“One day, though it might as well be somedayYou and I will rise up all the wayAll because of what you areThe prettiest star…”

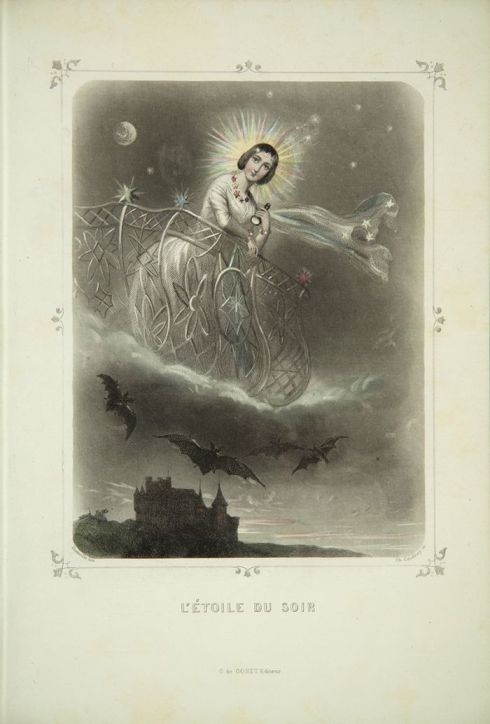

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849

French Romantic era artist and illustrator J.J. Grandville is one of the artists whose work has captivated me in the last year. The first artwork of his that I had encountered was his litograph “The Metamorphosis of Dreams” years ago, then last spring I had written about his series of illustrations “Flowers Personified” in which flowers are depicted as beautiful damsels with different personalities. These days it is his series called “Les Etoiles” or “The Stars” from 1849 that fascinates me the most. The night-time is, after all, is so much more romantic than day and the stars are so much more mysterious than the sun. In Grandville’s wonderful romantic-bordering-on-surrealism imagination the stars are again personified as beautiful women clad in the fashions of the day. My favourite at the moment is the one above, “The Evening Star” because of its Gothic mood. The illustration shows the evening star personified as a woman standing on the balcony that arises, not out of a castle tower, but out of a cloud and looking out into the night. Ah, but she should look into the mirror, for nothing is as lovely as the evening star itself! There are rays of gold stardust shining all about her head and we can see the moon in the distance behind her. In the lower part of the illustration, down on earth, there is gloomy and isolated Gothic looking castle and bats flying about it in an ominous manner. And yet the aura around the evening stair is so serene and bringht and pure that even the gloominess of the castle 0r the eeriness of the bats cannot ruin the magic of the scene.

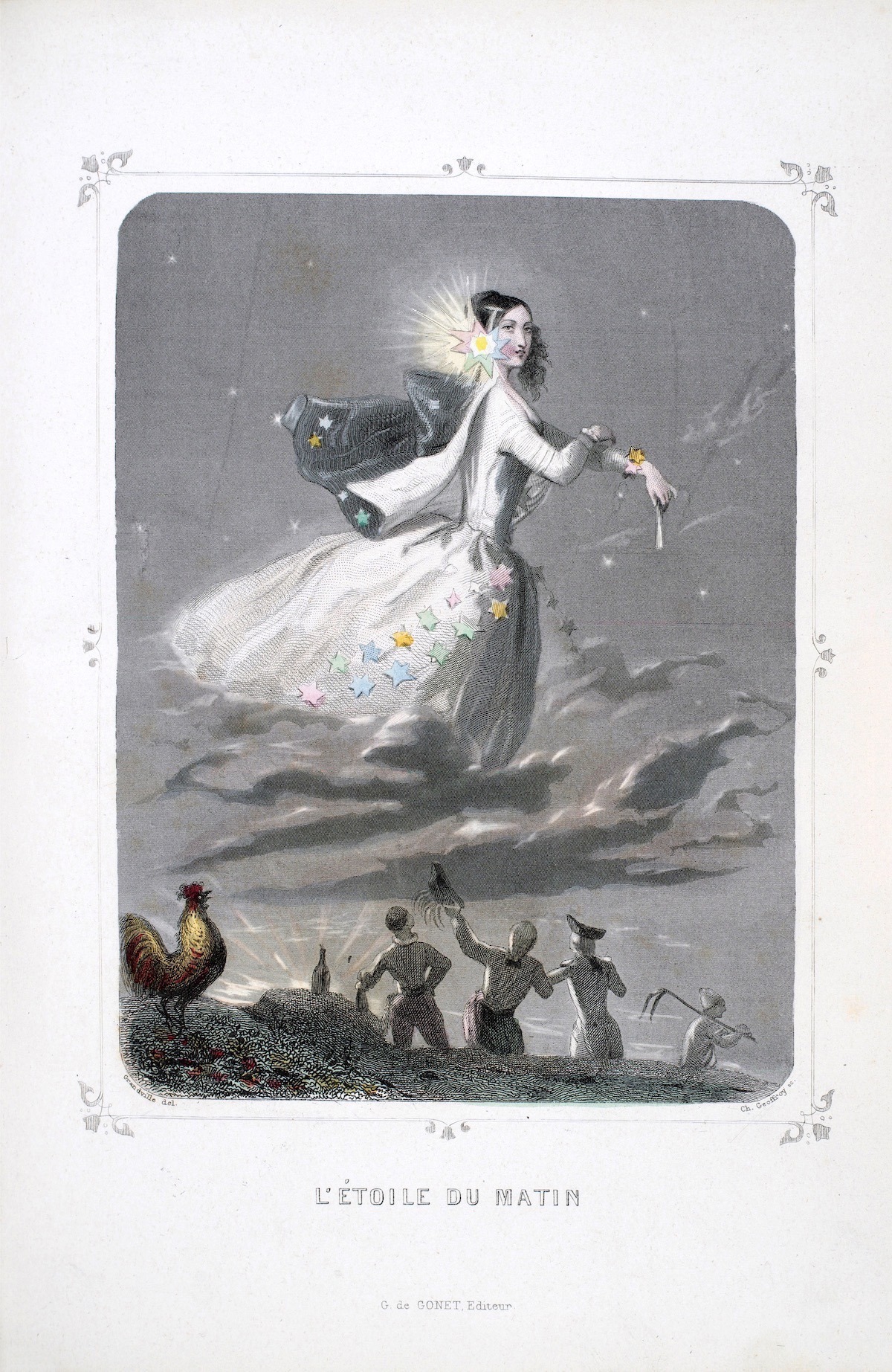

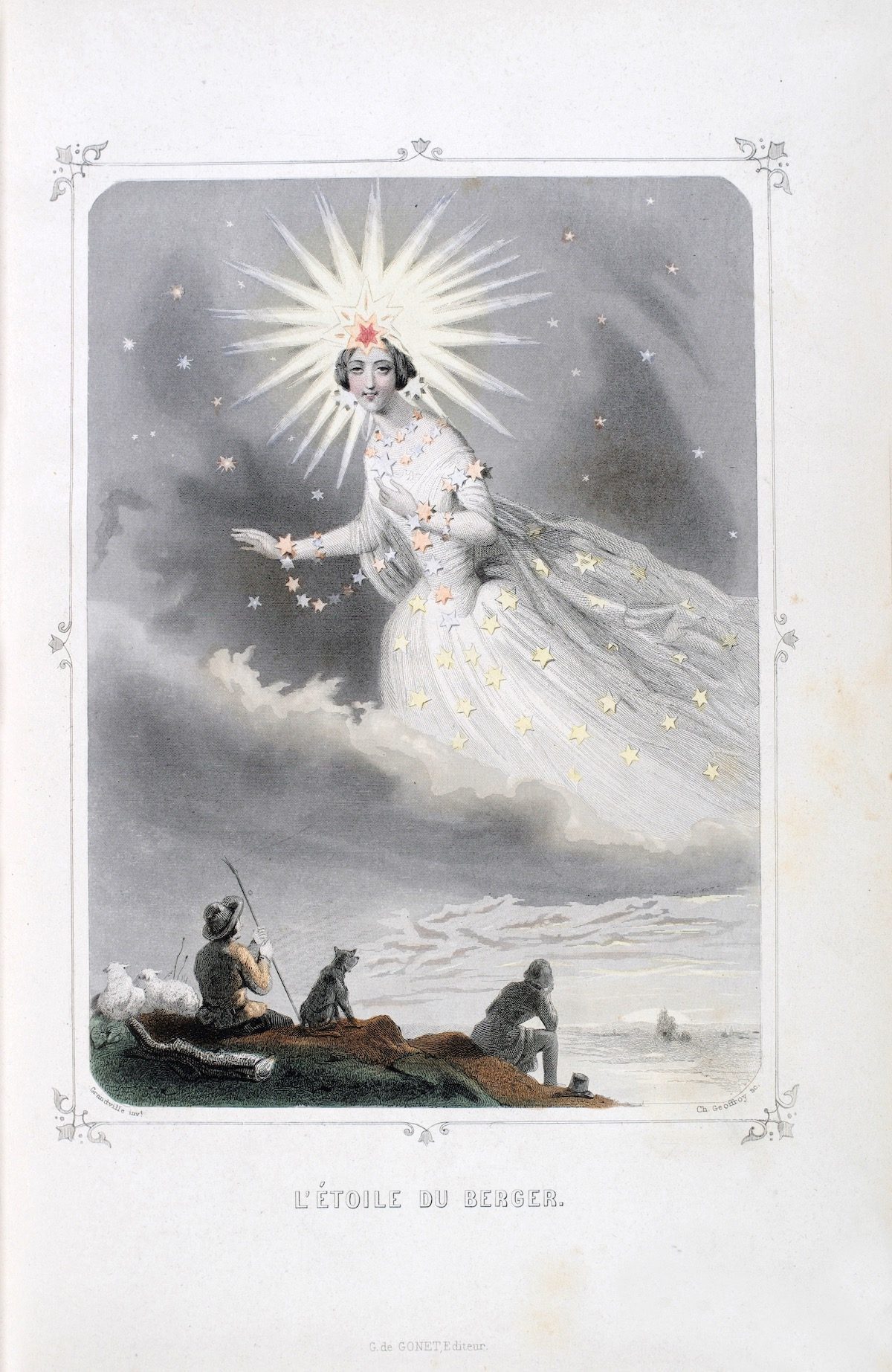

My other favourites are different in mood to the one above, but equal in beauty and intricacy. “The Morning Star” shows the morning star personified as a woman in a white gown in the 1840s style and a short black cape. Soft hair is dancing around her pale face and bright colourful stars are dancing above her dress and her cape in a groovy way. One star also serves as her hair decor. She is gliding through the night sky on a boat of clouds that are subservient to this goddess-like woman. She seems as soft as those clouds, as unattainable, as fleeting, for she is announcing a new day and a defeat of the night…at least for a while. Down from the ground she is being watched by some farmers, or workers, and a very curious and eager rooster who is depicted with more colour than the rest of the scene, to prove his importance of course, or at least he thinks so. “The Shooting Star” shows two lovers sitting on some meadow at night and up in the sky they are witnessing a shooting star, appearing for a moment intensely bright and strong on the night sky and then disappearing in an explosion of beauty. It is such a rare thing to see and no one can forget the moment they saw it, nor the person they were with when they saw it. I remember both times distinctly and I am very grateful that I got to see it. “The Shepherd’s Star” is a star personified as a very fashionable woman; her hair is adorned with many, many stars and the star that she is wearing as a headpiece is even grander. In contrast to the fashionable attire, her eyes seem drunk almost, or at least she seems in a sort of a haze; from love, or from drugs, or from joy, who knows. She is being watched by shepherds, a dog and some sheep. Just how magical and ethereal she is compared to the heavy, serious, and boring life down there on the ground. I love how soft the transitions are between the Lady Stars’ dresses and the clouds on which they are standing.

J.J. Grandville, The Morning Star, 1849

J.J. Grandville, The Shooting Star, 1849

J.J. Grandville, The Shepherd’s Star, 1849