“My life is cold, and dark, and dreary;

It rains, and the wind is never weary;

My thoughts still cling to the moldering Past,

But the hopes of youth fall thick in the blast,

And the days are dark and dreary.

Be still, sad heart! and cease repining;

Behind the clouds is the sun still shining;

Thy fate is the common fate of all,

Into each life some rain must fall,

Some days must be dark and dreary.”

(Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Rainy Day)

Maurice Prendergast, Ladies in the Rain, 1894

Maurice Prendergast, Ladies in the Rain, 1894

In this post I wanted to make a little selection of some lovely rainy day scenes in art, mostly from the nineteenth and early twentieth century art. The first painting of my selection is a dazzling watercolour by the American painter Maurice Prendergast which shows two ladies strolling in the rain. The watercolour has a distinct vertically elongated shape which gives the painting a touch of Japonisme and this shape fits the scene perfectly because it provides space for the two figures of the ladies descending small stairs in some park and for a tree in the background. The colour of their dresses fits the overall mood of the rainy day and yet Prendergast manages to make even the dark blues, black and greys so fun and exciting.

John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud (Rainstorm over the Sea) (1824-28), oil on paper

Constable’s seascape study “Rainstorm Over the Sea” painted between 1824 and 1828 is a long time favourite of mine. It shows a beach in Brighton in rainy, stormy weather. I love how dramatic and spontaneous the painted clouds are, so mad and so full of rain, ready to pour down all over the beach pebbles and the sea. Interestingly, the sea takes up little space on the canvas while the sky dominates the scene and rightfully so because that is where the sublime moment of nature, the rainstorm, is occuring.

Childe Hassam, Rainy Midnight, 1890

Again we have Childe Hassam who seems to have enjoying portraying rain scenes in urban environment, as you may have seen in my last post about his gorgeous watercolour “Nocturne, Railways Crossing, Chicago” (1893). The streetscene is a blurry harmony of blues from the rain and pale yellow of the streetlamps and the only motif here is a carriage by the side of the road; is it waiting for a rich party-goer to leave the party at midnight, or is it already carrying their drunken passangers home after a ball or a theatre evening? Whatever the situation, Hassam creates a stunning play or blues and yellow and paints the excitement of the night life in a big city, even in rainy weather.

Henri Riviere, Funeral Under Umbrellas, 1895, etching

I already wrote a long post about this etching here. In short, what I love about this etching is its strong influence of the Japanese ukiyo-e prints which reveals itself in the diagonal composition, the flatness of the figures and the way the rain, carried by the strong wind, is painted in many thin lines that indicate the direction of it.

Childe Hassam, A Rainy Day in New York City, c 1890s

Another painting by Hassam! “A Rainy Day in New York City” shows an elegant lady dressed in a yellow-beige gown rushing home because of the rain. She has an umbrella, but still she must lift her dress to avoid the puddles. And how will the damp weather affect her hairstyle, ahh…. so many troubles! Her little black boots are stepping on the pavement glistening in blues, yellow and oranges, the puddles reflecting the big city lights. Again, we have the vertically shaped canvas and the figure of the woman is cut-off a little bit, both reveal the influence of Japonisme.

Pierre-August Renoir, Umbrellas, 1883

Renoir’s painting “Umbrellas” always brings to mind the video of the song “Motorcycle Emptiness” by the Welsh band Manic Street Preachers. The video was short in Tokyo in 1992 and in many scenes people are seen walking down the street in the rain, many colourful umbrellas filling the horizon. For some reason, Renoir’s street scene, almost cluttered with umbrellas, not so colourful though but mostly blue and black, always brings to mind that video and the music which matches the sadness of the rain.

Childe Hassam, Rainy Day, 1890

Another fun rainy day scene by the American painter Childe Hassam called simply “Rainy Day”, painted in 1890. The effect of rain is beautifully captured here and the composition is very interesting. The house on the right is visible, but the church with its tall tower in the background on the left is shrouded in the mist. People are rushing down the street, eager to get home fast and escape the rain, notably the two figures of ladies with their umbrellas, which remind me of the ladies in Prendergast’s watercolour.

Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947), Rue Tholozé (Montmartre in the Rain), 1897

Bonnard’s painting “Montmartre in Rain”, painted at the very end of the nineteenth century, shows a different view of the rain. Here the rain is seen through the window, and it isn’t a grey and dreary rendition of the rain scene but rather the scene shows the beauty of a rainy night when the yellow light of the lanterns is reflected in the wet pavements dotted with puddles. Black figures with black umbrellas are strolling around and everything is lively and magical.

Otto Pippel (German, 1878-1960), Street in rainy weather, Dresden, 1928

German painter Otto Pippel shows us a chaotic rainy day scene in his painting “Street in Rainy Weather, Dresden”, painted in 1928. At first sight the painting is a mess of greys and blues because Pippel painted the scene as if it was seen though a window covered in rain drops and this is really interesting. Everything; buildings, streets, street lamps and people, are painted in a blurry, vague manner.

Sir Muirhead Bone, Rainy Night in Rome, 1913, drypoint

Sir Muirhead Bone’s drypoint “Rainy Night in Rome”, painted in 1913, shows the people leaving the church, I assume after the evening mass. There are rushing with their umbrellas and there is even a carriage waiting for someone too rich to experience a walk in rain. The vertical form of the drypoint where the upper half show the sky and the church and the bottom part shows the church entrance, the street and the people, is great because it shows the flow of the rain, painted in vertical lines.

Tags: 1894, 1913, 19th century art, art, art blog, Childe Hassam, drypoint, English art, French Art, Funeral Under Umbrellas, Henri Riviere, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Impressionism, John Constable, Ladies in the Rain, Manic Street Preachers, Maurice Prendergast, Rain, rain in art, rainstorm, Rainy Midnight, Rainy Night in Rome, Renoir, Romanticism, Sea, Sir Muirhead Bone, Street in Rain, Street Scene, The Rainy Day, thunder, umbrella

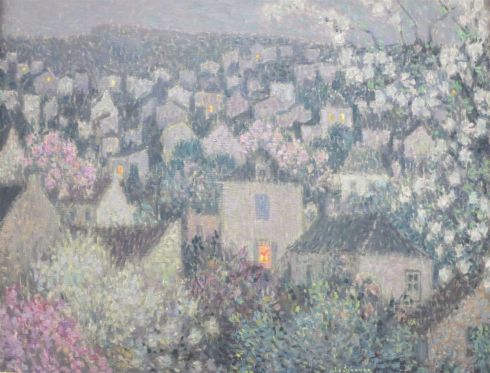

Henri le Sidaner, Soir de Printemps, c. 1920

Henri le Sidaner, Soir de Printemps, c. 1920

Edgar Degas, Waiting for a Client, 1879, charcoal and pastel over monotype on paper

Edgar Degas, Waiting for a Client, 1879, charcoal and pastel over monotype on paper