“The passion of lovers is for death said she

Licked her lips

And turned to feather”

(Bauhaus, The Passion of Lovers)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Gianciotto Discovers Paolo and Francesca, 1819

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Gianciotto Discovers Paolo and Francesca, 1819

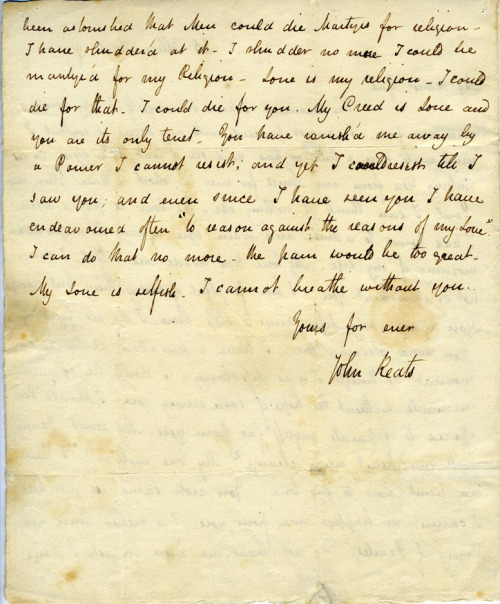

Kisses

It is easy to envelop the distant, mythical past in many veils of dreams and poetry. Romantics loved romanticising and the subject of doomed thirteen century lovers which charmingly unites the themes of love and death, was a perfect fuel for the artists’ fantasies from Ingres all up to now probably. Even the embraced couple, carved in splendid white marble, in Auguste Rodin’s sculpture “The Kiss” shows Paolo and Francesco, though the title of the work wouldn’t reveal it instantly. Different artists chose to portray different moment in Paolo and Francesca’s doomed love life; some portrayed them as innocent love bird sharing a coy kiss or two, others painted them in the moment of their deaths, and some focused on their buzzing afterlife in Inferno.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres is considered a Classicist and still elements of Romanticism, both stylistically and thematically, often pop up in his work; from the vibrant exoticism of his harem ladies and dark archaic touch of the Northern art in some of his portraits, to his portrayal of Medieval lovers caught in their forbidden earthly love. In his painting from 1819, he presented the two lovers enjoying each others company in a small elongated chamber the walls of which are covered in wood panels which makes the room resemble a box, perhaps suggesting the oppressive environment of their household. Francesca is painted in archaic robes and resembles a character from a painting of Northern Renaissance. Paolo, in his tights and a sword, is kissing her cheek as she turns her oval face away from him. As the old saying goes: “Two is a company, three is none”; the seeming peace of their love is interrupted by a figure in the background. It’s Giovanni, slowly drawing the curtain away only to see a shocking sight. The scene all together resembles a theatre scene and the narrative aspect is very strong, Ingres is leading us thought the story with little details and gestures. The very moment Giovanni is about to raise his sword, Francesca’s book is caught in its fall to the ground.

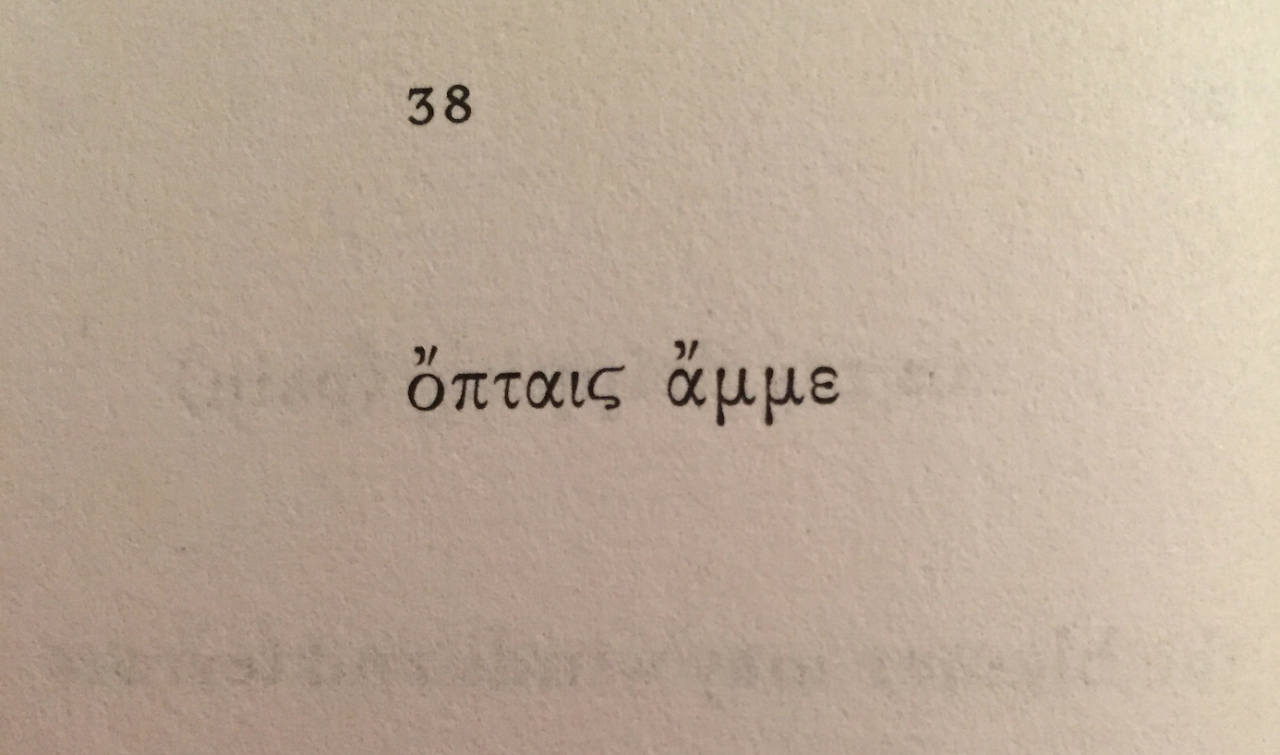

William Dyce, Francesca da Rimini, 1837

Francesca was born in 1255 in Ravenna, her father was the lord of Ravenna; an Italian town on the Adriatic coast with a strong Byzantine influence, and the last place to be the centre of Western Roman Empire in the fifth century. Around the age of twenty she married Giovanni Malatesta, the wealthy yet crippled lord of Rimini, sometimes also known as “Gianciotto” or “Giovanni the Lame”. Similarly to the story of Tristan and Isolde, Francesca wasn’t in love with Giovanni, it was just an arranged marriage after all, but her eyes soon took notice of Giovanni dashing younger brother Paolo. Gaze turned into a conversation, and words into kisses and caresses… Paolo was also married, and yet the two managed to keep their love a secret for ten years. William Dyce portrayed the couple as sitting on a balcony; Francesca is reading a book while Paolo is rushing to kiss her. Behind them is a serene verdant landscape, the moon shines in the right corner, and next to Francesca’s feet is an instrument, I am guessing, a lute which might add a sensuous touch to the scene. The scene is all together a bit too sentimental. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, hailing from Italy himself and an ardent admirer of Dante’s poetry and his life, envisaged the scene differently. In his watercolour, he portrays the couple as sitting in a chamber; pink roses are blooming, fresh air is coming in through the window, and, distracted from whatever they were reading, the couple share a passionate kiss. The book, half on his lap and half on hers, is about to fall down on the thorns of some more pink roses.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, 1867, watercolour

Death

The secret kisses turned out to be not so secret after all, for one day, around 1285, Giovanni caught them off guard, in Francesca’s bedroom. His blood fueled from rage and jealousy, and without much thinking Giovanni yielded the sword and deprived them both of life. Well, unfortunately, it wasn’t so dramatic in reality. What really happened was that Giovanni had heard some rumours about his wife cheating on him, and he rushed to her chamber. Francesca let him in because she was certain that Paolo had managed to escape through the window, but what she didn’t know was the he got stuck. Giovanni then tried to kill his brother, but Francesca tried to defend him, and was killed instead. Giovanni then proceeded to kill Paolo as well. Later they were buried in a single tomb; how devastatingly romantic is that!?

Alexandre Cabanel, The death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, 1870

Alexandre Cabanel was a French Academic painter and the way he envisaged the scene of Paolo and Francesca’s death is very theatrical. They are both dressed in splendid clothes, their pale faces are full of pathos, their gestures tell a story of their agony. Francesca is lying on something which looks more like a sarcophagus than a bed, and the ornamental marble floor further emphases the mood of coldness and death. Meanwhile, Giovanni is checking behind the curtain one more time to be sure they are indeed dead. Previati portrayed the scene of their death in a very dramatic way, using an elongated canvas and focusing on the figures themselves and not so much on the interior. Our eyes are focused on the bodies and the agony and pain of their sudden death. The painting is striking; there is still a sword in Paolo’s back, and his arm is limp, and Francesca’s hand is on her chest while her mouth are still slightly open as if she’s still catching her breath.

Gaetano Previati, Paolo e Francesca, ca. 1887

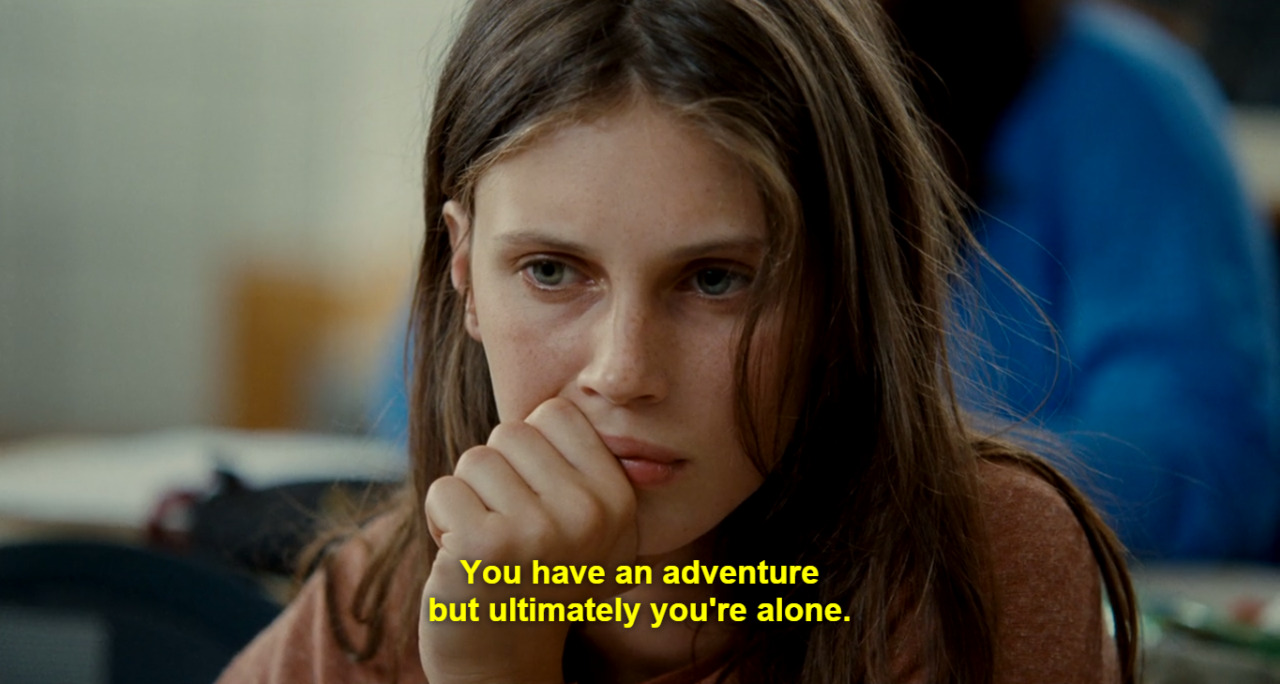

Wind of Passion

Death is no the end, as Nick Cave says in one of his songs. Almost a thousand years had passed from their deaths, but Paolo and Francesca are still embraced and carried away by the wind of passion. It is almost hard to imagine that before their eternity of damnation they were of mortal flesh just as we are now. Dante shows both disapproval of their life choices and a sympathy when he finally meets them in Inferno. I am thinking: wow, what a way to spend eternity! Being carried by the wind, safe in the arms of the one you love. Sounds like heaven, not hell.

George Frederic Watts, Paolo et Francesca, 1872-75

When Dante met Paolo and Francesca in Hell, this is what he said:

“And I began: “Thine agonies, Francesca,

Sad and compassionate to weeping make me.

But tell me, at the time of those sweet sighs,

By what and in what manner Love conceded,

That you should know your dubious desires?”

And Francesca responds:

And she to me: “There is no greater sorrow

Than to be mindful of the happy time

In misery, and that thy Teacher knows.

But, if to recognise the earliest root

Of love in us thou hast so great desire,

I will do even as he who weeps and speaks.

One day we reading were for our delight

Of Launcelot, how Love did him enthral.

Alone we were and without any fear.

Full many a time our eyes together drew

That reading, and drove the colour from our faces;

But one point only was it that o’ercame us.

When as we read of the much-longed-for smile

Being by such a noble lover kissed,

This one, who ne’er from me shall be divided,

Kissed me upon the mouth all palpitating.

William Blake, The Lovers’ Whirlwind, Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, 1824-27

Tags: Alexandre Cabanel, art, Canto V, Dante Alighieri, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Death, Death is not the end, Francesca da Rimini, Gaetano Previati, George Frederick Watts, Inferno, Ingres, Italy, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, kiss, love, love affair, Medieval era, Painting, Paolo and Francesca, passion, Romanticism, Rossetti, watercolour, whirlwind of passion, Wiliam Dyce, William Blake

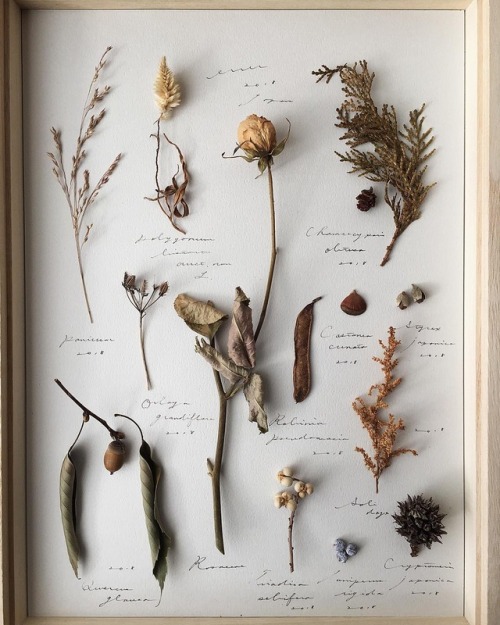

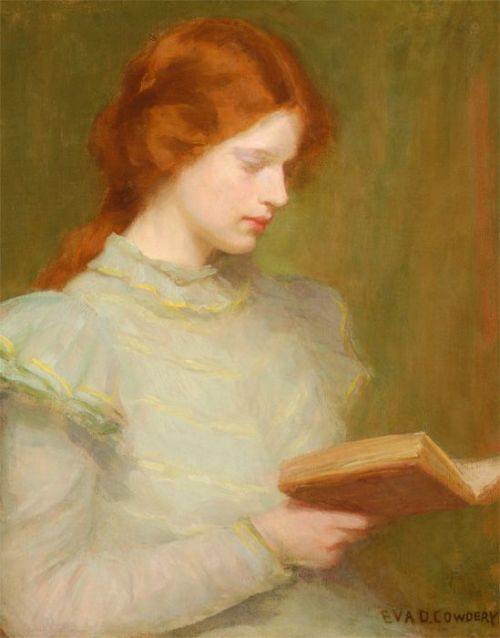

Photo by Nishe (Magdalena Lutek), found here.

Photo by Nishe (Magdalena Lutek), found here.