I love Brigitte Bardot; her presence on the screen is simply delightful, her face is more beautiful than any painting to me, her pouting, her hair, her gaze, the way she walks… enchanting! She doesn’t seem to be acting at all, as Roger Vadim had said, she is just there, being herself. I love her in the early films of her career; “And God Created Woman” (1956), “Love is My Profession” (or “A Case of Adversity, 1957), and La Vérité (1960) in which the handsome Sami Frey plays the role of her lover. The other day I read Simone de Beauvoir’s essay called “Brigitte Bardot and the Lolita Syndrome”, originally published in 1959 and I thought I’d share some interesting passages about Brigitte Bardot as the nymphet, a woman-child, the untamed waif. Everything bellow is from de Beauvoir’s essay, not my words:

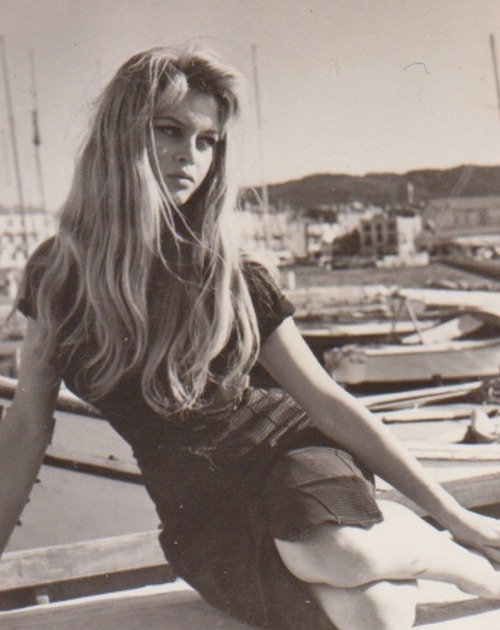

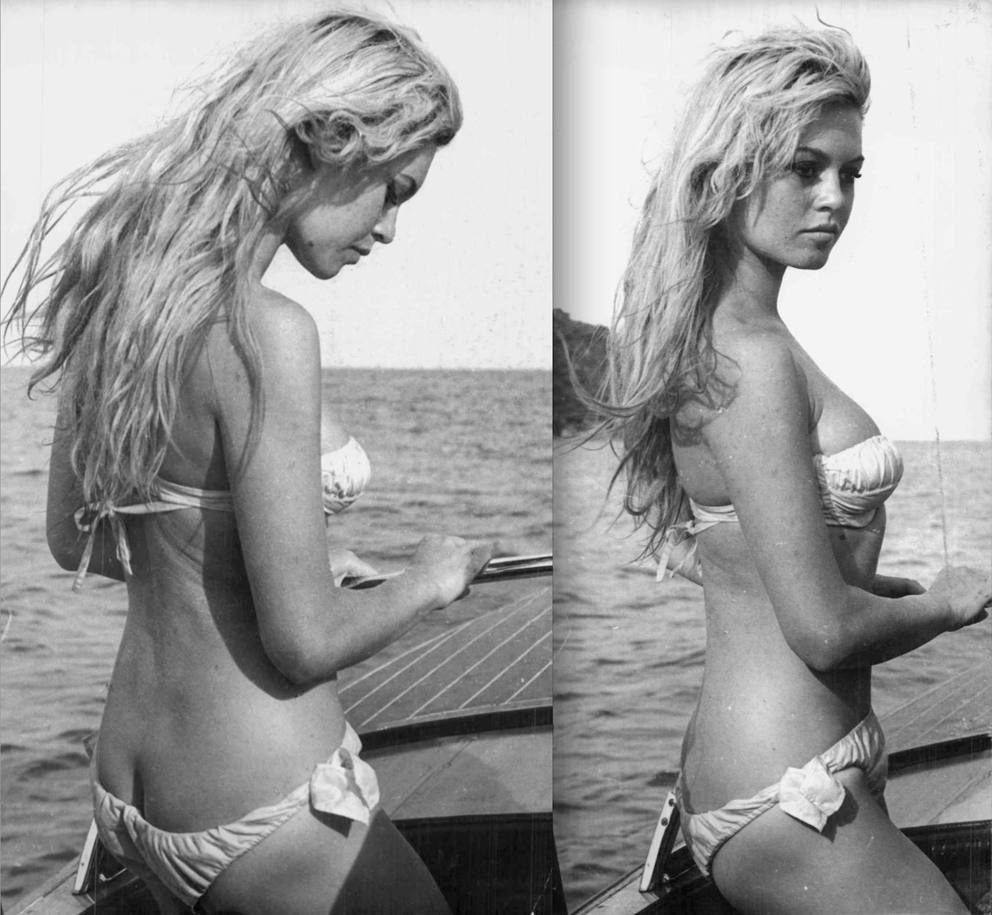

Brigitte Bardot in “Une parisienne”, 1957

Brigitte Bardot in “Une parisienne”, 1957

“Nabokov’s “Lolita” which deals with the relations between a forty-year-old male and a ‘nymphet’ of twelve, was at the top of the best-seller list in England and America for months. The adult woman now inhabits the same world as the man, but the child-woman moves in a universe which he cannot enter. The age difference re-established between them the distance that seems necessary for desire. At least that is what those who have created a new Eve by merging the ‘green fruit’ and ‘femme fatale’ types have pinned their hopes on.

(….) Brigitte Bardot is the most perfect specimen of these ambiguous nymphs. Seen from behind, her slender, muscular, dancer’s body is almost androgynous. Femininity triumphs in her delightful bosom. The long voluptuous tresses of Mélisande flow down to her shoulders, but her hair-do is that of a negligent waif. The line of her lips forms a childish pout, and at the same time those lips are very kissable. She goes about barefooted, she turns up her nose at elegant clothes, jewels, girdles, perfumes, make-up, at all artifice. Yet her walk is lascivious and a saint would sell his soul to the devil merely to watch her dance. It has often been said that her face has only one expression. It is true that the outer world is hardly reflected in it at all and that it does not reveal great inner disturbances. But that air of indifference becomes her. BB has not been marked by experience. Even if she has lived – as in “Love is my profession” – the lessons that life has given her are too confused for her too have learned anything from them. She is without memory, without a past, and, thanks to this ignorance, she retains the perfect innocence that is attributed to a mythical childhood.

(…) Vadim presented her as a ‘a phenomenon of nature.’ ‘She doesn’t act’, he said. ‘She exists.’ (…) She was moody and capricious. (…) She was described as a creature of instinct, as yielding blindly to her impulses. She would suddenly take a dislike to the decoration of her room and then and there would pull down the hangings and start repainting the furniture. She is temperamental, changeable and unpredictable, and though she retains the limpidity of childhood, she has also preserved its mystery. A strange little creature, all in all; and this image does not depart from the traditional myth of femininity. She appears as a force of nature, dangerous so long as she remains untamed, but it is up to the male to domesticate her. She is kind, she is good-hearted. In all her films she loves animals. If she ever makes anyone suffer, it is never deliberately.

Her flightiness and slips of behaviour are excusable because she is so young and because of circumstances. Juliette had an unhappy childhood; Yvette, in ‘Love is my profession’, is a victim of society. If they ever go astray, it is because no one has ever shown them the right path, but a man, a real man, can lead them back to it. Juliette’s young husband decides to act like a male, gives her a good sharp slap, and Juliette is all at once transformed into a happy, contrite and submissive wife. Yvette joyfull accepts her lover’s demand that she be faithful and his imposing upon her a life of virtual seclusion. With a bit of luck, this experienced, middle-aged man would have brought her redemption. BB is a lost, pathetic child who needs a guide and protector. This cliché has proved its worth. It flatters masculine vanity.

(…) BB is neither perverse nor rebellious nor immoral, and that is why morality does not have a chance with her. Good and evil are part of conventions to which she would not even think of bowing.”