“M.C.G.[Monsieur Constantin Guys]loves mixing with the crowds, loves being incognito, and carries his originality to the point of modesty.”

(Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life)

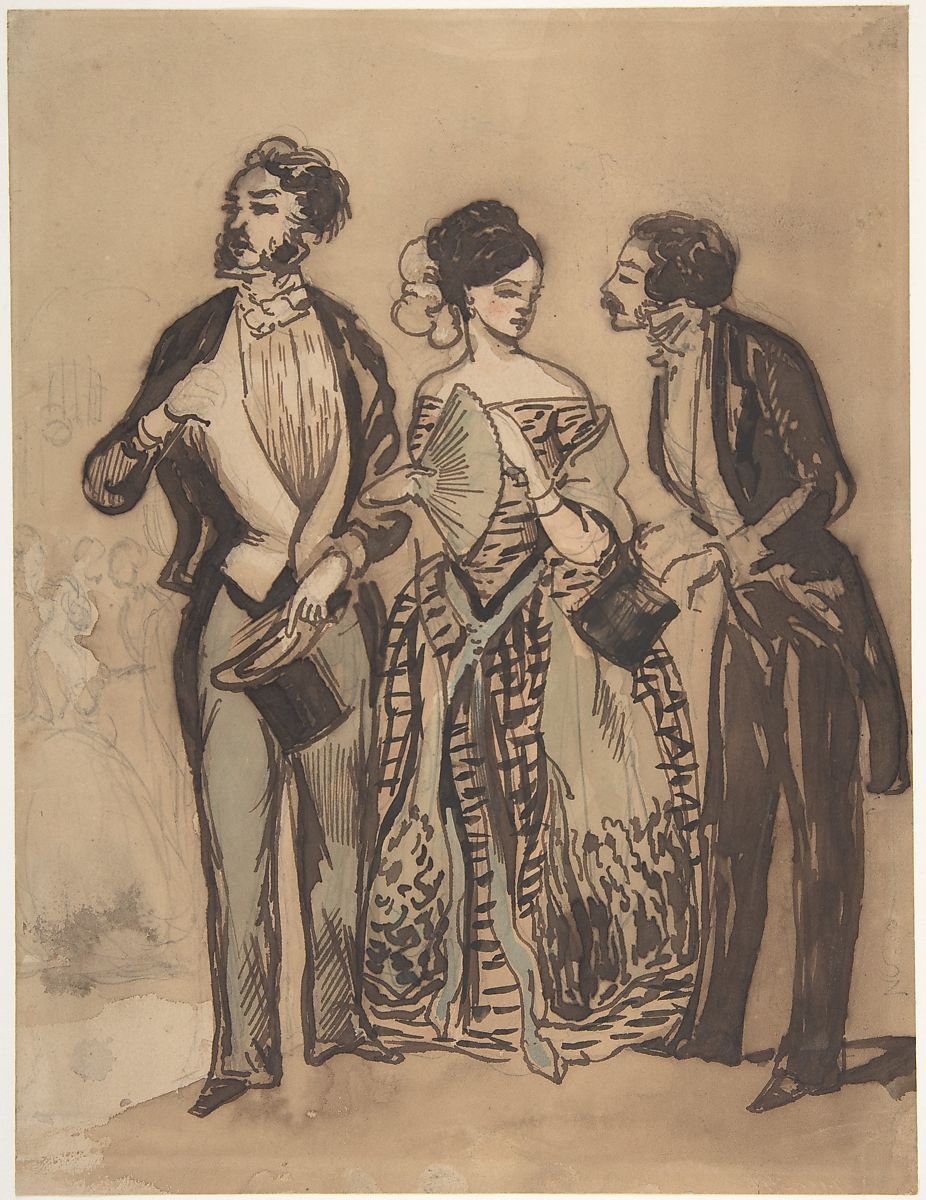

Constantin Guys, A Grisette, 1859, Pen and ink with ink and watercolor washes on wove paper

Constantin Guys, A Grisette, 1859, Pen and ink with ink and watercolor washes on wove paper

These watercolours and drawings by Constantin Guys have caught my attention these days. I just love how brilliantly they capture the vibrant and busy social life of the mid-nineteenth century rich and posh Parisians. Guys is almost like a precursor to a paparazzi, capturing every move, every laughter, every nuance of what is going on. These works were mostly made during the Second French Empire times; from 1852 to 1870, and lucky for us viewers, those decades were the decades of the sumptous and extravagant fashion for women, mostly because of the crinoline which made the skirts excessively wide thus making the women look like giant lotus flowers walking around. These sketchy and quick yet so vivid and detailed pen and ink drawings with watercolour washes give us a sneak peek into the era that is gone by. But Guys doesn’t just paint the wealthy ladies. His drawing of a grisette from 1859 can vauch for that. A grisette is a flirtatious coquettish working class woman. Guys stunningly captures the flounces of her dress and the way he painted the black fabric makes it appear like waves on the dark waters of Venice. His use of blue is equally thrilling in the drawing “Leaving the theatre”. Guys seems always to be walking on the tightrope between sketchiness and brimming with details.

I imagine these ladies and gentlemen are the characters from Gautier’s stories, from Chopin’s concerts, maybe one of these beauties is the fatal mistress of Mr Rochester from Charlotte Bronte’s novel Jane Eyre, stepping out of the carriage and giving a kiss to her other lover while Mr Rochester awaits her on the balcony, hidden by the roses, heartbroken and disappointed. I imagine these are the kind of ladies that Balzac wrote about in Father Goriot, the kind of ladies who know every little gossip and secret of Parisian budoirs and bedroom, they are the flies on every wall and no one is safe from their watchful eye. But little do they know that all along Monsieur Guys is gandering at them from afar, his eyes catching scenes like the camera, his hand drawing on its own. It is for a reason that the decadent poet Charles Baudelaire called him “the painter of modern life” in his essay of the same-name. In that essay he especially praises Guy’s endless curiosity about life and the world around him, the same curiosity that children have and which makes them ecstatic about everything. This curiosity, tied with perceptiveness, artistic skill and a flaneur lifestyle make Guys the brilliant painter that he was. Here are some interesting passages from Baudelaire’s essay:

“Today I want to talk to my readers about a singular man, whose originality is so powerful and clear-cut that it is self-sufficing, and does not bother to look for approval. None of his drawings is signed, if by signature we mean the few letters, which can be so easily forged, that compose a name, and that so many other artists grandly inscribe at the bottom of their most carefree sketches. But all his works are signed with his dazzling soul, and art-lovers who have seen and liked them will recognize them easily from the description I propose to give of them.

Constantin Guys, Leaving the Theatre, 1852, Pen and brown ink, brush and black, gray, red, blue, and yellow wash

M. C. G. [Monsieur Constantin Guys] loves mixing with the crowds, loves being incognito, and carries his originality to the point of modesty. (…) when he heard that I was proposing to make an assessment of his mind and talent, he begged me, in a most peremptory manner, to suppress his name, and to discuss his works only as though they were the works of some anonymous person. I will humbly obey this odd request. (…) M. G. is an old man. Jean-Jacques began writing, so they say, at the age of forty-two. Perhaps it was at about that age that M. G., obsessed by the world of images that filled his mind, plucked up courage to cast ink and colours on to a sheet of white paper. To be honest, he drew like a barbarian, like a child, angrily chiding his clumsy fingers and his disobedient tool. I have seen a large number of these early scribblings, and I admit that most of the people who know what they are talking about, or who claim to, could, without shame, have failed to discern the latent genius that dwelt in these obscure beginnings.

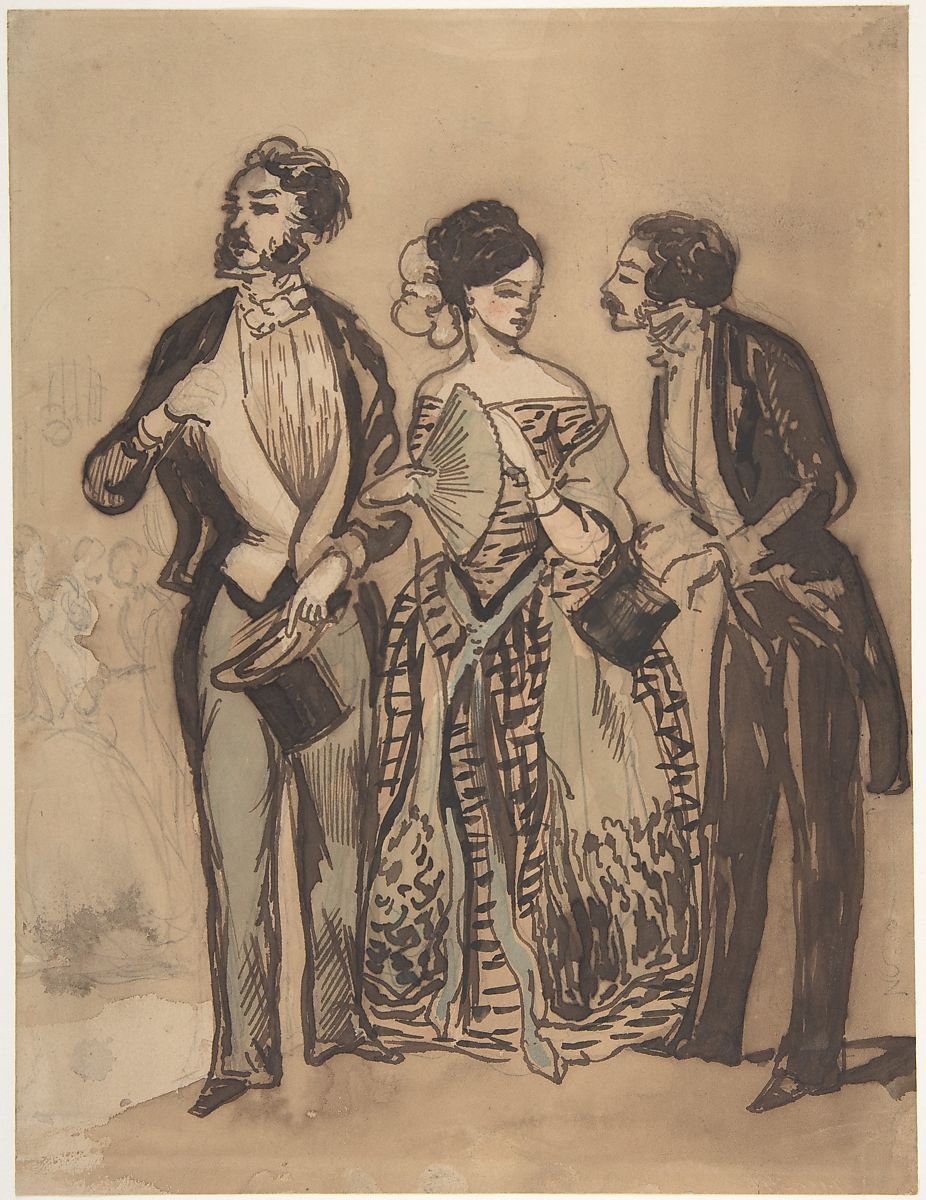

Constantin Guys, Two Gentlemen and a Lady, n.d., Pen and brown ink, brush and brown, green and blue wash, over graphite; touches of red chalk

Today, M. G., who has discovered unaided all the little tricks of the trade, and who has taught himself, without help or advice, has become a powerful master in his own way; of his early artlessness he has retained only what was needed to add an unexpected spice to his abundant gift. When he happens upon one of these efforts of his early manner, he tears it up or burns it, with a most amusing show of shame and indignation. In this context, pray interpret the word ‘artist’ in a very narrow sense, and the expression ‘man of the world’ in a very broad one. By ‘man of the world’, I mean a man of the whole world, a man who understands the world and the mysterious and legitimate reasons behind all its customs; by ‘artist’, I mean a specialist, a man tied to his palette like a serf to the soil. M. G. does not like being called an artist. Is he not justified to a small extent?

He takes an interest in everything the world over, he wants to know, understand, assess everything that happens on the surface of our spheroid. (…) With two or three exceptions, which it is unnecessary to name, the majority of artists are, let us face it, very skilled brutes, mere manual labourers, village pub-talkers with the minds of country bumpkins. (…) Thus to begin to understand M. G., the first thing to note is this: that curiosity may be considered the starting point of his genius.

Constantine Guys, Reception, 1847, Pen and brown ink with brush and watercolor, over graphite, on ivory laid paper

Do you remember a picture (for indeed it is a picture!) written by the most powerful pen of this age and entitled The Man of the Crowd? Sitting in a café, and looking through the shop window, a convalescent is enjoying the sight of the passing crowd, and identifying himself in thought with all the thoughts that are moving around him. He has only recently come back from the shades of death and breathes in with delight all the spores and odours of life; as he has been on the point of forgetting everything, he remembers and passionately wants to remember everything. In the end he rushes out into the crowd in search of a man unknown to him whose face, which he had caught sight of, had in a flash fascinated him. Curiosity had become a compelling, irresistible passion.

Now imagine an artist perpetually in the spiritual condition of the convalescent, and you will have the key to the character of M. G. But convalescence is like a return to childhood. The convalescent, like the child, enjoys to the highest degree the faculty of taking a lively interest in things, even the most trivial in appearance. Let us hark back, if we can, by a retrospective effort of our imaginations, to our youngest, our morning impressions, and we shall recognize that they were remarkably akin to the vividly coloured impressions that we received later on after a physical illness, provided that illness left our spiritual faculties pure and unimpaired. The child sees everything as a novelty; the child is always ‘drunk’. Nothing is more like what we call inspiration than the joy the child feels in drinking in shape and colour.

Constantin Guys, Meeting in the Park, 1860, Pen and brown ink, brush and gray, blue, and black wash

I will venture to go even further and declare that inspiration has some connection with congestion, that every sublime thought is accompanied by a more or less vigorous nervous impulse that reverberates in the cerebral cortex. (…) But genius is no more than childhood recaptured at will, childhood equipped now with man’s physical means to express itself, and with the analytical mind that enables it to bring order into the sum of experience, involuntarily amassed. To this deep and joyful curiosity must be attributed that stare, animal-like in its ecstasy, which all children have when confronted with something new, whatever it may be, face or landscape, light, gilding, colours, watered silk, enchantment of beauty, enhanced by the arts of dress.”

Tags: 1840s, 1850s, art, Baudelaire, Constantin Guys, creativity, Crinoline, curiosity, drawing, Everyday life, fashion, grisette, modernity, painter of modern life, Paris, Second French Empire, watercolour, Women

Kay Nielsen, Illustration for The Story of a Mother, c. 1910

Kay Nielsen, Illustration for The Story of a Mother, c. 1910

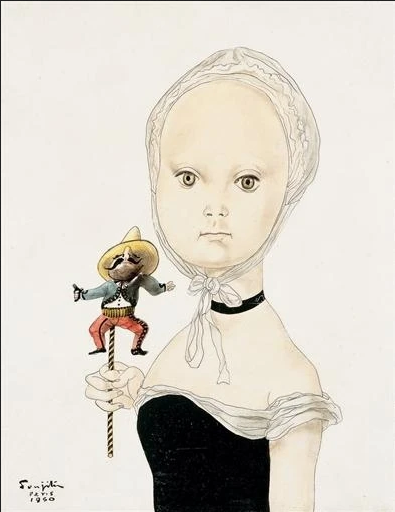

Foujita, Little Girl with a Mexican Doll (Fillette à la poupée mexicaine), 1950

Foujita, Little Girl with a Mexican Doll (Fillette à la poupée mexicaine), 1950