“Love led us straight to sudden death together.”

(Dante, Inferno, Canto V)

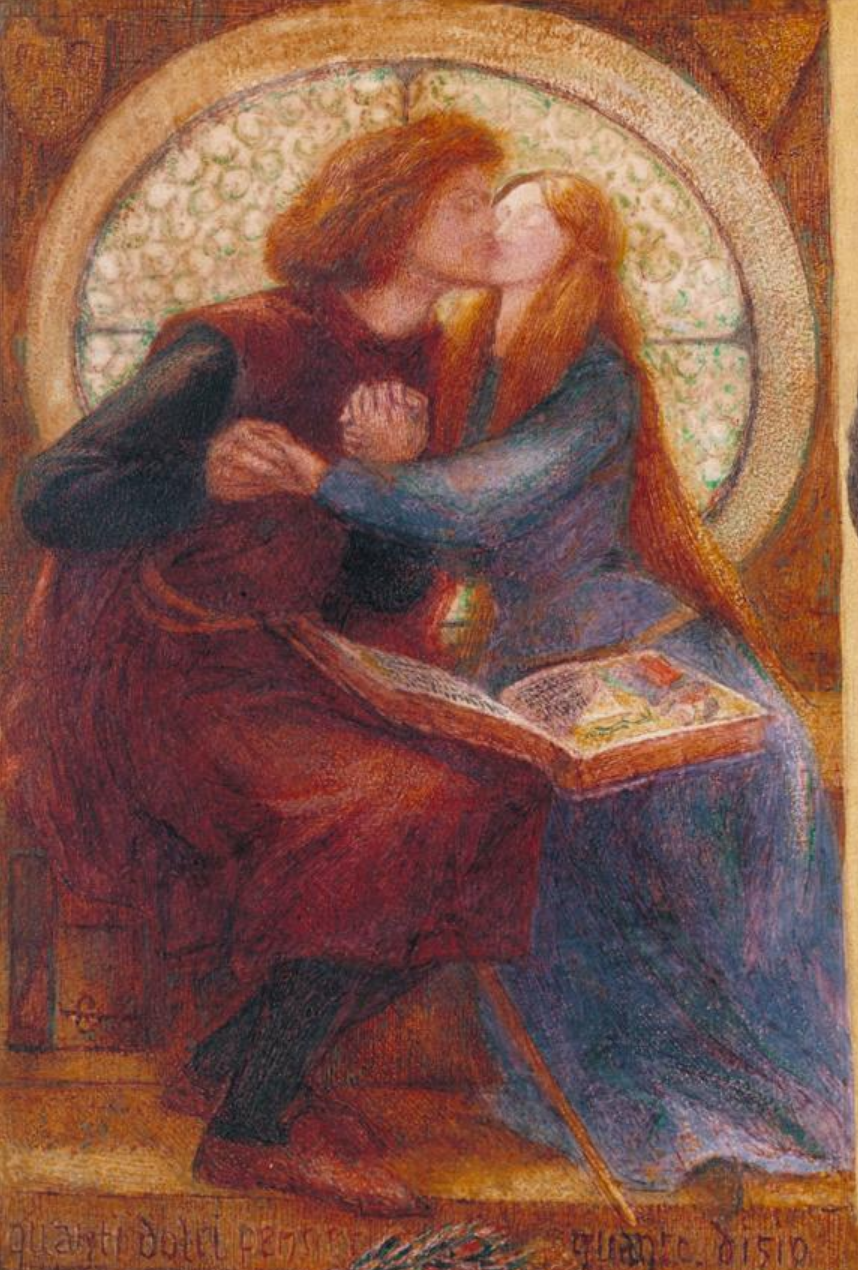

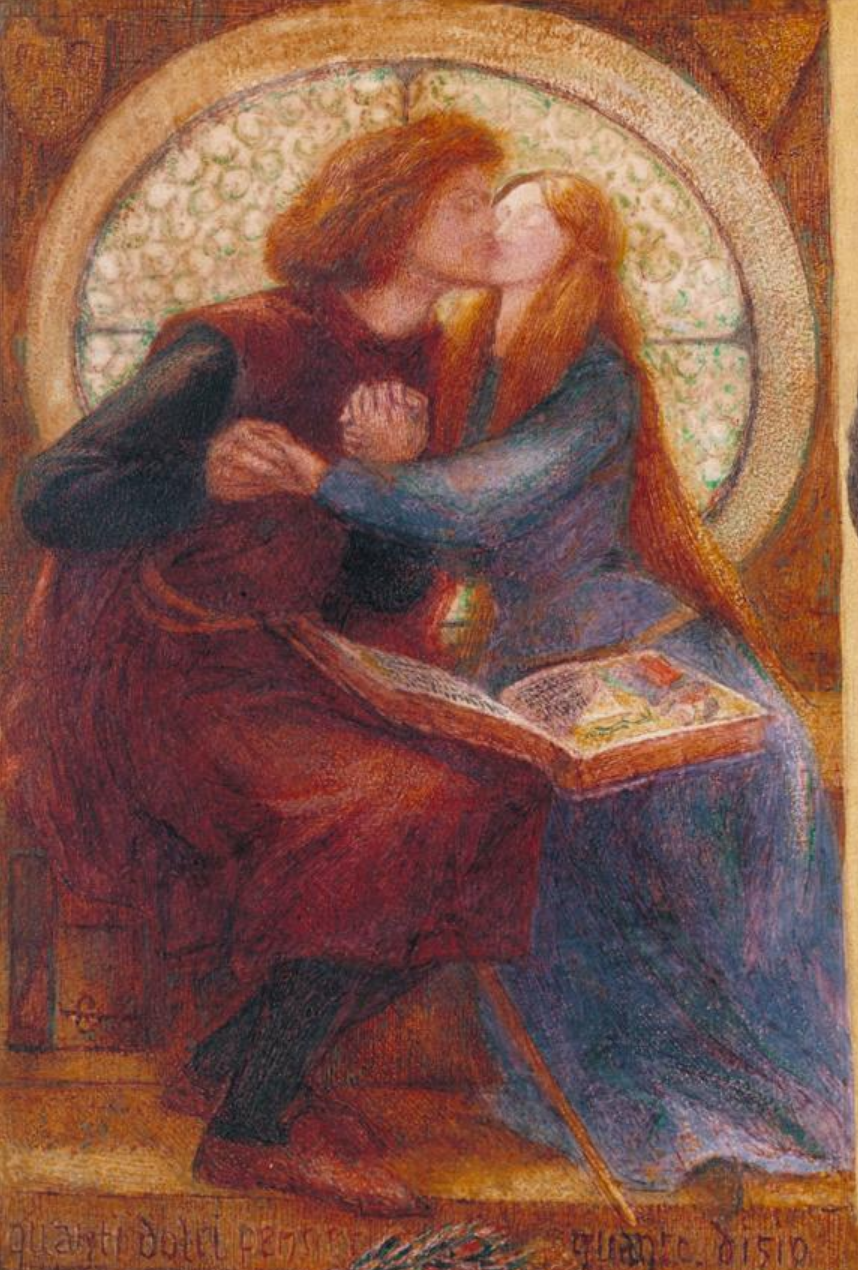

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, 1855, watercolour

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, 1855, watercolour

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, an English poet, painter, illustrator, translator and most importantly the founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, was born on this day in 1828 in London so let us use the opportunity and remember the fascinating and charismatic artist on his birthday. Rossetti had artistic aspirations from an early age and his siblings shared those aspirations as well. His maternal uncle was John William Polidori; the friend of Lord Byron and the author of the short story “The Vampyre” (1819). He died seven years before Rossetti was born, but it shows what kind of family ancestry Rossetti had and why it was perfectly natural for him to aspire to become a poet and an artist. Half-Italian and half-mad, Rossetti idealised and glorified the Italian past, especially the Medieval era and the writings of Dante Alighieri; a hero whom he worshipped. In 1848 he founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood along with William Holman Hunt whose painting “The Eve of St. Agnes” Rossetti had seen on an exhibition and loved, and the young prodigy John Everett Millais. Their aim was to paint again like the old masters did; with honesty and convinction, using vibrant colours and abundance of details, and most of all; to paint from the heart.

In 1850, two very important things happened in Rossetti’s life; he met Elizabeth Siddal; a moody and melancholy redhaired damsel who was to become the main object of his adoration in decade to come, his pupil, his lover and muse; and, he focused on painting watercolours. In the 1850s Rossetti’s head wasn’t all in the clouds of love, no half of it was in the rose-tinted clouds of the past, his main artistic inspirations being the Arthurian legends and Dante.

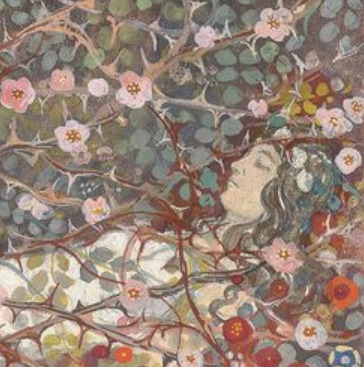

His watercolour “Paolo and Francesca da Rimini” from 1855 is a synthesis of these two inspirations; his love Lizzy Siddal and Dante. The watercolour is a tryptich (read from left to right) in intense, rich colours portraying the tale of doomed lovers Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini who was the wife of his brother. Paolo and Francesca were real-life historical figures, but Rossetti’s inspirations stems from Dante’s Inferno, specifically from the Canto V where Dante and Virgil, portraid in the central panel of the tryptich, enter the part of Hell where the souls of passionate and sinful lovers remain for eternity. The first tryptich shows Paolo and Francesca in a kiss. A secret, guilty, and forbidden kiss and yet Rossetti’s scene only shows a tender and passionate moment between lovers, their hands clasped together, Paolo pulling her closer. Francesca’s long red hair and face resemble the hair and face of Elizabeth Siddal, and the figure of Paolo was based on Rossetti himself. It is as if he knew that his love would be as doomed, though in a different way, just like that of Paolo and Francesca.

The interior is simple and allows the focus to be on the couple and their secret kiss. A plucked rose on the floor, an opened book with glistening illuminations is on Francesca’s lap shows the activity that bonded the pair and made the kiss inevitable, from Dante’s Inferno, Canto V:

Dante asks Francesca:

“But tell me, in that time of your sweet sighing

how, and by what signs, did love allow you

to recognize your dubious desires?”

And she responds:

And she to me: “There is no greater pain

than to remember, in our present grief,

past happiness (as well your teacher knows)!

But if your great desire is to learn

the very root of such a love as ours,

I shall tell you, but in words of flowing tears.

One day we read, to pass the time away,

of Lancelot, how he had fa llen in love;

we were alone, innocent of suspicion.

Time and again our eyes were brought together

by the book we read; our fa ces flushed and paled.

To the moment of one line alone we yielded:

it was when we read about those longed-for lips

now being kissed by such a famous lover,

that this one (who shall never leave my side)

then kissed my mouth, and trembled as he did.“

When I gaze at this left panel of the tryptich, a lyric from Bruce Springsteen’s song “The River” comes more and more to my mind, I wonder does the memory of the kiss come back to haunt Paolo and Francesca in hell:

“Pull her close just to feel each breath she’d take

Now those memories come back to haunt me

They haunt me like a curse

Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true

Or is it something worse

That sends me down to the river

Though I know the river is dry…”

“When finally I spoke, I sighed, “Alas,

what sweet thoughts, and oh, how much desiring

brought these two down into this agony.”

(Dante, Inferno, Canto V)

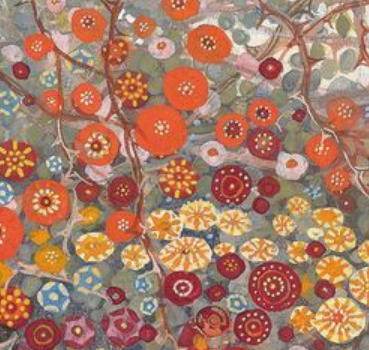

The central part of the tryptich, as I’ve said, shows Dante and Virgil. The third or the right wing of the tryptich shows the afterlife of the doomed lovers in Hell. Just like the sould of other unfortunate and lustful lovers, Paolo and Francesca are shown being carried by the wind of passion that swept them away in their living life on earth too, in each other’s arms for eternity. Are they being mercilessly carried by the wind, or have they overpowerd it and are riding it blissfully? All around them flames of hell dance like shooting stars. Quite romantic actually, I don’t see where the punishment part comes myself. Still, there is a message and the tale of doomed lovers in hell shows how a single moment and a single step is enough to commit a sin; the kiss was the act of weakness and passion. That single moment of weakness endangered forever their possibility of eternal glory.

Unlike other artists before him who have portrayed the story of Paolo and Francesca, Rossetti convinently avoids portraying the bloody and gruesome moment when the lovers are caught by Paolo’s brother Gianciotto who is also Francesca’s husband and murders them both. I really like that Rossetti painted a tryptich whose theme isn’t religious but profane, though some, like John Keats – another Rossetti’s hero – argue that love is sacred. After all, a tryptich is just an artwork divided into three panels, telling a story, kind of like a modern comic book so there is really no need for it to be restricted to religious topics. We can view this watercolour then as a Tryptich of the Religion of Love. And to end, here is a quote from Keats’ letter to Fanny Brawne, from 13 October 1819:

“I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion – I have shudder’d at it – I shudder no more – I could be martyr’d for my Religion – Love is my religion – I could die for that – I could die for you.”

Tags: 1855., afterlife, art, Birthday, Dante, Death, Elizabeth Siddal, flames of hell, hell, Inferno, Italian, Italy, John Keats, Keats, love, love is my religion, lovers, Muse, Painting, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, passion, Pre-Raphaelites, red hair, romance, Romantic, Rossetti, Victorian era, watercolour

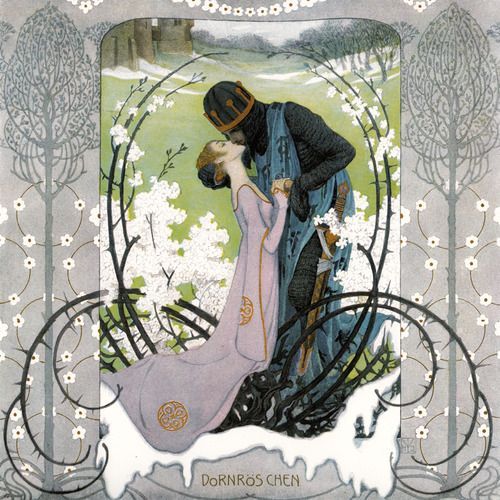

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, St George and Princess Sabra, 1862, watercolour

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, St George and Princess Sabra, 1862, watercolour