“The eyes of the Mexicans are full of burning life. They squat like Orientals next to wide, flat baskets full of fruit and vegetables arranged with a fine sense of design, of decorative art and harmonies. Strings of chili hang from the rafters. The scent of saffron, and rhythms of Chagall-colored laundry hanging like banners from windows, and in gardens.”

Diego Rivera, The Flower Vendor (Girl with Lillies), 1941

Diego Rivera, The Flower Vendor (Girl with Lillies), 1941

I was reading bits and bops of Anais Nin’s 1947-1955 diary and I stumbled upon this passage where she vividly describes the vibrancy of people and life in Mexico; the colours, the festival mood, the markets with the fruit and flower vendors… It all made me think of the paintings by Mexican artists such as Diego Rivera, Olga Costa and Alfredo Ramos Martinez which seem like a perfect visual companion to Anais Nin’s written record. Now, here is that passage from her diary:

“Everywhere guitars. As soon as one guitar moves away, the sound of another takes its place, to continue this net of music that maintains one in flight from sadness, suspended in a realm of festivities.

Festivities. Fiestas. Holidays. Bursts of color and joy. Collective celebrations. Rituals. Indian feasts and Catholic feasts. Any cause will do. Even the very poor know how to dress up a town with colored paper cut outs which dance in the wind. What was happened to joy in America? The Americans in the hotel spend all their time drinking by the pool. The men go hunting flamingos, which they shoot for the pleasure of it. Or they fish for inedible mantarayas and weigh their spoils to win prizes.

The eyes of the Mexicans are full of burning life. They squat like Orientals next to wide, flat baskets full of fruit and vegetables arranged with a fine sense of design, of decorative art and harmonies. Strings of chili hang from the rafters. The scent of saffron, and rhythms of Chagall-colored laundry hanging like banners from windows, and in gardens. Warmth falls from the sky like the fleeciest blanket. Even the night comes without a change of temperature or alteration in the softness of the air. You can trust the night.

There is a rhythm in the way the women lift the water jugs onto theirheads and walk balancing them. There is a rhythm in the way they carry their babies wrapped in their shawls, and their baskets filled with fruit. There is a rhythm in the way the fishermen pull in their nets in the evening, and the way the shepherds walk after their lambs and cows.”

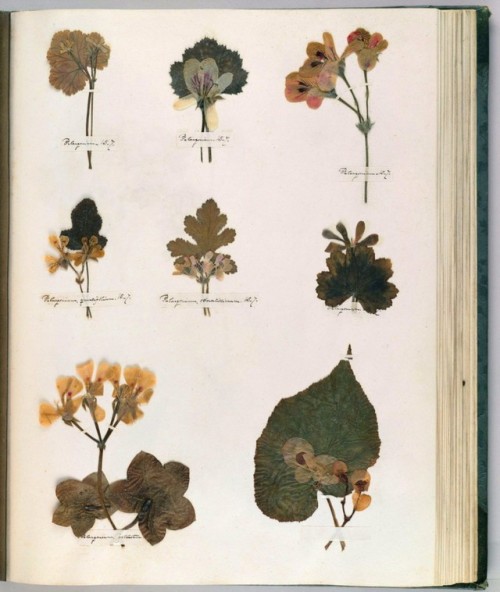

Olga Costa, Fruit-Seller (La vendedora de frutas), 1951

Olga Costa, Fruit-Seller (La vendedora de frutas), 1951

The first painting in this post, Diego Rivera’s “The Flower Vendor” also known as “Girl with Lillies” is the first thing that came to my mind after reading that passage by Anais Nin. The painting is showing an indigenous girl with braided hair who is kneeling down, with her back turned away from us, and holding a massive, exaggeratedly large bundle of lilies. The painting is very visually catching and interesting. The lilies are stylised and so overpowering in their size which gives the painting a flair of the magic realism as found in the novels of Gabriel García Márquez, but the girl’s bare feet and her kneeling pose speak more of realism and less of magic. She is clearly a poor, working class girl who is only selling lilies but will never get to enjoy their delicate beauty and dazzling scent; such things are for the upper classes whereas she is small and anonymous, as hinted by her pose; we don’t see her face and we don’t know who she really is.

Olga Costa’s painting “Fruit-Seller” painted only a decade after Rivera’s painting offers a merrier, simpler depiction of a woman working as a fruit seller at the market. Olga Costa was a painter born in Germany to parents originally from Czarist Russia. The family had emigrated to Mexico in 1925 when Costa was twelve years old. Despite not being a native Mexican, her paintings speak of her passion for Mexican culture and people. She painted vibrant paintings with motifs that ooze the spirit of Mexico, such as indigeous barefoot girls, palm trees and lush fruits, women dressed in traditional attire, in a similar way that Frida Kahlo’s paintings do. Interestingly, her interest in painting was sparked after seeing the vibrantly coloured murals painted by Diego Rivera in the at the Anfiteatro Simón Bolivar. The painting “Fruit-Seller” shows a diverse array of all sorts of delicious and brightly coloured tropical fruits. Bananas, coconut, dragon fruit, pineapple… Truly, it’s a painted paradise! And still, the woman selling the fruit seems to be in the shadow, less important that the fruit she is selling, a small, sombre figure in the background offering us a half of a dragon fruit.

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Flower Vendor, c 1934

A third painter for this post is yet another Mexican painter: Alfredo Ramos Martínez’, whose 1934 painting “Flower Vendor” is reminiscent of Diego Rivera’s portrayal of the flower-vendors. Another dark skinned peasant girl with a heavy basket of fragrant, colourful flowers to sell. Her face is serious and silent. Both artists painted their flower vendors in a somewhat stylised, flattened manner, they strikes me as solid, sturdy and earthy, as if they grew from the soil and are still attached to it, just as the flowers they are selling are. The indigenous woman in Diego Rivera’s “Flower-Vendor” from 1926, shown bellow, strikes me as particularly melancholy and this sadness mixed with a wistful resignation stands in such contrast to the vibrancy of the flowers, but flowers, like life, come in all shades; they bloom and they wither.

A sense of rhythm, “bursts of color and joy”, “the eyes of the Mexicans are full of burning life”, “they squat like Orientals next to wide, flat baskets full of fruit and vegetables arranged with a fine sense of design”; I seek and I find all these things that Anain Nin has so vividly described in these paintings. Rivera’s 1935 painting shown bellow, “Tehuanas in the Market”, has that rhythm and liveliness that Nin writes of. The peasant women at the market are all wearing clothes in different colours which instantly creates a visual excitement. There is a dynamic of their work and conversation; some are arranging the bright yellow bananas in the baskets, and the others are chatting in groups, some more freely and some more secretively.

Diego Rivera, Tehuanas in the Market, 1935

Diego Rivera, Flower Vendor, 1926

Diego Rivera, Coconut Seller (Vendedora de Cocos), Watercolour on rice paper, 1935

“They squat like Orientals next to wide, flat baskets full of fruit and vegetables arranged with a fine sense of design…”