January is always a time of sobering up, the hangover after a wild party of colours, vibrancy and magic that is December. I hate that! I want the party to go on perpetually, I don’t want to ‘sober’ up… ever. I want to always be drunk on music, art, poetry, love and beauty. And so this drab, lonely and grey month always passes in a whimsical mood for me because I celebrate Syd Barrett’s birthday every year. Syd Barrett was born on the 6th January 1946. But the celebration doesn’t begin and end on the 6th, oh no, it lingers on and on. I devote myself these days to listening to Pink Floyd’s early work, then Syd’s solo albums, reading one of my ultimate favourites: Julian Palacios’s wonderful book “Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd: Dark Globe”. The book instantly transports me back in time, to some whimsical, groovy, fairy tale-like place which perhaps never even existed, or it did, but only for a moment, like a shooting star. This is a post I originally wrote six years ago to celebrate Syd’s birthday, but I thought I’d repost it today because it’s been six years, come on, and I know there are many new readers now who probably have not read it. Enjoy!

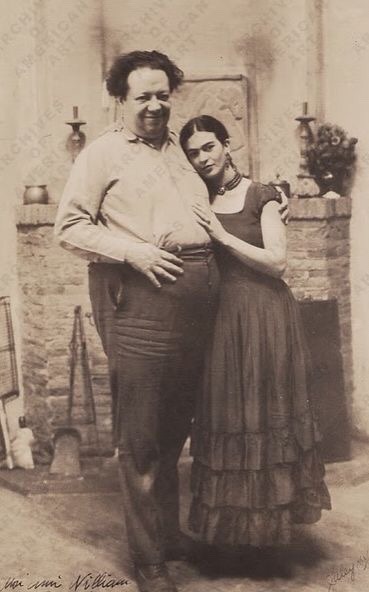

Syd Barrett with his painting, spring 1964

Syd Barrett with his painting, spring 1964

In this post we’ll discuss two of my favourite things in the world; Syd Barrett and art. Despite having achieved fame as a musician, first with Pink Floyd, and then later with two solo-albums, Syd was a painter first and foremost. He attended the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in London, and continued painting later in life. Let’s take a look at the artists and artworks Syd loved! Syd’s first passion was art. Some even went as far as saying that he was a better painter than a musician. Even David Gilmour said that Syd was talented at art before he did guitar. I’ve seen his paintings, and I wouldn’t agree. What could surpass the beauty that he’s created musically?

All quotes in this post are from the book ‘Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd: Dark Globe’ by Julian Palacios, and so is this one: ‘Waters brought older, upper-class friends round to Barrett’s house after school, among them Andrew Rawlinson and Bob Klose. They found him painting, paint below his easel, newspaper as a drop cloth and brushes on the windowsill. Painting and music ran in tandem, and Barrett was good at both. (…) Barrett sketched, painted and wrote, his output prolific.‘

Syd holding one of his paintings.

Syd holding one of his paintings.

Syd first attended the Saturday-morning classes at Homerton College, and then started a two-year programme at the Cambridgeshire College of Arts and Technology in autumn 1962. Along with his enthusiasm and skill at painting, he was good at memorising dates and authors of paintings. Here’s another quote that demonstrates Syd’s painting technique: ‘Syd drew and painted with ease, demonstrating a deft balance between shadow and light. He had a talent for portraits, though his subjects sometimes looked somewhat frozen. Best at quick drawings, Syd had a good feel for abstract art, creating bright canvases in red and blue.‘ It seems to me that Syd would have loved Rothko; an American Abstract-Expressionist artist who painted his canvases in strong colours with spiritual vibe.

Then, in autumn of 1964, Syd came to London to study at Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts. The curriculum at Camberwell was more rigorous than what Syd was used to at his previous college of arts: ‘At Camberwell, drawing formed the core curriculum. Tutors put Barrett through his paces working in different mediums and materials.‘ Syd’s art tutor, Christopher Chamberlain was taken with Syd’s tendency to paint in blunt, careless brushstrokes. Later in life, Barrett tended to burn his paintings, ‘psychedelic paintings, vaguely reminiscent of Jackson Pollock‘ because he believed that the point lies in creation and the finished product is unimportant. I can’t understand that at all – my paintings are my children.

Now I’ll be talking about seven artists that are in one way or another connected to Syd Barrett.

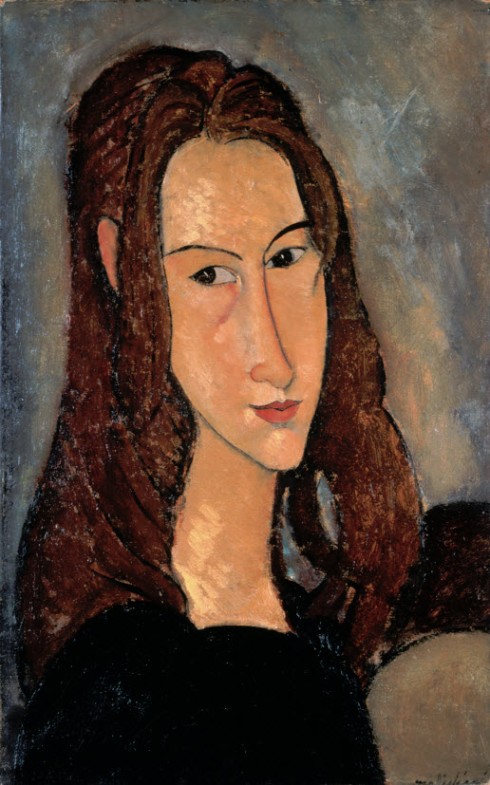

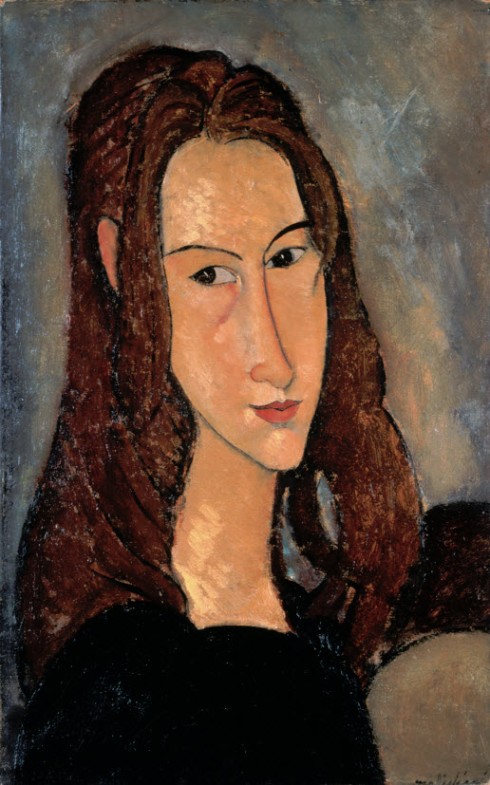

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne, 1918

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne, 1918

Modigliani

‘Sitting cross-legged in the cellar at Hills Road, Mick Rock was impressed as Syd rolled a joint with quick, nimble had. Nicely stoned, they listened to blues and talked about Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani, until the morning light peeked through the narrow slot windows.‘

Amedeo Modigliani; whose name itself sounds like a sad hymn of beauty, is perhaps one of the most unsung heroes of the art world. And the story of Amedeo and Jeanne’s love is perhaps the saddest of all. When Modigliani died, she couldn’t bear life without him so she threw herself out of the window, eight months pregnant at the time, oh how engulfed in sadness that January of 1920 must have been. Modigliani painted women, he painted them nude, and he painted their heads with large sad eyes, elongated faces, long necks and sloping shoulders. I think Modigliani expressed melancholy and the fragility of life like no other painter. I can’t tell for sure that Syd loved Modigliani, but since he talked about him, I take it that he was at least interested in the story behind his art. I would really like to hear that conversation between Syd and Rock.

Gustav Klimt, Beechwood forest, 1902

Gustav Klimt, Beechwood forest, 1902

Klimt

‘Appealing to Barrett’s Cantabrigian sensibilities were paintings like Gustav Klimt’s 1903 Beechwood Forest, where dense beech trees blot the sky, each leaf captured in one golden brushstroke.‘

Smouldering eroticism pervades all of Gustav Klimt’s artworks. Sometimes flamboyant, at other occasions toned down, but always burning in the shadow. In ‘Beechwood Forest’, Klimt paints trees with sensuality and elegance. He always painted landscape as a means of meditation, usually on holidays spent in Litzlberg at Lake Attersee, enjoying the warm, sunny days with his life companion Emilie Flöge. Klimt approached painting landscapes the same way he painted women, with visible sensuality and liveliness. The absence of people in all of his landscapes suggest that Klimt perceived the landscape as a living being, mystical pantheism was always prevalent. The nature, in all its greenness, freshness and mystery, was a beautiful woman for Klimt.

James Ensor, Skeletons Fighting Over a Hanged Man, 1891

James Ensor, Skeletons Fighting Over a Hanged Man, 1891

James Ensor

‘Stephen Pyle recalled that Syd’s main interests were expressionist artist Chaim Soutine and surrealist painters Salvador Dali and James Ensor. Ensor’s surreal party of clowns with skeletons cropped up in his artwork even thirty years later.‘

Belgian painter James Ensor (1860-1949) was a true innovator of the late 19th century art. He was alone and misunderstood amongst his contemporaries, just like many revolutionary artists are, but he helped in clearing the path for some art movements like Surrealism and Expressions which would turn out to be more popular than Ensor himself. Painting ‘Skeletons Fighting Over a Hanged Man’ is a good example of Ensor’s themes and style of painting: skeletons, puppets, masks and intrigues painted in thick but small brushstrokes, with just a hint of morbidness all found their place in Ensor’s art. There’s no doubt that Barrett was inspired by the twisted whimsicality and playfulness of Ensor’s canvases.

Chaim Soutine, Les Maisons, 1920

Chaim Soutine, Les Maisons, 1920

Soutine

‘Art historian William Shutes noted, ‘Barrett used large single brushstrokes, built up layer by layer, layer over layer, like relief contours.‘

Chaim Soutine was a wilful eccentric, an Eastern Jew, an introvert who left no diaries and only a few letters. But he left a lot of paintings, mostly landscapes that all present us with his bitter visions of the world. He painted in thick, heavy brushstrokes laden with pain, anger, resentment and loneliness. In ‘Les Maisons’ the houses are crooked, elongated, painted in murky earthy colours. Their mood of alienation and instability is ever present in Soutine’s art. He portrayed his depression and psychological instability very eloquently. Description of Barrett’s style of painting, layers and layers of colour, relief brushstrokes, reminds me very much of the way Soutine painted; in heavy brushstrokes, tormented by pain and longings, as if layering colours could release the burden off of his soul.

Rene Magritte, The Son of Man, 1964

Rene Magritte, The Son of Man, 1964

Rene Magritte

There’s no doubt that, as a Surrealist, Magritte was inspirational to young people in the sixties who were inclined to listening to psychedelic music or had a whimsical imagination. With Barrett, Magritte is mostly associated with his ‘Vegetable Man’ phase, in times when his LSD usage was getting out of control, just prior to being kicked out of band. Magritte is, along with Dali, another Surrealist that appealed to Barrett’s imagination. Belgian artist, Magritte meticulously painted similar, everyday objects like men in suits, clouds, pipes, umbrellas and buildings with strange compositions and shadows. In ‘The Son of Man’, some have suggested that he was dealing with the subject of one’s own identity, and that might be something that appealed to Syd when he appeared in the promotional picture with spring onions tied to his head which is an obvious wink to Magritte, not to mention Acimboldo.

Gustave Caillebotte, Les Raboteurs de parquet, 1875

Gustave Caillebotte, Les Raboteurs de parquet, 1875

Gustave Caillebotte

‘Lying in bed one morning, he stared at his blanket’s orange and blue stripes and had a flashback to Gustave Caillebotte’s 1875 painting ‘The Wood Floor Planers’, which depicts workers scraping the wood floors of a sunlit room in striated patterns. Inspired, with Storm Thorgenson’s garish orange and red room at Egerton fresh in his mind, he got up, pushed his few belongings into a corner, and sauntered off to fetch paint from the Earl’s Court Road.‘

This is perhaps Caillebotte’s best legacy – inspiring Syd Barrett to paint his floor in stripes which later ended up gracing his first solo-album, the famously dark and whimsical ‘The Madcap Laughs’, released on 3 January 1970. Like the cover, other pictures taken that spring day in 1969 by Mick Rock and Storm Thorgenson, are all filled with light and have a transcendent mood.

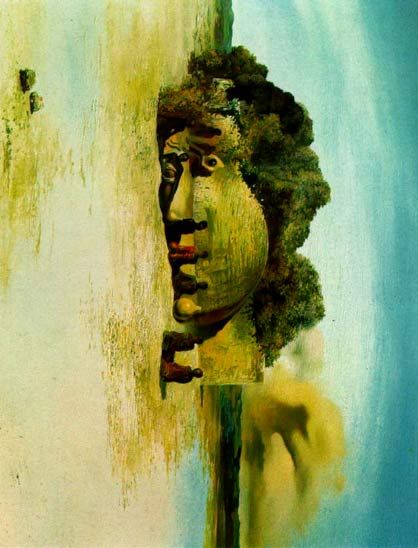

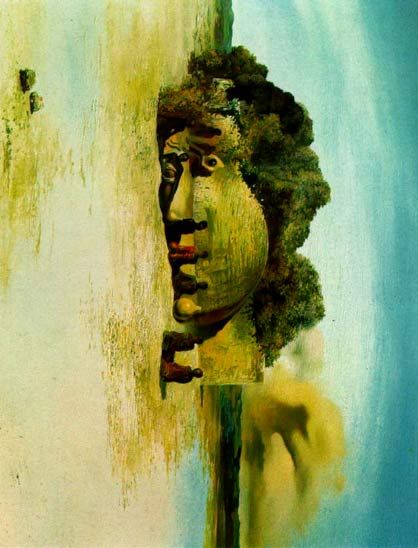

Dali, Paranoiac Visage, 1935

Dali, Paranoiac Visage, 1935

Dali

I believe none of you are surprised that Dali is on this list. Anyone who is familiar with his art will know that it ties very well with the music of Pink Floyd, and perhaps some other psychedelic bands. There’s no one quite like Dali in the world of art. Art he created, like Surrealism in general, is a visual portrayal of Freud’s ideas of the unconscious, and is based on irrationality, dreams, hallucinations and obsessions. His paintings are mostly hallucinogenic landscapes in the realm of dreams; realistic approach combined with deformed figures and objects which, just like in the art of Giorgio de Chirico, evokes feelings of anxiety in the viewer.

When I like an artist, musician or a writer, I always want to know what inspired them, or what they thought of something that I love. What did Barrett really think of Modigliani, for example? But, some things will forever stay a mystery. Perhaps it’s better that way.

Tags: 1960s, 1960s fashion, art, art blog, Chaim Soutine, clowns, Dali, Expressionism, floor, Gustave Caillebotte, Inspiration, James Ensor, Klimt, Modigliani, Painting, Rene Magritte, skeletons, Surrealism, Syd Barrett, Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd: Dark Globe

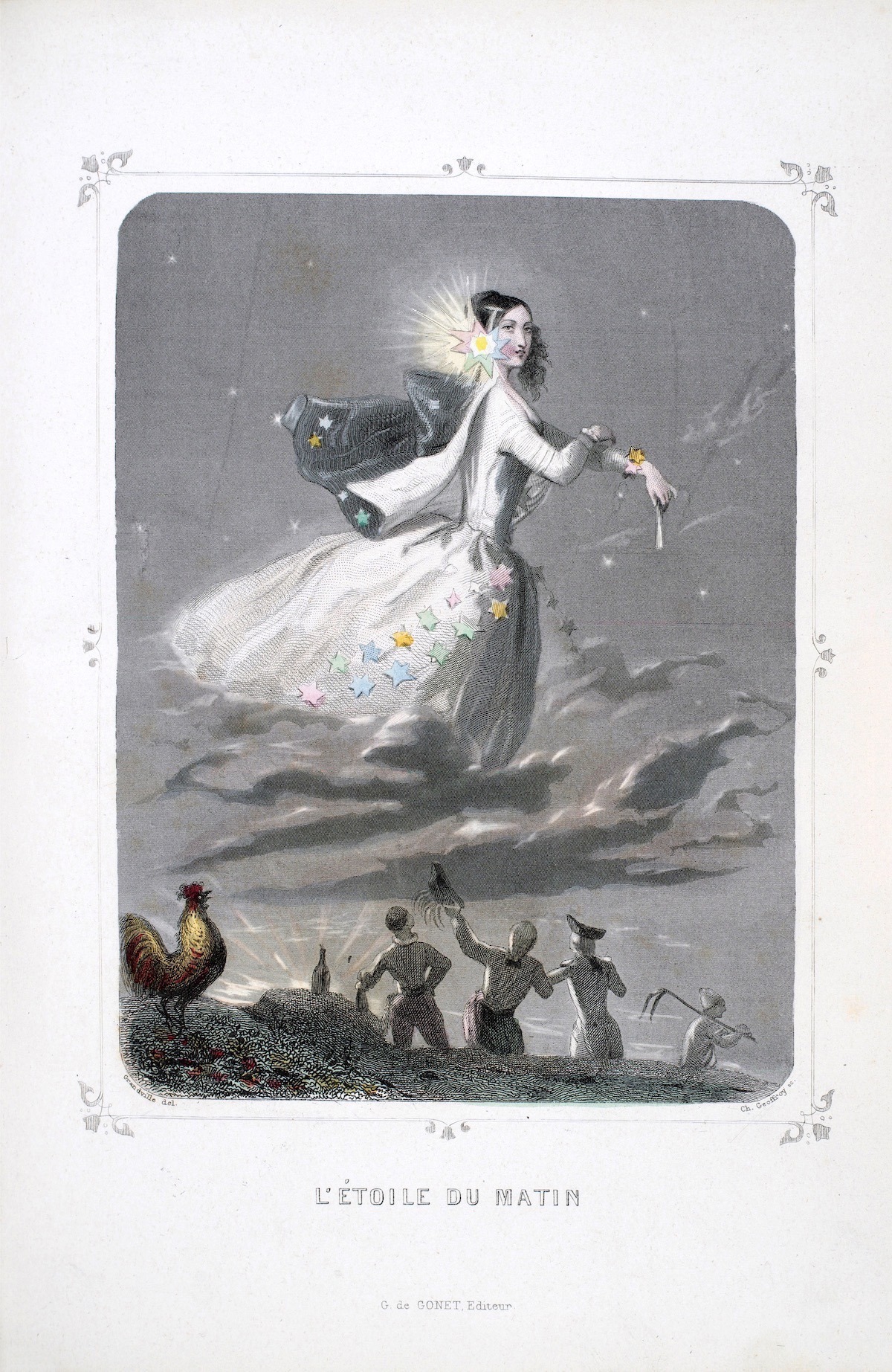

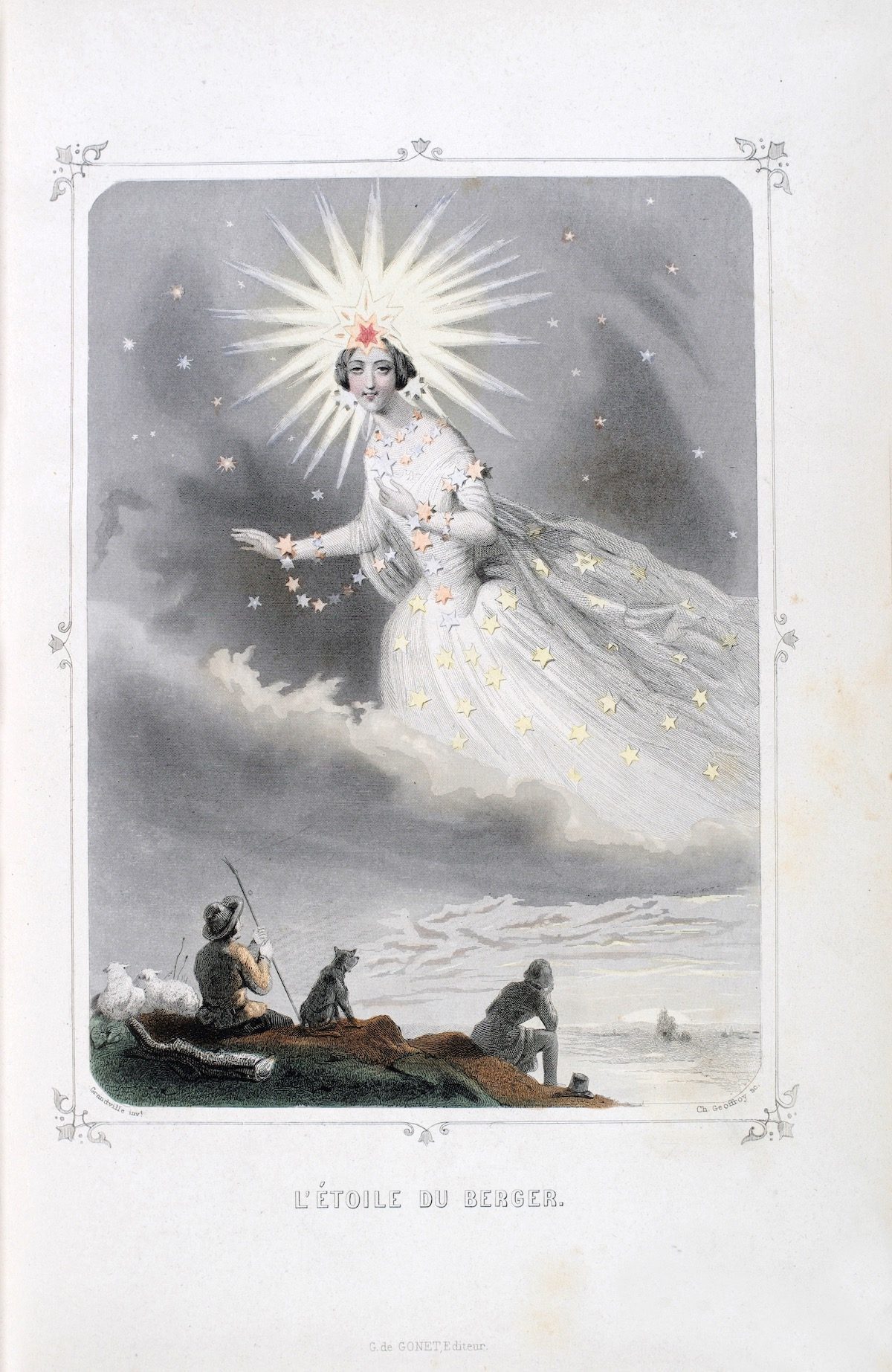

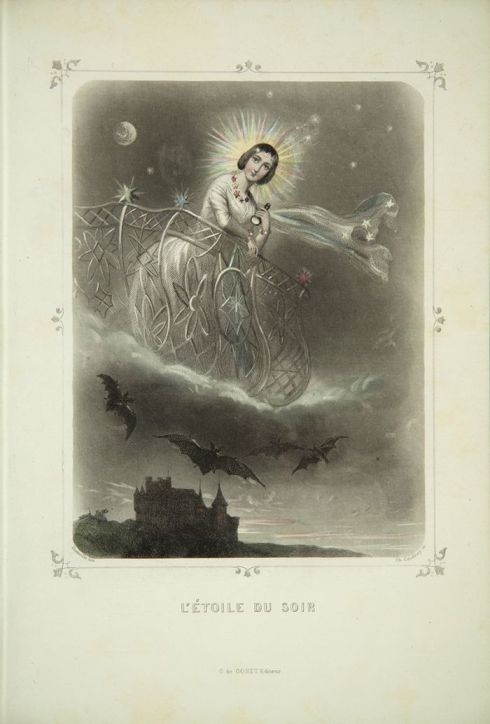

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849