performers. There were costume parties in the opera houses, where prizes were awarded for the best dress. There were elaborate fêtes with gilded barges, liveries of gold and crimson, gondolas heaped with flowers. The Venetians, according to William Beckford in the 1780s, were “so eager in the pursuit of amusement as hardly to allow themselves any sleep.” In this season, everyone was at liberty. Evelyn described the Carnival as the resort of “universal madnesse”.

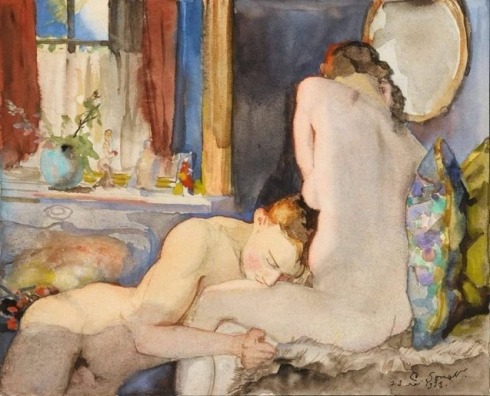

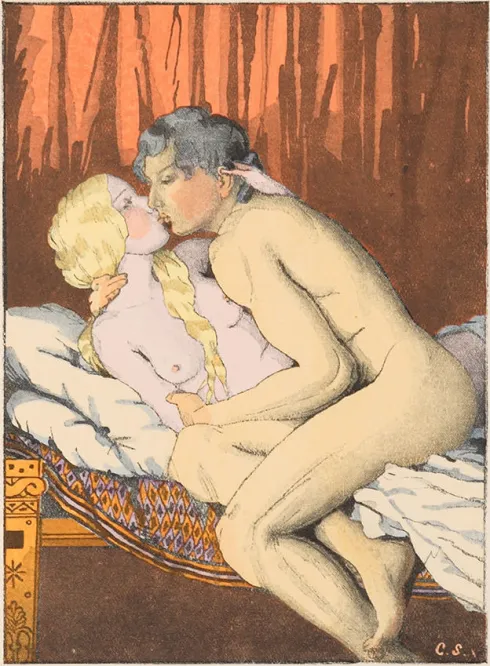

Konstantin Somov, Book of the Marquise. Illustration 8, 1918, lithography

Konstantin Somov, Book of the Marquise, 1918, lithography

(…)There were firework displays; the Venetians were well known for their skill at pyrotechnics, with the reflection of the coloured sparks and flames glittering upon the water. There were rope-walkers and fortune-tellers and improvisatori singing to the guitar or mandolin. There were quacks and acrobats. There were wild beast shows; in 1751 the rhinoceros was first brought to Venice. There were the elements of the macabre; there were mock funeral processions and, on the last day of the Carnival, a figure disfigured by syphilitic sores was pushed around in a barrow. Here once more is the old association between festivity and the awareness of death.

Venetians dressed up as their favourite characters from the commedia dell’arte. There was Mattacino, dressed all in white except for red shoes and red laces; he wore a feathered hat, and threw eggs of scented water into the crowd. There was Pantalone, the emblem of Venice, dressed in red waistcoat and black cloak. And there was Arlecchino in his multi-coloured costume. There were masked parties and masked balls.

(…) Pleasure is addictive. It can have all the elements and attributes of a fever. Pleasure is a dream.”

Tags: 1910s, 1914, art, art blog, carnival, celebration, Columbine, fantasy, festival, fun, Harlequin, Italian Comedy, Italy, Konstantin Somov, love, Pierrot, Pleasure, pleasure is a dream, Russian art, Russian painter, Venice

Konstantin Somov, The Lovers, 1933

Konstantin Somov, The Lovers, 1933

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Harlequin and Columbine, 1716-1718

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Harlequin and Columbine, 1716-1718