“Those of us who reveal flaws and inconsistencies or voice unpopular ideas suddenly become terrifying to the ones caught up in a world of corporate conformity and censorship that rejects the opinionated and the contrarian, corralling everyone into harmony with somebody else’s notion of an ideal. (…) The greatest crime being perpetrated in this new world is that of stamping out passion and silencing the individual.”

(Bret Easton Ellis, White)

Kazimir Malevich, White on White, 1918

Kazimir Malevich, White on White, 1918

Bret Easton Ellis is an author I’ve loved for years, even though his novels, “American Psycho”, “The Rules of Attraction” and “Less than Zero” to name a few, can be disturbing at times. I am always curious to know what people whose opinions I value have to say on the society at this moment so I was delighted to watch his interview with Rubin Report some time ago on YouTube and even more delighted to read his collection of essays called “White”. As you can imagine, “White” caused outrage and scandal with the mainstream journalists and all the reviews tend to make fun of him or go as far to describe Ellis, who is a liberal gay man, as a sexist racist and/or misogynist, which couldn’t be father from the truth. The reviews focused on their hate for the author rather than reading the essays and seeing them for what they are. The woke journalists who dislike anything apart from their own agenda wrote that “Ellis likes to offend people”, well I personally found nothing to be offended by and I think if you’re offended by someone having an opinion different than yours – then it’s your problem. A quote from Ellis essay “tweeting”: “Social-justice warriors never think like artists; they’re looking only to be offended, not provoked or inspired, and often by nothing at all.”

I especially love hearing Ellis’ views on things today because he, being a Generation X and growing up and living most of his adult life in a pre-instagram and internet world, has a better, broader and more objective perspective, he can observe things from afar but isn’t caught up in them. He often mentions his Millennial generation boyfriend whose views on life and whose reactions he is perpetually perplexed by. That’s not to say that Ellis is just some old man saying things were better in his days, not at all, because everyone who has read his novels will know that he exposes the problems of his generation such as greed, materialism, and alienation. The essay topics range from Ellis’ nostalgic memories of growing up in 1970s Los Angeles (a very different growing up than that of Anthony Kiedis I might say hehe), to films he loved such as American Gigolo and that left impact on him, discovering horror films and porn, interviewing Judd Nelson in the 1980s, to political correctness, Millennial generation’s narcissism, group-thinking and constant whining… It’s a collage of topics for sure, and I really enjoy this casual, direct and honest flow of thoughts. Even thought the critics only saw outrage in Ellis’ essays, he touches on many important things such as free speech, the importance of separating artist from his art, the power of aesthetic over ideology….

And now some quotes:

“This particular wish—the desire to remain a child forever—strikes me as a defining aspect in American life right now: a collective sentiment that imposes itself over the neutrality of facts and context. This narrative is about how we wish the world worked out in contrast to the disappointment that everyday life offers us, and it helps us to shield ourselves from not only the chaos of reality but also from our own personal failures. The sentimental narrative is a take on what Didion meant when she wrote that “we tell ourselves stories in order to live” in her famous essay “The White Album,” from 1979.“

“The overreaction epidemic that’s rampant in our society, as well as the specter of censorship, should not be allowed if we want to function as a free-speech society that believes—or even pretends to— in the First Amendment. (…) By now, just months before the election, it truly felt we were entering into an authoritarian cultural moment fostered by the Left—what had once been my side of the aisle, though I couldn’t even recognize it anymore. How had this happened? It seemed so regressive and grim and childishly unreal, like a dystopian sci-fi movie in which you can express yourself only in some neutered form, a mound, or a clump of flesh and cells, turning away from your gender-based responses to women, to men, to sex, to even looking.”

“Liberalism used to concern itself with freedoms I’d aligned myself with, but during the 2016 campaigns, it finally hardened into a warped authoritarian moral superiority movement that I didn’t want to have anything to do with.”

Things that Ellis writes about the warped authoritarian left is very similar to what Dave Rubin writes in his book “Please Don’t Burn This Book: Thinking for Yourself in an Age of Unreason”:

“(…) the left is now regressive, not progressive. What was once the side of free speech and tolerance—the one that said, “I may disagree with what you say, but I will fight to the death for your right to say it”—now bans speakers from college campuses, “cancels” people if they aren’t up to date on the latest genders, and forces Christians to violate their conscience. They also alienate sensible grown-ups who dislike high taxes, oppose open borders, enjoy the free market, and harbor a healthy distrust of socialism. They’re equally unwelcoming for sane, decent people who happen to be fiscally conservative, classically liberal, libertarian, or—dare I say it—the worst thing of all: straight, white, and male. Rather than being all-inclusive and fair, the left is now authoritarian and puritanical. It has replaced the battle of ideas with a battle of feelings, while trading honesty with outrage.”

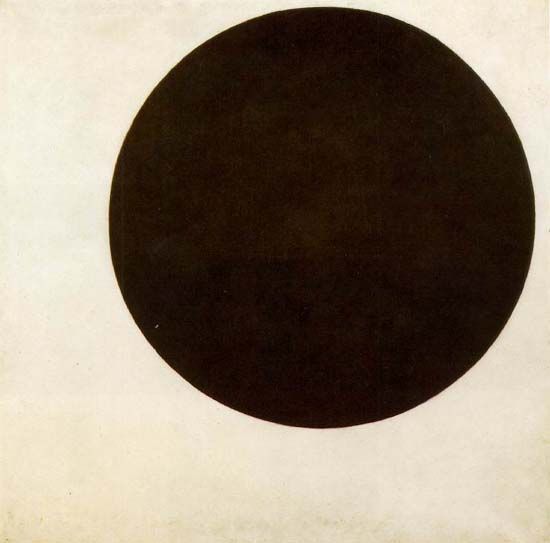

Kazimir Malevich, Black Circle, 1924

And now one more Ellis quote:

“If you feel you’re experiencing “micro-aggressions” when someone asks you where you are from or “Can you help me with my math?” or offers a “God bless you” after you sneeze (…) or the candidate you voted for wasn’t elected, or someone correctly identifies you by your gender, and you consider this a massive societal dis, and it’s triggering you and you need a safe space, then you need to seek professional help. If you’re afflicted by these traumas that occurred years ago, and that is still a part of you years later, then you probably are still sick and in need of treatment. But victimizing oneself is like a drug—it feels so delicious, you get so much attention from people, it does in fact define you, making you feel alive and even important while showing off your supposed wounds, no matter how minor, so people can lick them. Don’t they taste so good?

This widespread epidemic of self-victimization—defining yourself in essence by way of a bad thing, a trauma that happened in the past that you’ve let define you—is actually an illness. It’s something one needs to resolve in order to participate in society, because otherwise one’s not only harming oneself but also seriously annoying family and friends, neighbors and strangers who haven’t victimized themselves. The fact that one can’t listen to a joke or view specific imagery (a painting or even a tweet) and that one might characterize everything as either sexist or racist (whether or not it legitimately is) and therefore harmful and intolerable—ergo nobody else should be able to hear it or view it or tolerate it, either—is a new kind of mania, a psychosis that the culture has been coddling. This delusion encourages people to think that life should be a smooth utopia designed and built for their fragile and exacting sensibilities and in essence encourages them to remain a child forever, living within a fairy tale of good intentions. It’s impossible for a child or an adolescent to move past certain traumas and pain, though not necessarily for an adult. Pain can be useful because it can motivate you and it often provides the building blocks for great writing and music and art. But it seems people no longer want to learn from past traumas by navigating through them and examining them in their context, by striving to understand them, break them down, put them to rest and move on.”

All in all, I think if you love his novels, if you’re interested in Ellis in general or in any of these topics, then there’s a big chance you will enjoy the essays as much as I have!

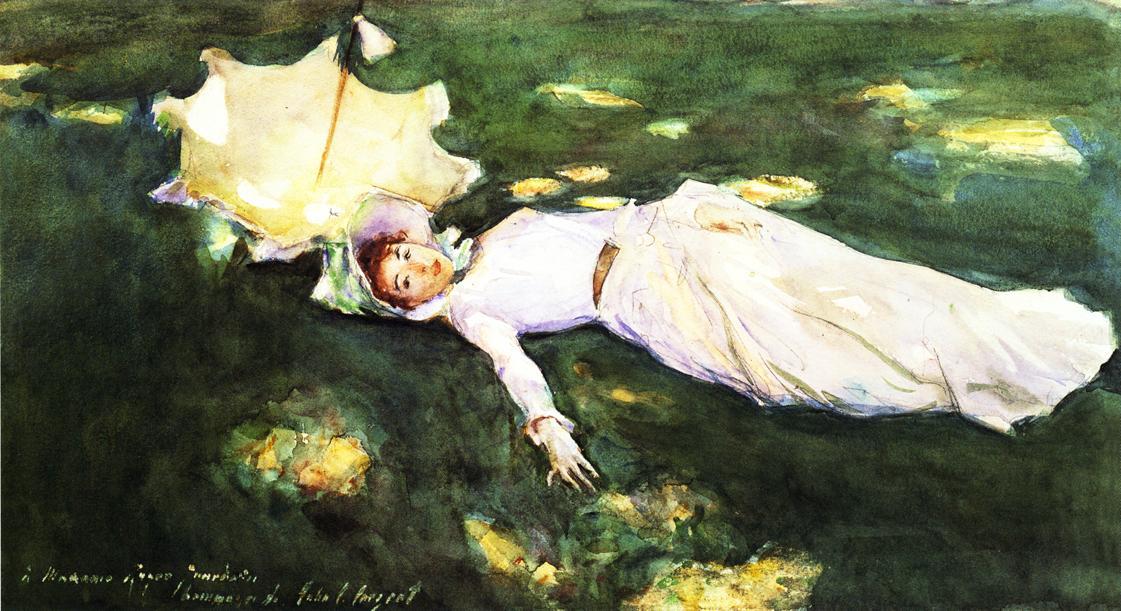

Edward Burne-Jones, Le Chant d Amour (Song of Love), 1869-77

Edward Burne-Jones, Le Chant d Amour (Song of Love), 1869-77

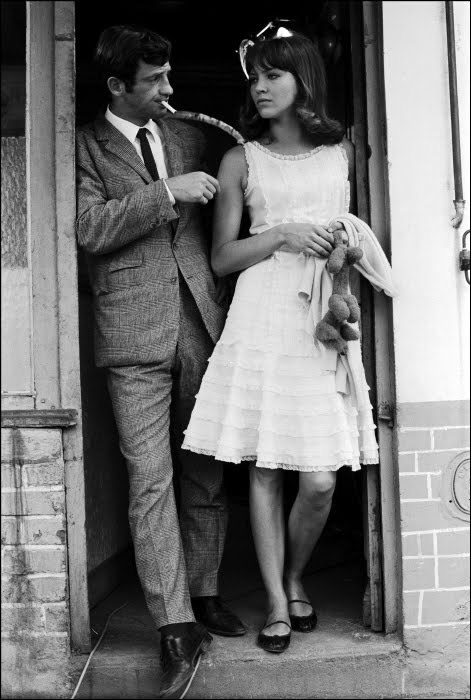

Jane Birkin (1970) and Edwardian lady (1900)

Jane Birkin (1970) and Edwardian lady (1900)

Left: Brigitte Bardot and Right: Nastassja Kinski

Left: Brigitte Bardot and Right: Nastassja Kinski

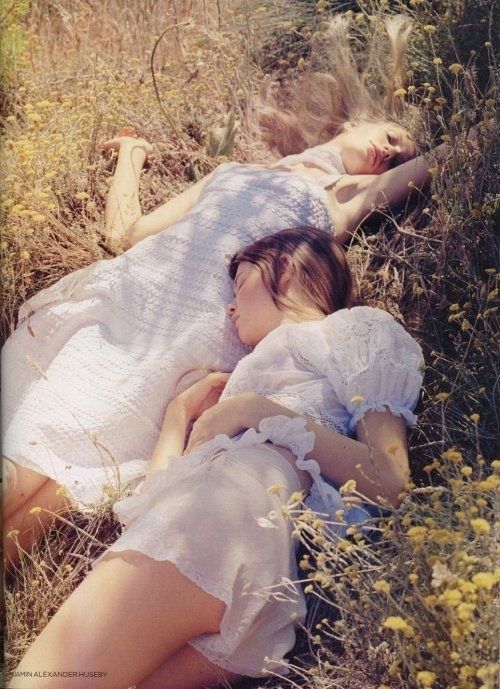

Left: Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Right: two Edwardian ladies, 1900s

Left: Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Right: two Edwardian ladies, 1900s