“Hungary is less frequented by foreign visitors than other great countries of Europe; still, it has charms beyond most In spite of modern development— in many directions—the romantic glamour of bygone times still clings about it, and the fascination of its peoples is peculiar to them.”

(Adrian Stokes, Hungary)

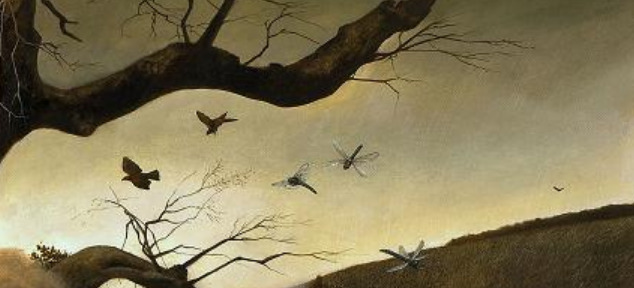

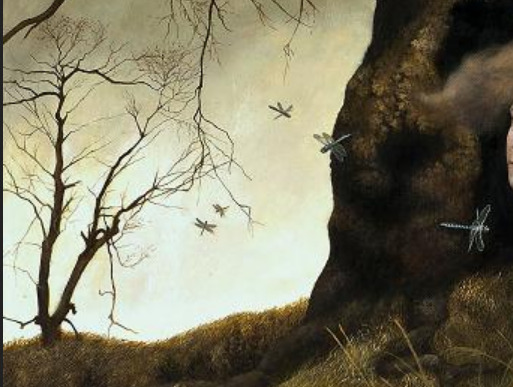

Adrian Stokes, View from our Windows in Vazsecz, 1905-09

Adrian Stokes, View from our Windows in Vazsecz, 1905-09

As I said in my previous post about Marianne Stokes’ paintings of girls in traditional clothes, Adrian and Marianne were a painterly couple who loved to travel and in 1905 their travels took them to Hungary. While Adrian focused mostly on portraying the beauty of the landscapes, small cottages, meadows and poplar trees, his wife Marianne focused on capturing the local people with their interesting faces and vibrant traditional clothes. They returned to Hungary again in 1907 and 1908, and in October of 1909 Adrian published a book about their travels titled simply “Hungary” which is accompanied by the illustrations of both of them. Adrian Stokes’ paintings are not as interesting to me as those of Marianne Stokes because often portraits tend to delight me more than landscapes do, but in this instance, their paintings make a perfect pair because they unite the motifs of peasants and the villages they lived in. Here is a passage from the introduction to Stokes’ book “Hungary” which gives a little background information about the country:

“Various races inhabit the land, but the Magyars — proud, intelligent, and full of vitality—dominate it. The entire population is about 20 millions, of which, approximately, 9 are Magyars ; 5, Slavs ; 3, Rumanians ; 2, Germans ; and 1, various others. Though these races are much interspersed, the richly fertile central plains have become the home of the Magyars ; Slavs occupy outlying parts of the country, and Croatia ; Rumanians, hills and mountains to the east and south-east; Germans, the lower slopes of the great Carpathians, a large part of Transylvania, and the neighbourhood of Styria and Lower Austria. Gipsies and Jews are to be met with nearly everywhere. The landscape is of great variety. Vast plains, bathed in hazy sunlight, where great rivers glide on their way to the East ; wooded hills and rushing streams ; lovely lakes ; sombre forests, from which grim mountains rear their huge grey shoulders in the clear air, are all to be found; and dotted about may be seen figures that recall the illustrations in an old-world Bible.”

Adrian Stokes, Rumanian Cottages in Transylvania, c 1909

I enjoyed Adrian’s impressions of the travel perhaps even more than I enjoyed the paintings themselves. His writing is very poetic and he is observant for details and the world around him, both nature and interesting people. Travel from Transylvania to Tátra:

“It was a long and tedious railway journey, lasting all one night and half the next day. I remember moonlit rivers and little whitewashed cots with tall thatched roofs, dark as sealskin, and here and there an orange light in a window, and, behind all, deeptoned mountains and the stars. A friendly fellow-passenger told us when we at last entered the Tatra, winding our way among hills richly wooded with beech and oak. We had passed Kassa and its beautiful Gothic church, and went on to Tatra Lomnicz, changing at Poprad, whence one can drive to the wondrous ice-caves of Dobschauer ; but, unfortunately, we did not do so. It was near Poprad that we had our first view of the mighty central range of Carpathians, rising grim and grey from a level plain. They stretch from east to west for about thirty miles, and lesser chains continue, or run parallel with them. (…)

In the Tatra the air is fresh and invigorating. Clearly defined clouds move across blue skies by day, and at sunset the great mountain formations stand sharply silhouetted against an intense light. The scent of pines is everywhere. To many of us pine-forests, with their long serrated edges, and individual trees, each very much resembling the rest, are at first unsympathetic, but by the dwellers in Central and Southern Europe they are beloved. For them they mean health and holidays. As the seaside and salt sea-breezes have from childhood been to us, so for them are pine-clad slopes and the delicious air of mountain regions.”

Adrian Stokes, The Carpathian Mountains from Lucsivna-Fürdő, c 1905-1909

It is interesting how Adrian Stokes saw the nature and especially woods beneath the Carpathian Mountains as wild, untainted by civilisation; a primal heaven lost in the west, while at the same time people who lived there and experienced its isolation and harsh living conditions scarcely felt that mystical flair. Czech writer Karel Čapek’s novel “Hordubal” (1933), for example, is set in Carpathian Ruthenia and reading the novel you feel that apart from drinking there is absolutely nothing to do there because it’s such a desolate and poor area, far away from anything interesting or fun. These tall birches in Stokes’ painting above look awe inspiring and dreamy and in his book he explains the name “fürdő”:

“The Hungarian word fürdő —meaning bath — seems to occur here of itself. It is usually affixed to the names of watering-places, as in Lucsivnafiirdo, a place near birch-woods, which we had seen from the train and decided to visit. We went one morning, and liked it so well that we made arrangements to stay there on leaving Vazsecz. But that was not yet to be.”

Adrian Stokes, Menguszfalva, 1905-1909

Adrian Stokes, Harvest Time in Transylvania, c 1905-1909

Adrian Stokes, Haytime, Upper Hungary, c 1905-1909

Marianne Stokes, A Cottage at Zsdjar, 1905-1909

Tags: 1900s, 1905., 1909, 20th century art, Adrian Stokes, art, Austro-Hungarian Empire, cottage, countryside, Hungary, Landscape, Marianne Stokes, meadow, Painting, Transylvania, village

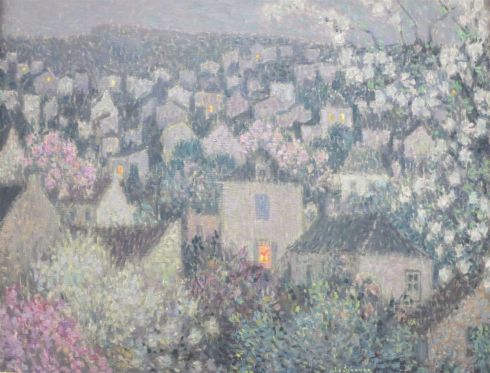

Henri le Sidaner, Soir de Printemps, c. 1920

Henri le Sidaner, Soir de Printemps, c. 1920