Since the story I am writing is set in the 1840s, I came up with a cunning plan to write a post about women’s fashion at the time! Decade of 1840s represents both the first, and the simplest and most romantic decade of Victorian fashion.

In cultural dimension, the 1840s were a fruitful period for Bronte sisters (1847 in particular), Chopin, Franz Liszt, Edgar Allan Poe, Lord Tennyson, Elizabeth Barrett-Browning, the Pre-Raphaelites, and it also the first decade of applicable photography (Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill were active in this decade).

This is also the the first decade of Victorian era; Queen Victoria married Albert in 1840 and six out of their nine children were born in this decade. Movies set in the 1840s with accurate fashion are: The Young Victoria (2009), Jane Eyre (2011), Effie Gray (2014), La Dame aux Camélias’ (1980), Cranford (TV Series) and Return to Cranford (2009). Costumes in Sweeney Todd (2007) bear resemblance to the 1840s fashion as well.

Fashion in the 1840s represents a muted version of the romantic and flamboyant fashion of the 1830s. Sombre colours and simplicity were in vogue after a decade of exaggeration and flashy colours. The biggest changes in the silhouette occurred in two spheres – firstly, natural waistline came into fashion after more than forty years of high-empire waists, and, secondly, the volume of the sleeves had collapsed.

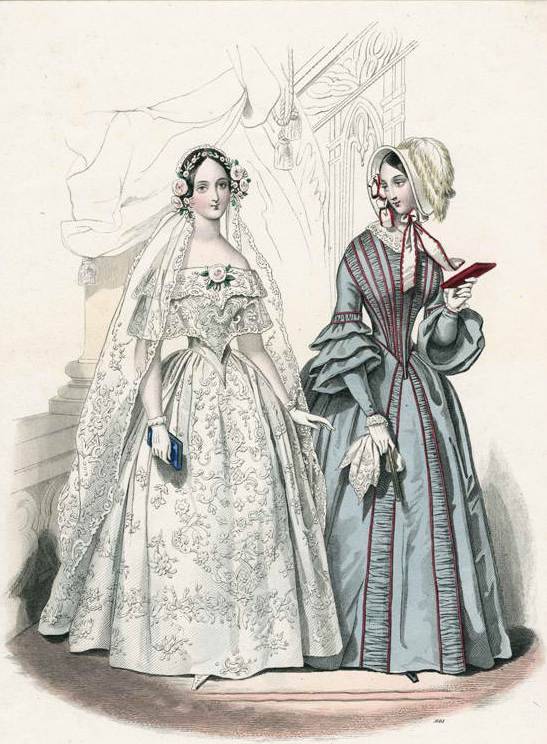

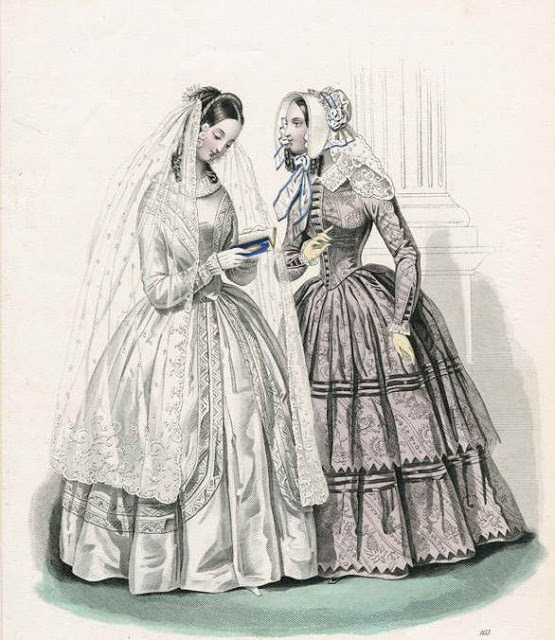

1841. May court fashions (England)

1841. May court fashions (England)

The silhouette of the 1840s was that of a bell shaped skirt, narrow waist and slopping shoulders. Sleeves were tight and simple, without excess decoration, as was the bodice. Skirt was simple as well; bell shaped, sometimes with delicate flounces of lace, but for day wear the appearance was kept modest. The fashionable look of the 1840s could be described as modest, sombre and demure, and, I’d dare to say, a bit gothic, especially with evening dresses, accesorise and details such as black lace, mitts, roses.

In the early years of the decade sleeves still resembled those of the late 1830s; fulness of the sleeves has moved from the shoulder to the lower part of the arm. From about 1843. narrow sleeves were fashionable, and they continued to be so until the late 1850s. Skirts faced changes too; they were gradually becoming wider and wider, richer in flounces and details, and worn with many layers of petticoats to achieve the desirable fulness.

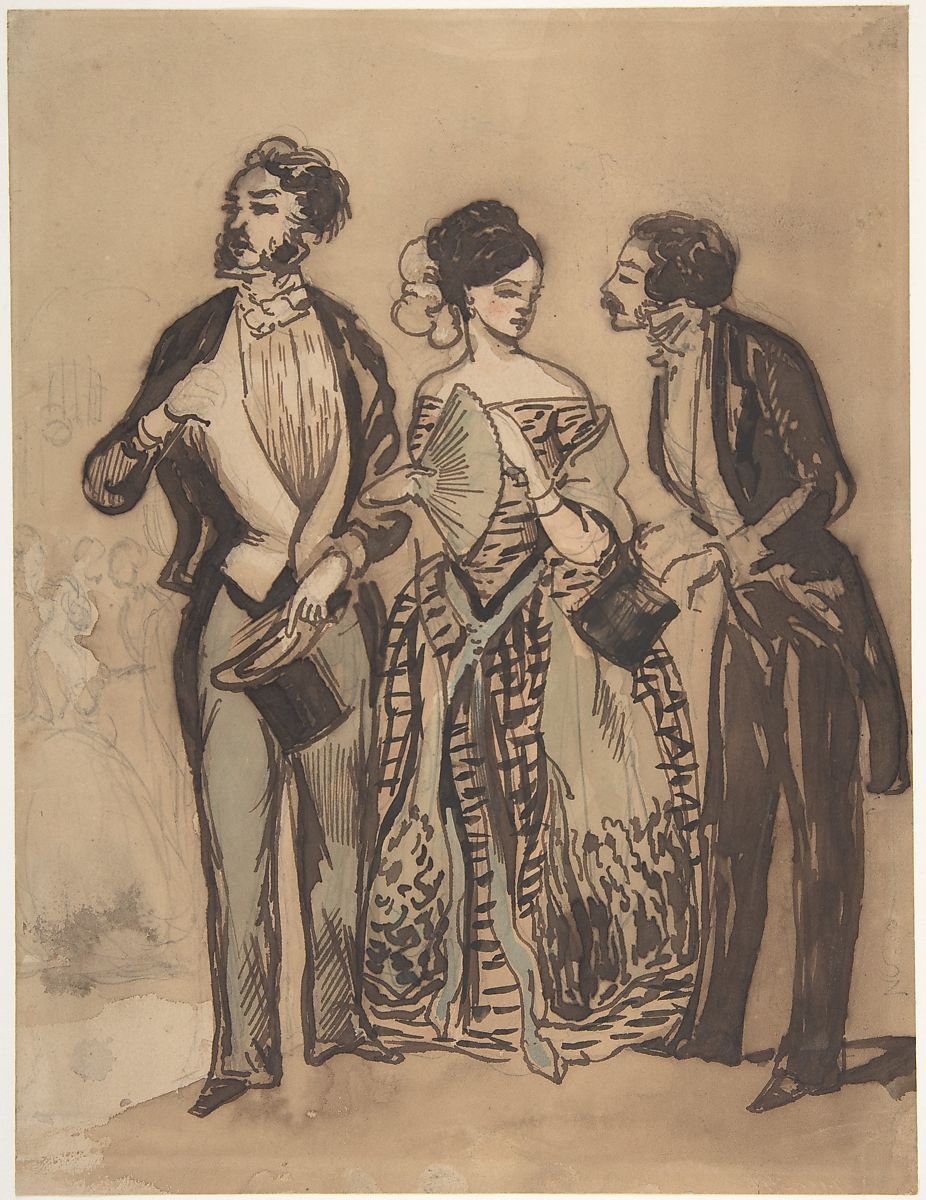

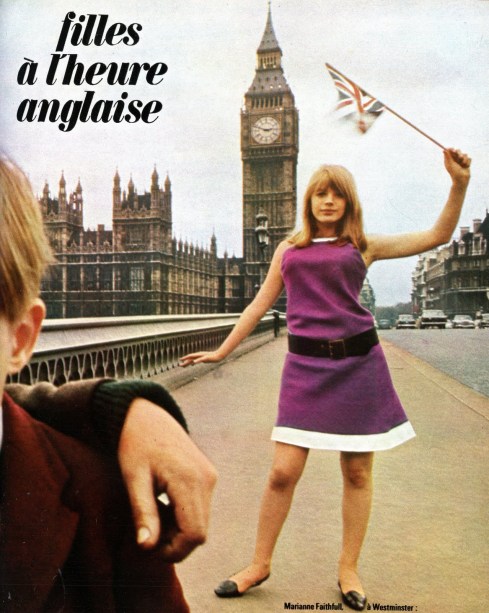

To keep in touch with the overall moderate and dark spirit of the decade, popular colours were rather gloomy and toned down, especially for the day wear. Rich shades were popular for evening dresses, but white was favourable as it symbolised innocence and naivety and was therefor perfect for debutantes. ‘In the 1840’s, soft shades of yellow, greenish gold, blues and pinks were worn; but from the late forties stripes, plaids and the more brilliant shades of blues, greens red, and yellows came into fashion.‘ I have also noticed plaid being a popular fabric for day dresses. As for walking and outdoor dresses, my personal remark is that eggplant purple, cobalt blue and dark greens (darker colours in general) were common, at least judging by the fashion plates.

An interesting and accurate description of colours in Charlotte Bronte’s novel Jane Eyre which was written and set in the 1840s. Blanche Ingram’s evening dress at a small gathering at Thornfield Hall:

‘She was dressed in pure white; an amber-coloured scarf was passed over her shoulder and across her breast, tied at the side, and descending in long, fringed ends below her knee. She wore an amber-coloured flower, too, in her hair: it contrasted well with the jetty mass of her curls.‘ (Chapter 16)

Dresses that Mr Rochester wanted to buy for Jane Eyre:

‘The hour spent at Millcote was a somewhat harassing one to me. Mr. Rochester obliged me to go to a certain silk warehouse: there I was ordered to choose half-a-dozen dresses. (…) I reduced the half-dozen to two: these however, he vowed he would select himself. With anxiety I watched his eye rove over the gay stores: he fixed on a rich silk of the most brilliant amethyst dye, and a superb pink satin. (…) With infinite difficulty, for he was stubborn as a stone, I persuaded him to make an exchange in favour of a sober black satin and pearl-grey silk.’ (Chapter 24)

To balance out the dreariness of the day wear, evening dresses were, although simple in cut, often in rich shades of colours, usually decorated with a deep flounce of black lace and roses – the particular look is evident on many portraits of the time. Evening dresses were worn with lace mitts, opera gloves and sheer shawls which were quite popular during the decade.

Colours that I have noticed being popular for evening or dinner dresses are different shades of green such as lime and emerald green, raspberry pink, lilac, silver grey, sapphire and sky blue, amber and honey yellow. I have also observed that red wasn’t as popular in the 1840s as it shall be in the following decade; if worn, currant and garnet red were favourable.

Hairstyles of the 1840s are rather distinctive; hair was centrally parted and, while the back of the hair was shaped into a bun, front tresses could either be curled tightly or smoothed back over the ears and looped or braided. Compared to the hairstyles of the 1830s, these are quite simple.

Bonnets were toned down too; they became smaller and less extravagant and were decorated only by subtle flowers and tied with ribbons. For evening wear hair was in most cases worn curled and decorated with flowers, and occasionally, by the most fashionable ladies, little turban style caps were also worn.

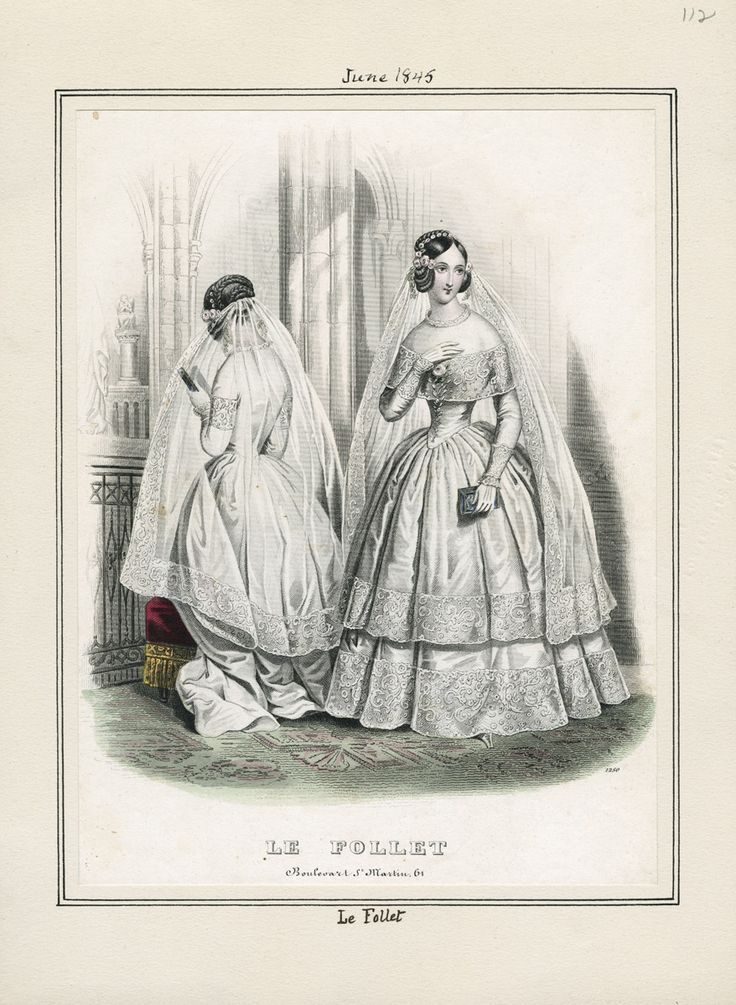

The wedding dresses of this decade are, in my opinion, the most beautiful Victorian wedding dresses. They were worn with long veils, and a dash of lace, with the hair decorated with roses or other small flowers. Queen Victoria married Prince Albert on 10 February 1840, and successfully started a trend for white wedding dresses. However, wearing white for wedding wasn’t as special and new as it seems now; white wedding dresses were worn in the Regency era too as white was the most fashionable colour, and, in addition, white was, as already mentioned, extremely popular choice for evening dresses, especially for young women.

Still, as a Queen, Victoria popularised white for brides and made it a standard colour for wedding dresses, but also strengthened the Ideal of Womanhood. ‘Women were told from all quarters that their job was to stay close to the home and shape the world only through their calm and morally pure influences on the men in their domestic circle.’ Therefore, white colour for wedding dresses was more symbolic than ever. Image of Queen Victoria as an adoring and innocent bride, really captured the public’s imagination and along with the common character of a ‘modest bride in white’ often found Dicken’s novels, she cemented the ideal image of a bride.

Mr Rochester remarked, upon seeing Jane in a white wedding dress and a simple white veil, that she was ‘fair as a lily, and not only the pride of his life, but the desire of his eyes.‘

Queen Victoria described her wedding dress in her journal: ‘I wore a white satin dress, with a deep flounce of Honiton lace, an imitation of an old design. My jewels were my Turkish diamond necklace & earrings & dear Albert’s beautiful sapphire brooch.‘

1839. sketch by Queen Victoria, Design for her bridesmaids dresses

1839. sketch by Queen Victoria, Design for her bridesmaids dresses

Shawl was very fashionable for outwear as it fitted perfectly with the silhouette of sloping shoulders and a bell shaped skirt, and it gives, if I may add, a romantic touch to the outfit. As the sleeves were tight, jackets and coats came into fashion again, but for walking dresses, especially on the north where the Brontës lived, pelerine was both fashionable and practical as it protected the wearer from the strong wind.

As for footwear, 1840s are sadly the last decade of flat shoes. Fashionable shoes for women were satin slippers tied with ribbons around the ankle, and decorated with bows or lace.

That’s it! I sincerely hope that this decade of fashion appealed to you and captivated you as much as it captivated me.

Tags: 1840s, 1840s in fashion, British Fashion, Charlotte Brontë, Colours, evening dresses, fashion, Historical Fashion, Jane Eyre, Queen Victoria, Shoes, Victorian fashion, wedding dresses

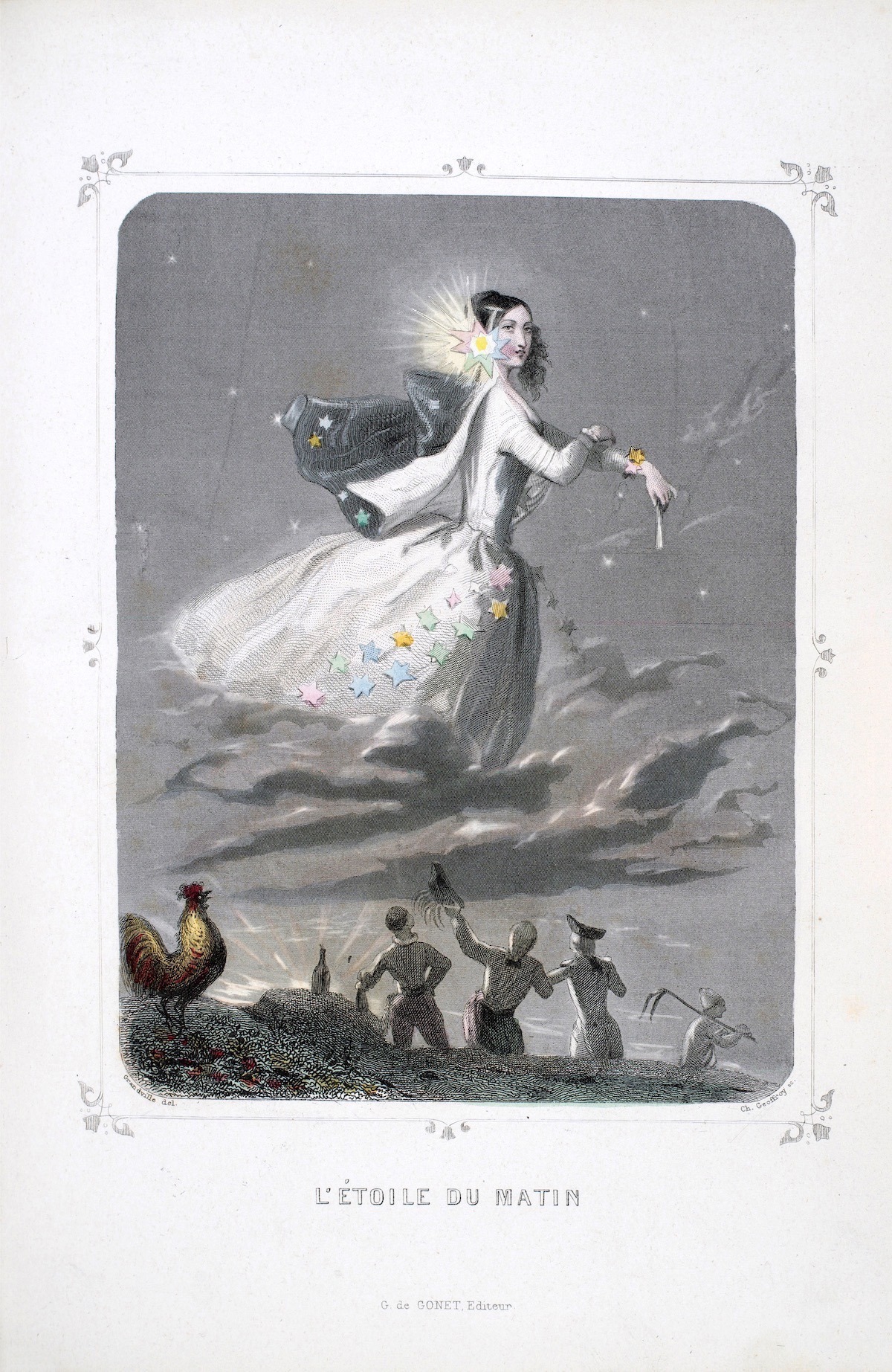

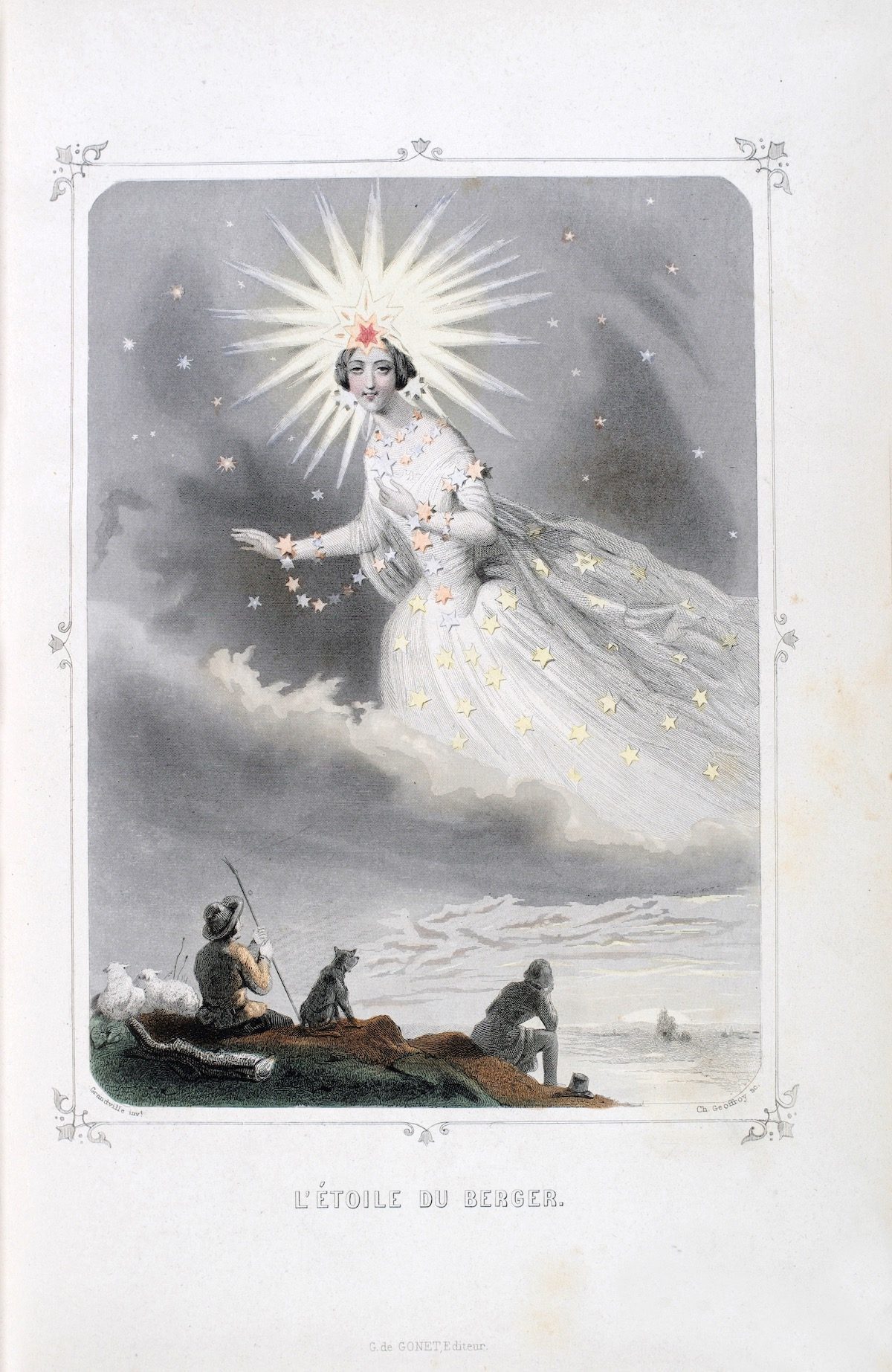

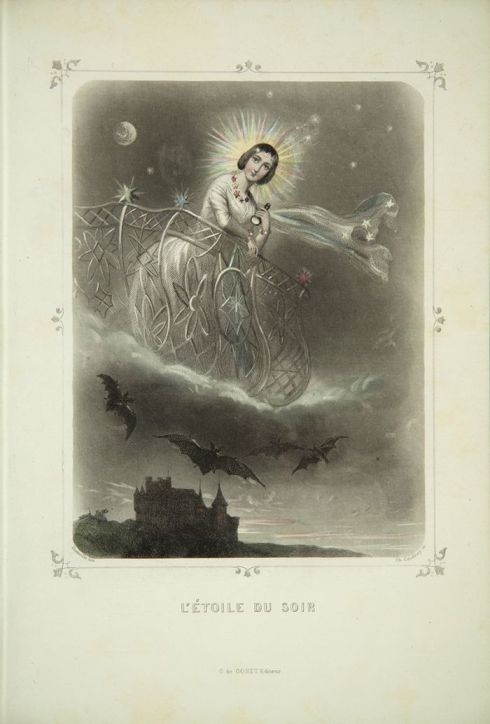

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849

J.J. Grandville, Les étoiles du Soir (Evening Star), 1849