“I was prepared to love the whole world, but no one understood me, and I learned to hate.”

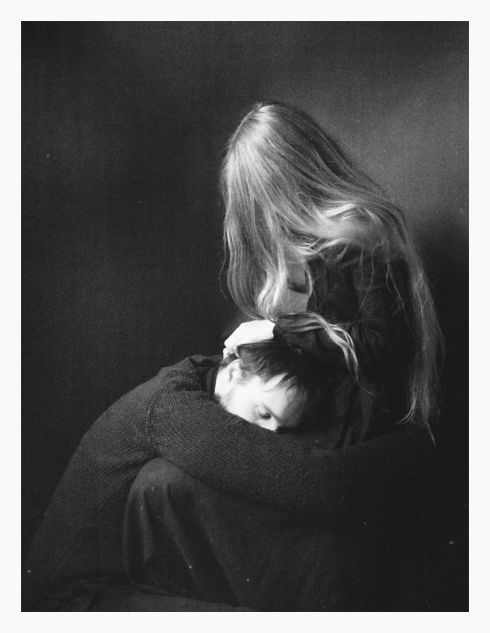

Christina Robertson, Grand-Duchesses Olga and Alexandra, Daughters of Nicholas I, 1840

Christina Robertson, Grand-Duchesses Olga and Alexandra, Daughters of Nicholas I, 1840

I first read Mikhail Lermontov’s fascinating novel “A Hero of Our Time” a few years ago and absolutely loved it and had so much fun reading it, especially the part called “Princess Mary”. The main character, a young man called Pechorin is very witty and his comments and remarks about the world, love, people around him are very amusing, and I can agree with him to some extent. I was literally laughing whilst reading it, some dialogues are just hysterical.

Lermontov wrote the novel in 1839 and it was published in 1840. A year later, Lermontov was dead. At the age of twenty-seven. How romantical!? To die in a duel at that age. The novel is divided into five parts, not in chronological order, and the part I love the most, called “Princess Mary”, is from Pechorin’s diary and it starts with his arrival to Pyatigorsk one beautiful day early in May. It starts with a lyrical description of nature in Caucasus and its effect on Pechorin’s state of mind and soul: “YESTERDAY I arrived at Pyatigorsk. I have engaged lodgings at the extreme end of the town, the highest part, at the foot of Mount Mashuk: during a storm the clouds will descend on to the roof of my dwelling. This morning at five o’clock, when I opened my window, the room was filled with the fragrance of the flowers growing in the modest little front-garden. Branches of bloom-laden bird-cherry trees peep in at my window, and now and again the breeze bestrews my writing-table with their white petals. The view which meets my gaze on three sides is wonderful (….) A feeling akin to rapture is diffused through all my veins. The air is pure and fresh, like the kiss of a child; the sun is bright, the sky is blue—what more could one possibly wish for? What need, in such a place as this, of passions, desires, regrets?”

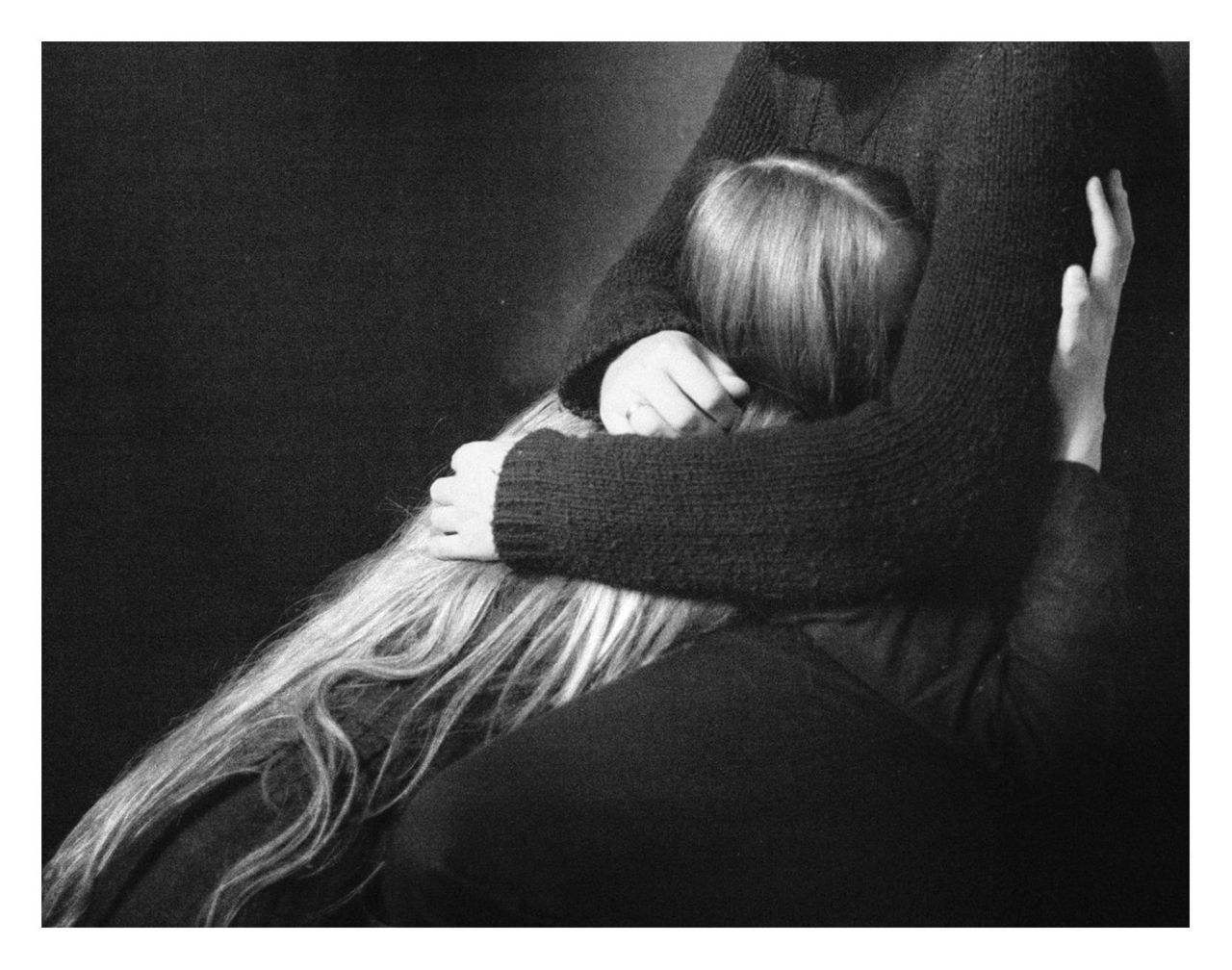

Grigory Gagarin, Ball, 1832

But very quickly Pechorin goes into society and the reader is introduced to other characters of whom Pechorin writes candidly; a fake sentimental cavalier Grushnitski, young, handsome and shallow emotions. This is how Pechorin describes him: “he has no knowledge of men and of their foibles, because all his life he has been interested in nobody but himself. His aim is to make himself the hero of a novel. He has so often endeavoured to convince others that he is a being created not for this world and doomed to certain mysterious sufferings, that he has almost convinced himself that such he is in reality. Hence the pride with which he wears his thick soldier’s cloak. I have seen through him, and he dislikes me for that reason, although to outward appearance we are on the friendliest of terms.” Grushnitski is therefore the opposite of Pechorin; the feelings of the former are shallow, while the latter hides the depth of his emotions and keeps them to himself. There is a clear similarity between Pushkin’s characters of Eugene Onegin who is a superflous man and Pechorin who is one also, and their counterparts: Pushkin’s character Vladimir Lensky is a naive romantic and is similar to Grushnitski.

Karl Bryullov, Horsewoman, 1832

A superflous man is a Russian version of a Byronic hero; Lermontov even mentions Lord Byron in his poetry and throughout the novel. Just like Byronic Hero, a superflous man is full of contradictions; he feels superior to his surroundings, yet he does nothing to put his talents and intelligence to good use, he is profound and has deep emotions but the society’s shallowness and superficiality has forced him to hide these deeper feelings because the world wouldn’t understand them. Prone to self-destruction, plagued by boredom, and possessing a sense that life in its core has no real meaning; all these things drive superflous men such as Eugene Onegin and Pechorin to travel aimlessly or indulge in flirtations that mean nothing to them. As long as the afternoon is pleasantly spent, true intentions of the heart don’t matter.

Duels, flirtations, gossips; this novel has these things in abundance and Pechorin simultaneously sees the emptiness of such a life, but nonetheless indulges in it because his cynical worldviews prevent him from believing in sincerity and love.

Ah, love, yes! What would a Romantic novel be without it. Pechorin gives women little reason to love him, and yet they do, but he gives a clear cynical justification for that: “Women love only the men they don’t know.” That is certainly true for these kind of novels; it’s the mystery of a man which is alluring to sweet, naive maidens because they then attribute all sorts of noble qualities to noblemen they’ve only seen from afar, and spoken maybe a few sentences with. Pechorin is led by the same selfish desire as Eugene Onegin was when he gave poor Tatyana false hopes and that is because to Pechorin nothing has meaning, he cherishes nothing, so how could he apprehend that things do matter to other people:

“I often ask myself why I am so obstinately endeavouring to win the love of a young girl whom I do not wish to deceive, and whom I will never marry. Why this woman-like coquetry? Vera loves me more than Princess Mary ever will. (…) There is, in sooth, a boundless enjoyment in the possession of a young, scarce-budded soul! It is like a floweret which exhales its best perfume at the kiss of the first ray of the sun. You should pluck the flower at that moment, and, breathing its fragrance to the full, cast it upon the road: perchance someone will pick it up! I feel within me that insatiate hunger which devours everything it meets upon the way….”

Princess Mary Ligovski doesn’t have a soul as deep and pure as Pushkin’s Tatyana, for after all, she is a haughty and well-educated young lady from Moscow who read Lord Byron’s work in English and knows algebra. Such a girl is not to messed with. It’s interesting to note that Pechorin started flirting with her only after Grushnitski admitted to him his secret affections for her. A superfluous man isn’t satisfied until he ruins and taints someone else’s prospects for happiness. And is he truly satisfied then? No, sadly, he is never satisfied, for to him life is but a pointless string of events, each more dull and less meaningful than the previous one, until sweet death comes. In one discussion in French with Grushnitski, Pechorin says “My friend, I despise women to avoid loving them because otherwise, life would become too ridiculous a melodrama.”

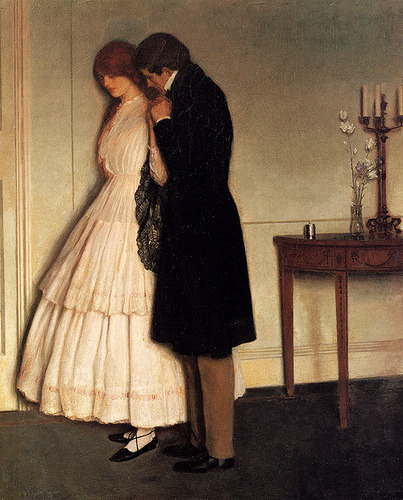

Karl Bryullov, The Shishmareva Sisters, 1839

In contrast to Princess Mary’s blind, youthful infatuation with Pechorin, it is another woman, Vera, a faithful beauty from Pechorin’s past who absolutely adores him. Mary fell for Pechorin because he is “tall, dark and handsome”, mysterious, alluring – and he doesn’t seem to be captivated by her which serves only as a motivation for her to win him over. He is the romantic hero that she has only read of, in dreary winter afternoons in Moscow. But Vera loves him deeply, even though their paths in life went differently, and even though she is married…. for the second time and not to him. Though she might be someone else’s wife on paper, her heart belongs to Pechorin only. She tells him, blushing, as they sit together in nature: “You know that I am your slave: I have never been able to resist you… and I shall be punished for it, you will cease to love me! At least, I want to preserve my reputation… not for myself—that you know very well!… Oh! I beseech you: do not torture me, as before, with idle doubts and feigned coldness! It may be that I shall die soon; I feel that I am growing weaker from day to day… And, yet, I cannot think of the future life, I think only of you… You men do not understand the delights of a glance, of a pressure of the hand… but as for me, I swear to you that, when I listen to your voice, I feel such a deep, strange bliss that the most passionate kisses could not take its place.”

And Pechorin later praises Vera’s depth of character: “Vera did not make me swear fidelity, or ask whether I had loved others since we had parted… She trusted in me anew with all her former unconcern, and I will not deceive her: she is the only woman in the world whom it would never be within my power to deceive. I know that we shall soon have to part again, and perchance for ever. We will both go by different ways to the grave, but her memory will remain inviolable within my soul. I have always repeated this to her, and she believes me, although she says she does not.”

Naive, silly goose, that is what Mary Ligovska is, to think that this dark and mysterious man will give up his cynicism and freedom to marry her. Pechorin makes his views on marriage quite clear: “…over me the word “marry” has a kind of magical power. However passionately I love a woman, if she only gives me to feel that I have to marry her—then farewell, love! My heart is turned to stone, and nothing will warm it anew. I am prepared for any other sacrifice but that; my life twenty times over, nay, my honour I would stake on the fortune of a card… but my freedom I will never sell. Why do I prize it so highly? What is there in it to me? For what am I preparing myself? What do I hope for from the future?… In truth, absolutely nothing.”

Natalia Pushkina, Portrait by Alexander Brullov, 1831

Here is a conversation between Pechorin and Vera which amused me so:

She gazed into my face with her deep, calm eyes. Mistrust and something in the nature of reproach were expressed in her glance.

“We have not seen each other for a long time,” I said.

“A long time, and we have both changed in many ways.”

“Consequently you love me no longer?”…

“I am married!”… she said.

“Again? A few years ago, however, that reason also existed, but, nevertheless”…

She plucked her hand away from mine and her cheeks flamed.

“Perhaps you love your second husband?”…

She made no answer and turned her head away.

“Or is he very jealous?”

She remained silent.

Mikhail Lermontov, Self-portrait, 1837

And to end, here is my favourite passage from the novel which I find totally relatable:

“Everyone saw in my face evil traits that I didn’t possess. But they assumed I did, and so they developed. I was modest, and was accused of being deceitful: I became secretive. I had a strong sense of good and evil; instead of kindness I received nothing but insults, so I grew resentful. I was gloomy, other children were merry and talkative. I felt myself superior to them, but was considered inferior: I became envious. I was ready to love the whole world, but no one understood me, so I learned to hate. My colorless youth was spent in a struggle with myself and with the world. Fearing mockery, I buried my best feelings at the bottom of my heart: there they died.”