Egon Schiele died on the 31st October 1918. Three days prior to that he witnessed the death of his pregnant wife Edith. If it wasn’t for the Spanish influenza, she could have had their child and his prodigious mind could have produced many more drawings and paintings.

Egon Schiele, Death and the Maiden, 1915

Egon Schiele, Death and the Maiden, 1915

Painting “Death and the Maiden” is a very personal work and it connects and unites two themes that were a lifelong fascination to Egon Schiele; death and eroticism. It shows two figures in an embrace, apparently seen from above, not unusual at all for Schiele to use such a strange perspective. They cling to each other in despair; painfully aware of the finality and hopelessness of their love. They are lying on rumpled white sheets, their last abode before the hours of love vanish forever, which simultaneously add a touch of macabre sensuality and remind us of the burial shroud. The background is an unidentifiable space, a desolate landscape painted in colours of mud and rust.

Death is a man not so dissimilar to Schiele’s other male figures or self-portraits, without the help of the title we couldn’t even guess that is represents death. The red-haired woman hugs him tightly with her long arms and lays her head on his chest. She is not the least bit afraid of his black shroud of infinity. She holds onto him as if he were love itself, and still, her hands are not resting on his back gently, they are separate and her crooked fingers are touching themselves. We can sense their inevitable separation through their gestures and face expressions, and, at the same time, their embrace feels frozen in time, the figures feel stiff and motionless, as if the rigor mortis had already taken place and bound them in an everlasting embrace. The maiden will not die, she will be clinging to death for all eternity.

It is impossible not to draw parallels between the figures in the painting and Schiele’s personal life at the time. The figure of Death resembles Schiele, and we do all know he showed no hesitation when it came to painting and even taking a photo of himself, and the red-haired woman is then clearly Wally. To get a better perspective at the symbolism behind this painting, we need to understand the things that happened in Schiele’s life that year. In June 1915 he married Edith Harms; a shy and innocent girl next door. But first he needed to brake things off with Wally Neuzil, a lover and a muse who not only supported him during the infamous Neulengbach Affair but was also, ironically, an accomplice in introducing him to Edith.

Upon meeting Wally for what was to be the last time, Egon handed her a letter in which he proposed they spend a holiday together every summer, without Edith. It’s something that Wally couldn’t agree with. Perhaps she wasn’t a suitable woman to be his wife, but she wasn’t without standards or heart either. There, in the dreamy smoke of Egon’s cigarette, sitting at a little table in the Café Eichberger where he often came to play billiards, the two doomed lovers bid their farewells. Egon gazed at her with his dark eyes and said not a word. He was disappointed but did not appear particularly heart-broken, at least no at first sight, but surely the separation must have pained him in the moments of solitude and contemplation, the moments which gave birth to paintings such as this one.

Egon Schiele, Embrace, 1915

If we assume then that the painting indeed shows Egon and Wally, the question arises: why did he chose to portray himself as a personification of Death? He chose to end things with Wally, so why mourn for the ending? And shouldn’t Death be a possessive and remorseless figure who smothers the poor delicate Maiden in his cold deadly embrace? Schiele’s embrace in the painting seems caring and his gaze full of sadness.

On a visual level, the motif of two lovers set against a decorative background brings to mind both Gustav Klimt’s “The Kiss” (1907) and Oskar Kokoschka’s “The Bride of the Wind (or The Tempest)” from 1914. Although similar in composition, the mood of Schiele’s painting differs vastly to those of his fellow Viennese eccentrics. Klimt’s painting shows a couple in a kiss and oozes sensuality and beauty, the background being very vibrant and ornamental. It’s a painting made before the war, its horrors and changes. Kokoschka’s painting is, in a way, more similar to Schiele’s but they two are very different in the overall effect. Both show doomed lovers in a sad embrace, and a strange, slightly distorted background, but Kokoschka’s painting is a whirlwind of energy, brushstrokes are nervous and energetic, the space is vibrant, not breathing but screaming. Schiele’s painting exhibits stillness, stiffness, a change caught in the moment, a breeze stopped, and the space around them seems heavy, muddy and static. “Kokoschka’s is a ‘baroque’ painting, while Schiele’s relates more to the Gothic tradition. “The Tempest” is life-affirming, the Schiele is resigned to the inevitable, immobile and drained of life.” (Whitford; Egon Schiele)

Egon Schiele, Lovemaking, 1915

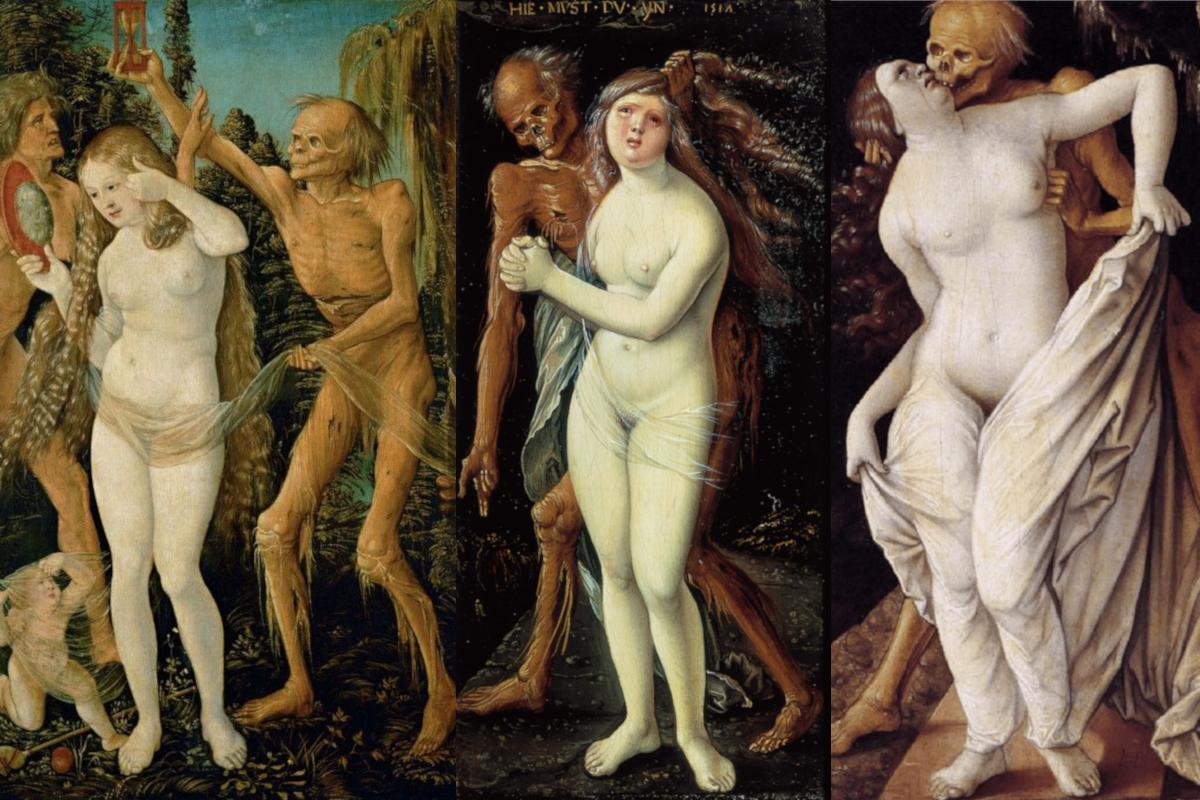

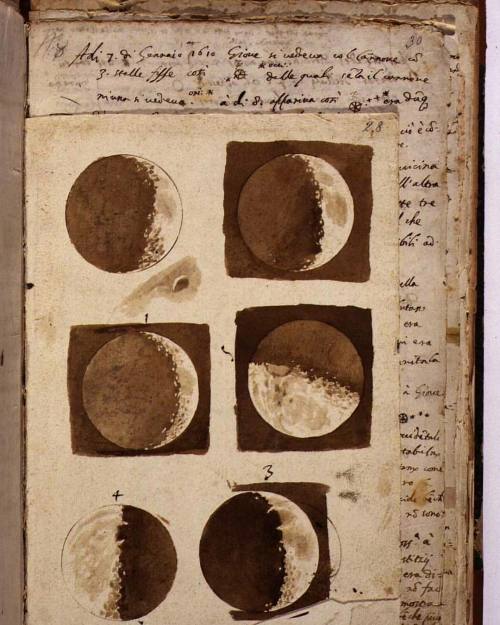

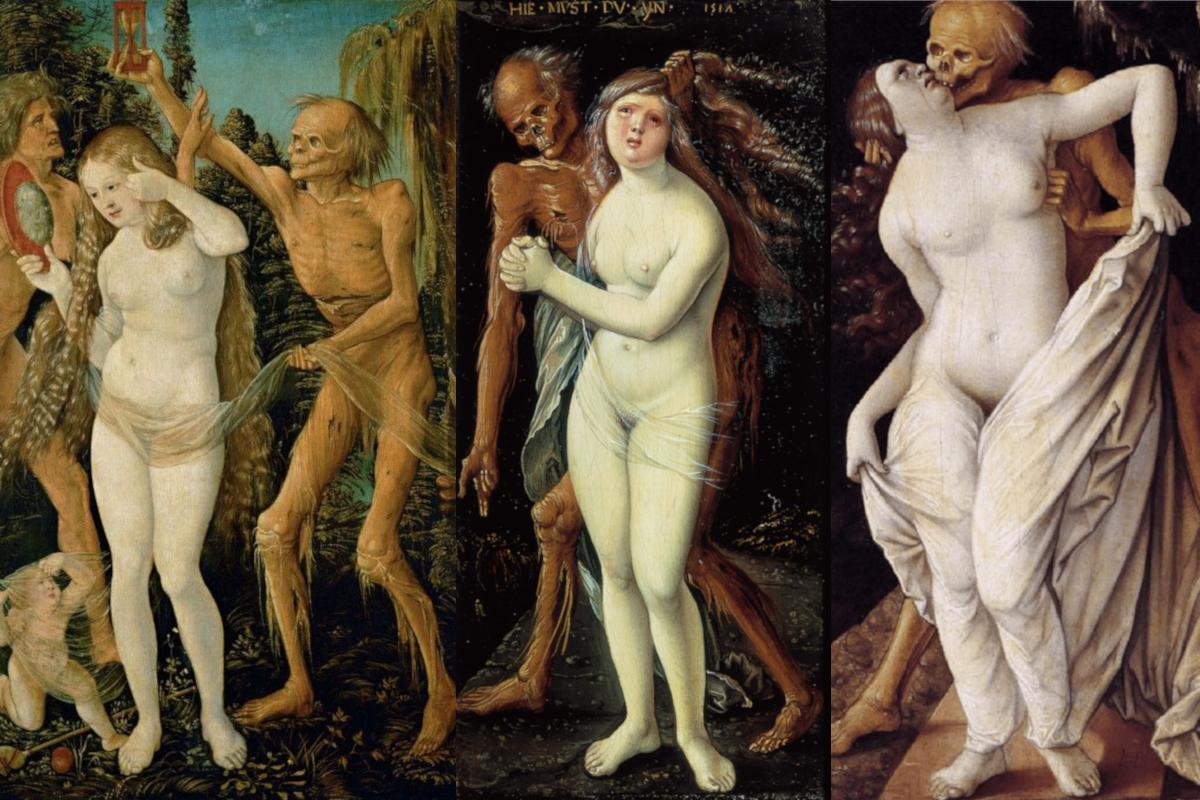

In this painting Schiele used the old theme of Death and the Maiden and enriched it by adding an introspective, private psychological dimension. Schiele’s rendition of the theme isn’t a meditation on transience and vanity as it was in the works of Renaissance masters such as Hans Baldung Grien; a gifted and imaginative German painter and a pupil of Albrecht Dürer. Grien revisited the theme of Death and the Maiden a few times during a single decade, at the beginning of the sixteenth century. These paintings always feature a beautiful and something vain young woman (she is looking at herself in the mirror) with smooth pale skin and long golden hair, and a grotesque figure of Death looming behind her like a shadow, reminding her with a sand clock that soon enough she too will come into his arms.

Hans Baldung Grien, from left to right: Death and the Maiden, 1510; Death and the Maiden, 1517; Death and the Maiden, 1518-20

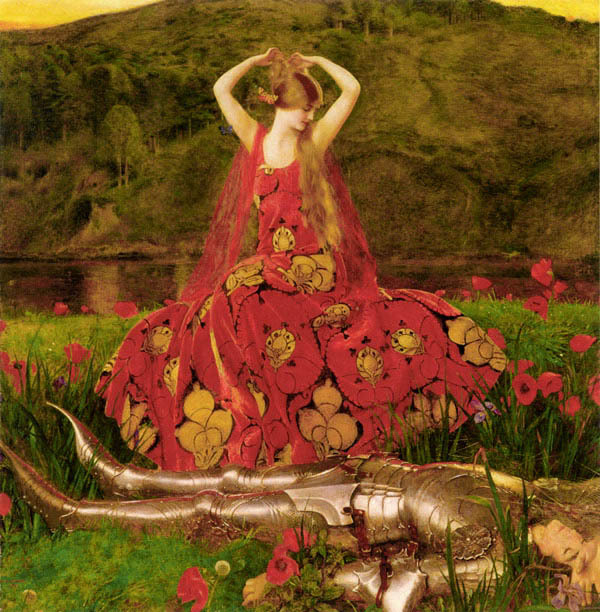

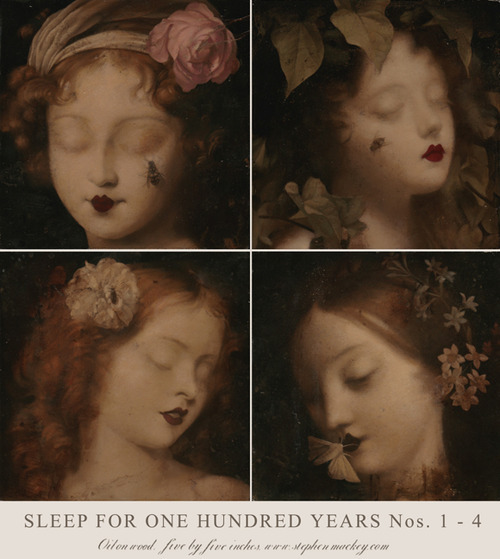

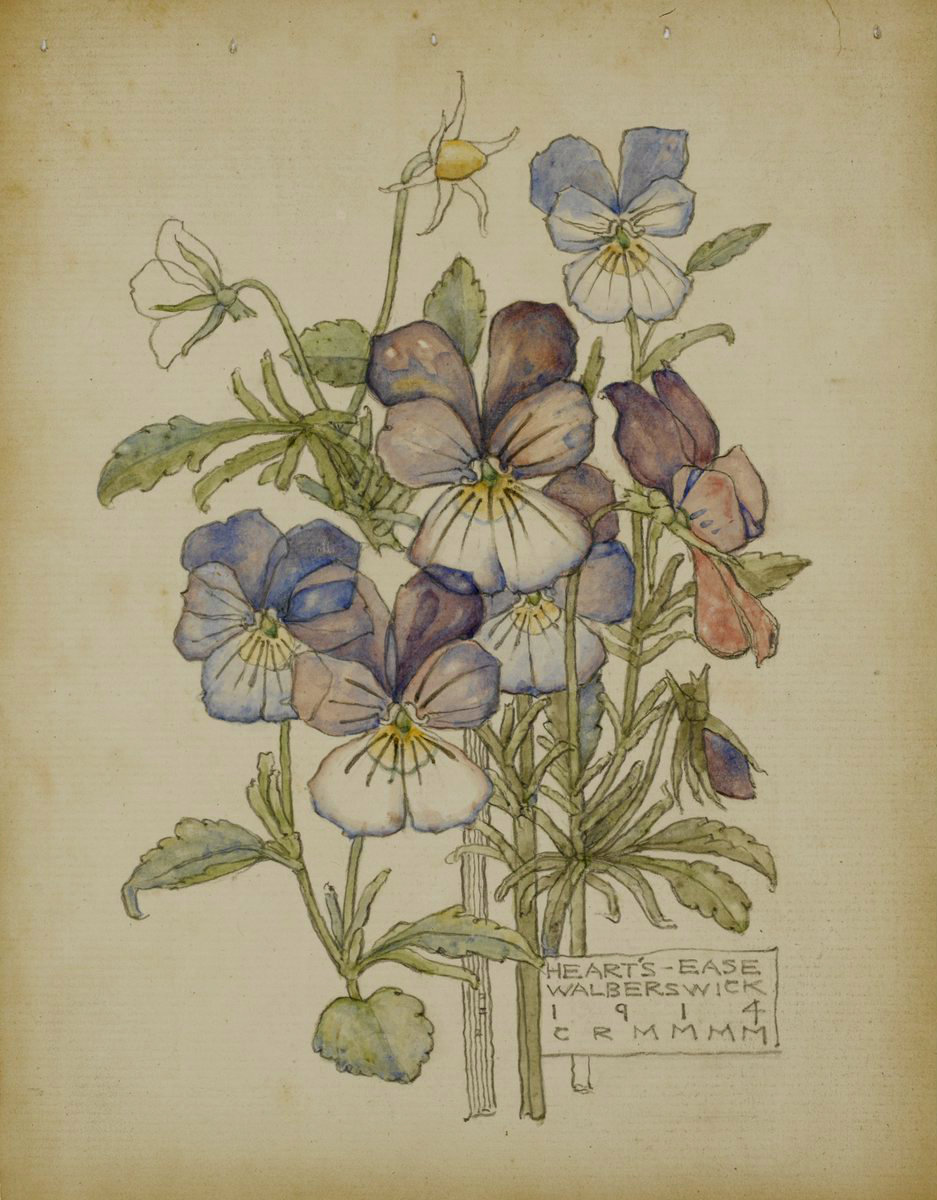

I’ve included two more examples of this theme in this post; another version by Grien where Death is shown chowing the Maiden’s dress and the knight is literally saving his damsel not from the dragon or from danger, but from Death and mortality itself. Quite cool! And an interesting detail from Van Groningen’s “The Triumph of Death” where Death is shown as a skeleton in a cloud armed with a spear, chasing a frightened and screaming young Maiden dressed in flimsy robes who is running around hopelessly trying to escape. In these paintings, the Maiden is merely a symbol of the fragility of youth and beauty, but later artists, the Romantics and the fin-de-siecle generation, and Schiele too, had different vision of Death; they glamorised it and romanticised it. In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story “Edward Fane’s Rosebud” the beautiful young Maiden Rose is faced with mortality for the first time and how poetically Hawthorne had described it:

“She shuddered at the fantasy, that, in grasping the child’s cold fingers, her virgin hand had exchanged a first greeting with mortality, and could never lose the earthly taint. How many a greeting since! But as yet, she was a fair young girl, with the dewdrops of fresh feeling in her bosom; and instead of Rose, which seemed too mature a name for her half-opened beauty, her lover called her Rosebud.”

Death was a life-long fascination for Schiele; at a very young age he witnessed his father’s madness and suffering death, possibly from syphilis, he was obsessed with the idea of doppelgänger who was seen as a foreboding of death, in his poem “Pineforest” he even wrote “How good! – Everything is living dead”. All his art is tinged with death, and with Schiele it wasn’t a fad of the times but a deep, personal morbid obsession. In the height of summer, he already senses autumn leaves, in the living flesh he already sees decay. Also, he was born in 1890, and along with other artists of his generation he witnessed the final decay of a vast empire that had lasted for centuries; “Decay, death and disaster seemed to haunt their every waking hour and to provide the substance of their nightmares.” (Whitford, Egon Schiele)

Hans Baldung Grien, The Maiden, the Knight and Death, date unknown

Jan Swart van Groningen, Der Triumph des Todes (detail), 1525-50

Life and Death contrafted or, An Essay on Woman, 1770

Richard Bergh, The Girl and Death, 1888

Henry Levi (1840-1904), La jeune fille et la mort, 1900

Marianne Stokes, The Young Girl and Death, 1900

Happy Halloween, with Schiele and Death!

Tags: 1915, Beauty, dead, Death, Death and the Maiden, death anniversary, Egon Schiele, erotic, Hans Baldung Grien, love, Maiden, Oskar Kokoschka, Sadness, Schiele, Separation, The Tempest, transience, Vienna, Wally Neuzil, young girl

Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Clara the Rhinoceros, 1749, oil on canvas, 310×456 cm

Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Clara the Rhinoceros, 1749, oil on canvas, 310×456 cm