“Something in the way she moves

Attracts me like no other lover

Something in the way she woos me”

Marc Chagall, Les Amoureux, 1928

Marc Chagall, Les Amoureux, 1928

These days I am not merely thinking about Marc Chagall’s artworks – I am living in them, and oh my, what a wonderful place to live in. In particular, I am enjoying gazing at his painting “The Lovers” from 1928. The painting, as suggested in the title, shows two lovers lost in an embrace, floating somehere in the sky, somewhere in the world of their own. The motif of lovers is something that pervades Chagall’s canvases. While the woman is gazing in the distance, the man’s head is leaned on her shoulder, as if seeking comfort. She is looking into the future and he is holding onto her. The crimson colour of the woman’s dress is echoed by the fuchsia coloured background and in the colour of the roses on the right side of the painting. A blue sky with a large full moon and a bird flying by is seen emerging from the bottom right side of the canvas.

Chagall’s lovers don’t live in the real, material, tangible world around us, no, they live in the realm of love, in the soft, feathery, fragrant and sweet clouds of love. Dancing in the sky in the rhythm of each other’s hearts, floating through the night sky like shooting stars. Even when the space around the lovers is real, with its little cottages, wooden fences, cows, goats, fiddlers and mud, this ugly banality is transformed and transcended, it is as if the lovers are completely untouched by it all. It’s like threading over the fresh snow and leaving no footprints. In Chagall’s art the “down to earth” and “dreamy” meet and collide in a perfect way. Chagall is the most tender-hearted man in the world of art and his innocent, imaginative and childlike vision of the world is obvious in his canvases. The figure that always haunts his art is the slender figure of a black haired woman; his beloved wife Bella Rosenfeld.

Marc Chagall, The Promenade, 1917-18

Marc Chagall, The Promenade, 1917-18

Their early days of love are captured in a series of paintings such as “Birthday”, “Promenade” and “Over the Town”. There is a playful innocence and a pure display of affections in these paintings that chimes with me so well. Chagall takes the phrase “floating in the air” quite literally because in these paintings the lovers are flying indeed; the power of their love is so strong that not even gravity can stop it.”The Promenade” shows Chagall and Bella having a picnic on a meadow outside town but then suddenly Bella is flying in the air like a pink ballon. Chagall is holding her hand but he too will quickly rise into the clouds following his darling. Painting “Over the Town” shows an embracing couple flying above the little houses of the little town which is now too small to contain the vastness of the love that they feel. The houses and the landscape under them both seem faded, as if seen in a dream or in a memory, painted in shades of grey. Only that one house is red, like a crimson red heart pulsating in the rhythm of love.

“Over the Town” is a painting which thematically and aesthetically goes hand in hand with Chagall’s painting “Birthday” painted in 1915; both paintings show lovers magically lifted from the ground by the power of love, the power against which all the mundane things in life suddently seem gray and irrelevant. When I gaze at this paintings, these lovers which all have faces like Chagall and Bella, the lyrics of the Beatles’ song “Something” come to mind;

“Something in the way she moves

Attracts me like no other lover

Something in the way she woos me

I don’t want to leave her now

You know I believe and how

Somewhere in her smile she knows

That I don’t need no other lover

Something in her style that shows me

I don’t want to leave her now

You know I believe and how

You’re asking me will my love grow

I don’t know, I don’t know

You stick around, now it may show

I don’t know, I don’t know…“

Marc Chagall, Birthday, 1915

I can imagine Chagall gazing at Bella and musing to himself “something in the way she moves attracts me like no other lover, something in the way she woos me…” In the painting “Birthday” it is Chagall who is flying above Bella though she too is about to join him soon. Again we see the everyday transformed into the wonderful; a simple room, Bella in her everyday clothes, yet there is magic, the magic of love which transforms everything. Bella wrote about this feeling which Chagall so beautifully portrays in his paintings: “I suddenly felt as if we were taking off. You too were poised on one leg, as if the little room could no longer contain you. You soar up to the ceiling. Your head turned down to me, and turned mine up to you… We flew over fields of flowers, shuttered houses, roofs, yards, churches.” In most paintings Bella is portrayed as wearing the same clothes she would have been wearing everyday and on the photos which exists of her, and the town we see is their hometown of Vitebsk in Belorus. Both of these elements bring a domestic kind of familiarity which becomes magical and sweet when Chagall portrays it.

Marc Chagall, Over the Town, 1913

The love at first sight between Bella and Chagall started in 1909 when a beautiful daughter of a rich jeweller met the poor and aspiring painter who worked as an apprentice for Leon Bakst and it lasted for thirty five years until Bella, sadly, passed away three months shy of her forty-nineth birthday in 1944. In his autobiography “My Life”, Chagall writes of Bella: “Her silence is mine, her eyes mine. It is as if she knows everything about my childhood, my present, my future, as if she can see right through me; as if she has always watched over me, somewhere next to me, though I saw her for the very first time. I knew this is she, my wife. Her pale colouring, her eyes. How big and round and black they are! They are my eyes, my soul.”

Bella, although seemingly a quiet, pale and withdrawn girl, was enthusiastic about Chagall as well, and later wrote about being mesmerised by his ethereal pale blue eyes: “When you did catch a glimpse of his eyes, they were as blue as if they’d fallen straight out of the sky. They were strange eyes … long, almond-shaped … and each seemed to sail along by itself, like a little boat.“ She also wrote of their first meeting: “I was surprised at his eyes, they were so blue as the sky … I’m lowering my eyes. Nobody is saying anything. We both feel our hearts beating.“

Marc Chagall and Bella in Paris, 1938

Marc Chagall and Bella, c 1920

Chagall’s paintings reflect his way of thinking, he said; “If I create from the heart, nearly everything works; if from the head, almost nothing.” These are painting created from the heart, indeed. There is no logic, rationality or coldness about his art. Even when he paints in the Cubist manner, his squares and rectangles are not harsh but somehow still coated in the colour of dreams. Chagall had no interest in Cubism and Impressionist and was of an opinion that art is the “state of the soul.”

Marc Chagall, Lovers in Pink, 1916

Marc Chagall, Grey Lovers, 1917

When I am in love I live not in real world but in Chagall’s paintings. I am flying in the night sky and I am bathed in that gorgeous blueness. I am smiling at the stars and they are smiling back at me. Their golden dust is falling all over my white tulle dress. I am floating above the bridges, forests, meadows, flower fields, little houses with red roofs. I hear the violins, and flute, and the guitar, and I am carried away by that sweet music. I smell the violets, the roses, the lily of the valley; what sweet scents fill this warm summer night. Love is a warm summer night. My heart is overflowing with love and bursting into a thousand ruby red rose petals, and the petals fall and fall like a never-ending waterfall. I am melting into shapes, sounds and colours. I am the lilac, I am the crimson, I am the blue. I am the bird and the star. I am a rose petal carried by the wind, travelling far and far beyond. The coldness, dreariness and bleakness of winter Can.Not.Touch.Me. To live always in this way ahh that would be a life well lived. Is it possible? Is it really possible? Gazing at Chagall’s paintings makes me believe that it indeed is.

Tags: 1920s, art, art blog, Bella Rosenfeld, Bellorussian painter, Chagall, dreams, Dreamy, love, lovers, Marc Chagall, Paris, romance, sky, Something, Surrealism, The Beatles, Vitebsk

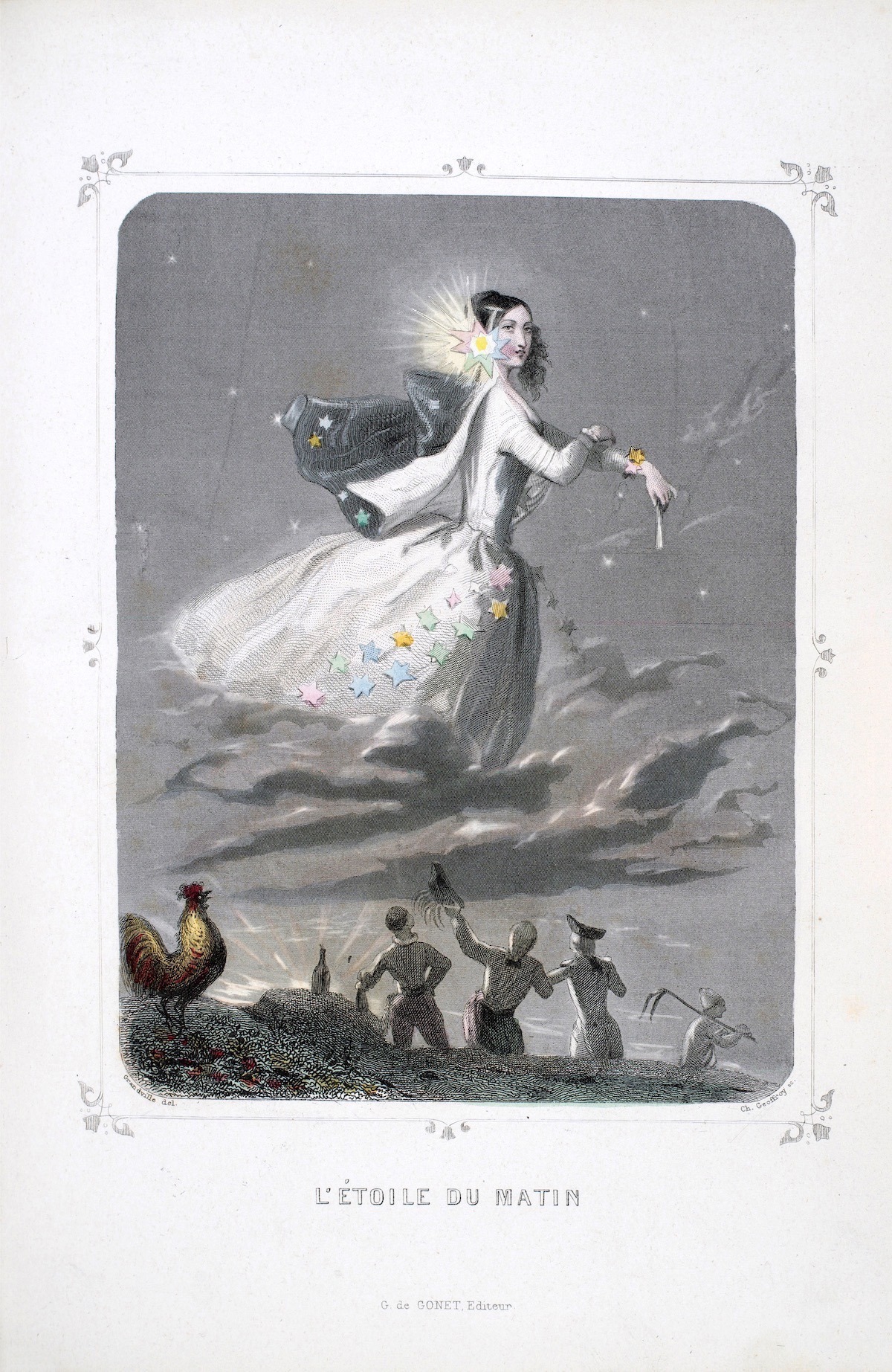

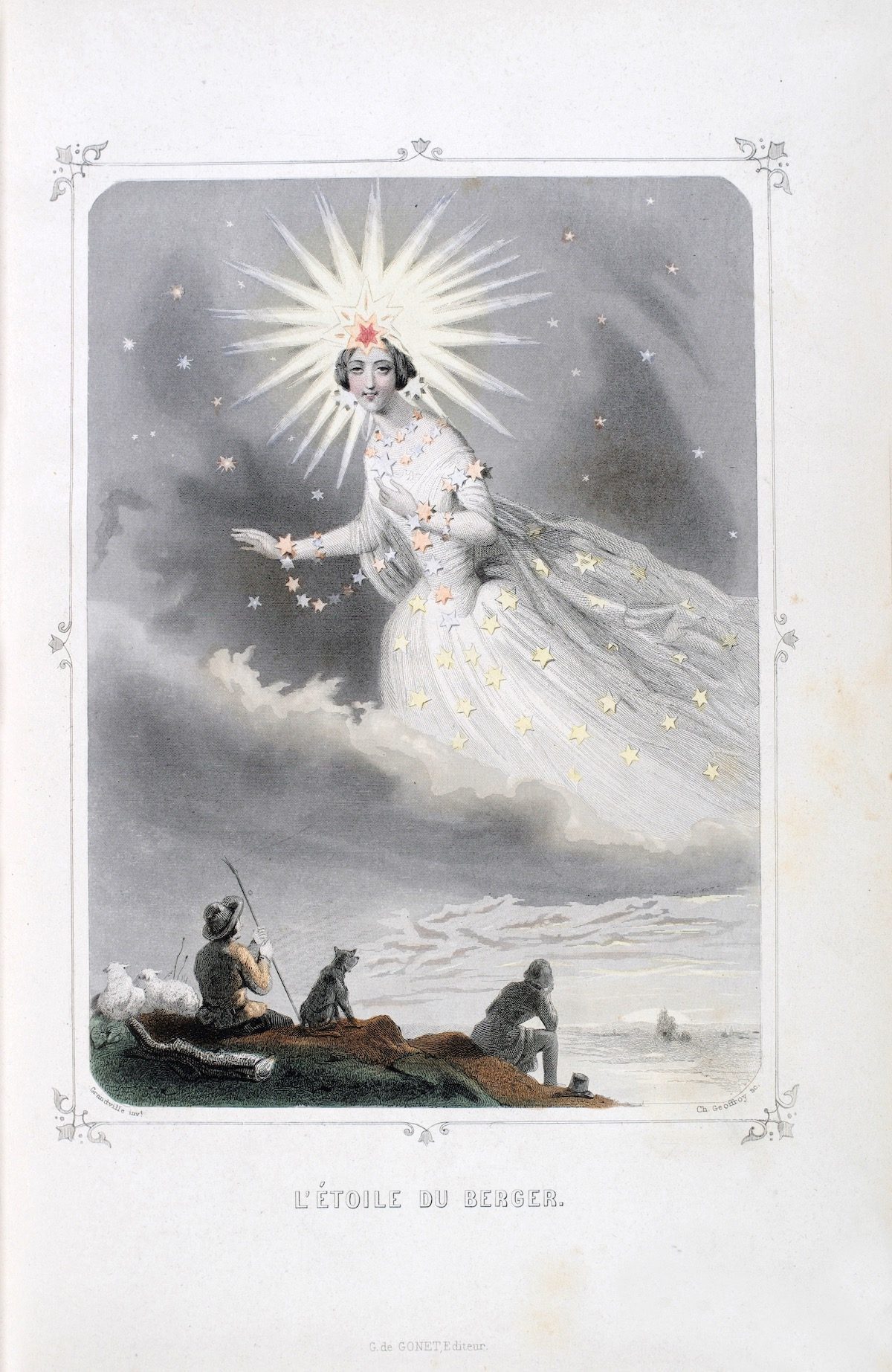

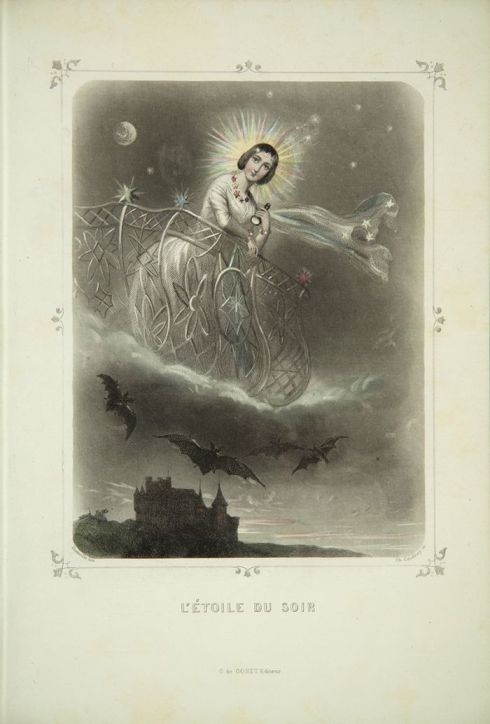

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849