“Why has the pleasure of slowness disappeared? All, where have they gone, the amblers of yesteryear? Where have they gone, those loafing heroes of folk song, those vagabonds who roam from one mill to another and bed down under the stars? Have they vanished along with footpaths, with grasslands and clearings, with nature? There is a Czech proverb that describes their easy indolence by a metaphor: “They are gazing at Gods windows. A person gazing at God’s windows is not bored; he is happy. In our world, indolence has turned into having nothing to do. which is a completely different thing: a person with nothing to do is frustrated, bored, is constantly searching for the activity he lacks.”

(Milan Kundera, Slowness)

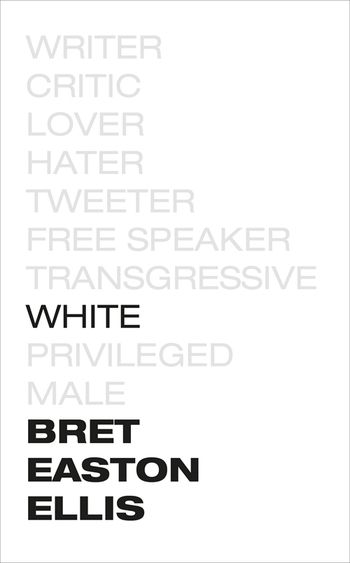

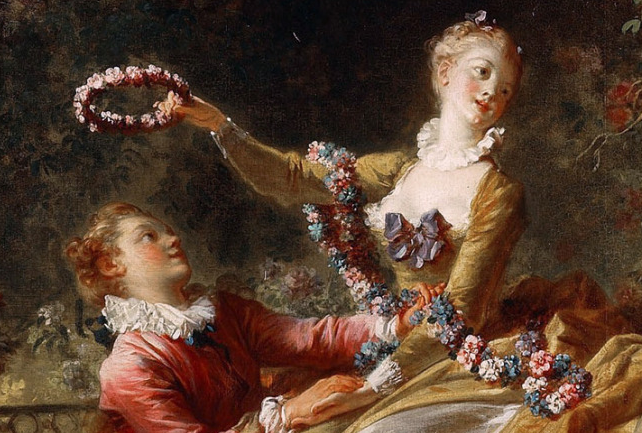

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love – Reverie, 1771

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love – Reverie, 1771

Milan Kundera’s novel “Slowness”, his first novel written in French and not in Czech, was published in 1995. Like all of Kundera’s work, “Slowness” is a philosophical novel. The plot line and the characters serve only as a starting point for the exploration of topics such as slowness, pleasure and hedonism as things of the past, and how the modernity, speed suppress sensuality; modern people have no time for idleness of conquests of love, everything is about the goal and not about the process. To contrast the motifs of slowness vs speed, slow seduction vs rash conquest, Kundera combines two plot lines set in different times. One follows a couple driving in a car to a countryside chateau in France, and the other goes back in past, Kundera takes us back to the wonderful 18th century by retelling a story originally written by Vivant Denons in which the two lovers have a night of slow seduction full of secret symbolism and love language. This is how the novel begins:

“We suddenly had the urge to spend the evening and night in a chateau. Many of them in France have become hotels: a square of greenery lost in a stretch of ugliness without greenery… I am driving, and in the rearview mirror I notice a car behind me. The small left light is blinking, and the whole car emits waves of impatience. The driver is watching for his chance to pass me; he is watching for the moment the way a hawk watches for a sparrow. (…) I check the rearview mirror: still the same car unable to pass me because of the oncoming traffic.Beside the driver sits a woman: why doesn’t the man tell her something funny? why doesn’t he put his hand on her knee? Instead, he’s cursing the driver ahead of him for not going fast enough, and it doesn’t occur to the woman, either, to touch the driver with her hand; mentally she’s at the wheel with him, and she’s cursing me too.

And I think of another journey from Paris out to a country chateau, which took place more than two hundred years ago, the journey of Madame de T. and the young Chevalier who went with her. It is the first time they are so close to each other, and the inexpressible atmosphere of sensuality around them springs from the very slowness of the rhythm: rocked by the motion of the carriage, the two bodies touch, first inadvertently, then advertently, and the story begins. Then begins their night: a night shaped like a triptych, a night as an excursion in three stages: first, they walk in the park; next, they make love in a pavilion; last, they continue the lovemaking in a secret chamber of the chateau.”

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love – The Pursuit, 1771-72

I read “Slowness” five years ago, but this philosophical discussion is something that comes to my mind often and it dawned on me now how connected the slow seduction from Kundera’s novel is with the French Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s series called “Progress of Love” which was originally commissioned by Louis XV’s mistress Madame Du Barry for her pleasure pavilion designed by the architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux. Despite the beauty and vivacious nature of these canvases, they weren’t displayed for a long time in the pavilion, Du Barry soon ended up returning them to the painter. The reason behind her odd dissatisfaction with the master pieces is unknown, perhaps the resemblance between the young lad and the king Louis and the girl and Du Barry was too strong, or perhaps the Rococo spirit of the paintings was going out of fashion and she wanted something less kitschy, more elegant and simple.

I certainly don’t share Madame Du Barry’s opinion. If I could travel in time, I would have persuaded Fragonard to sell the paintings to me and then I would hang them in my luxurious countryside castle and gaze at them and daydream all day long. I just love the elegance and romance in these artworks, the secrecy and the innocence of this love chase. In “The Pursuit” the young lad is handing her a rose, like a true romantic and cavalier. “It’s thy love I want, don’t run away from me!”, his lovely face seems to say. Her answer to this flirtatious proposal is a ballerina-like pose. Kundera directly mentions Rococo art and Fragonard in “Slowness”: “The art of the eighteenth century drew pleasures out from the fog of moral prohibitions; it brought about the frame of mind we call “libertine,” which beams from the paintings of Fragonard and Watteau, from the pages of Sade, Crebillon the younger, or Charles Duclos. It is why my young friend Vincent adores that century and why, if he could, he would wear the Marquis de Sade’s profile as a badge on his lapel. I share his admiration, but I add (without being really heard) that the true greatness of that art consists not in some propaganda or other for hedonism but in its analysis.”

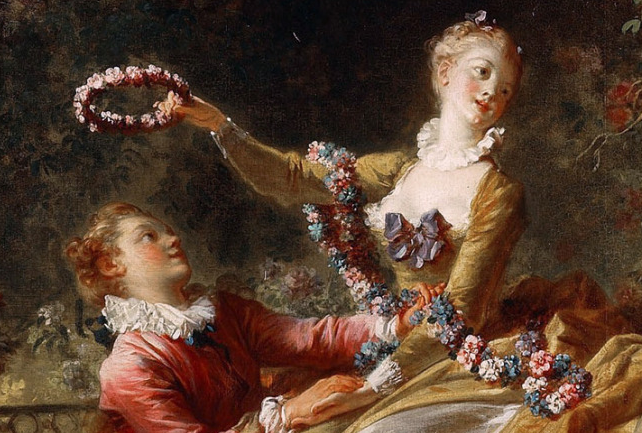

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love – The Secret Meeting, 1771

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love – The Secret Meeting, 1771

Despite faking fear and disinterest in the first canvas, there is our love heroine again, pale and delightful, dressed in a white silk gown. The place of their secret meeting is part-Rococo and part-Romantical; statues and vases are man-made ornaments, but the trees and the mood are summery and romantical. Pink fragrant roses everywhere, birches, serene blue sky and all those tiny light green leaves on the trees. I love the special shade that appear often in Fragonard’s trees, this turquoise, teal shade, the love-child of green and blue. The girl’s face shows concern, as if she had perhaps heard someone’s footsteps approaching. And he had just climbed up the overgrown ladder to the secret walled garden. Can this get more romantical?

I love to enjoy all the little details of the painting such as this letter the girl is holding in her hand. It seems this is the love letter from the young cavalier, filled with sweet words of seduction and details about the secret meeting in the garden which is now taking place.

“First stage: they stroll with arms linked, they converse, they find a bench on the lawn and sit down, still arm in arm, still conversing. The night is moonlit, the garden descends in a series of terraces toward the Seine, whose murmur blends with the murmur of the trees. Let us try to catch a few fragments of the conversation. The Chevalier asks for a kiss. Madame de T. answers: “I’m quite willing: you would be too vain if I refused. Your self-regard would lead you to think I’m afraid of you.”

Everything Madame de T. says is the fruit of an art, the art of conversation, which lets no gesture pass without comment and works over its meaning; here, for instance, she grants the Chevalier the kiss he asks, but after having imposed her own interpretation on her consent: she may be permitting the embrace, but only in order to bring the Chevalier’s pride back within proper bounds.

When by an intellectual maneuver she transforms a kiss into an act of resistance, no one is fooled, not even the Chevalier.”

Jean-Honorá Fragonard, The Progress of Love – The Lover Crowned, 1771-72

The third painting of the series “The Lover Crowned” shows the girl crowning her lover with a crown of pink roses. A crown for the man of her dreams who managed to seduce her. The may be the most vibrant painting out of the series, the colours are just wild; look at all that red and pink of the flowers, the red attire of the lad who seems to be painting a portrait of them, and then the lovely mustard yellow dress the girl is wearing. There isn’t a direct connection between Fragonard’s series “Progress of Love” and the 18th century couple in “Slowness” in terms of content, the story line is different, but it is the element of slow seduction, slow approach to pleasure that unites these two eighteenth century arts. Kundera describes the slowness of one summer night’s seduction, with every detail carefully planed and the pleasure delayed, and Fragonard’s approach is even broader because it portrays the slowness not only of one night’s seduction in a pavilion, but a carefully planned, romantic and innocent game of love which ultimately brings sweet, ripe fruit. Here are some passages from “Slowness”:

“The end of the first stage of their night: the kiss she granted the Chevalier to keep him from feeling too vain was followed by another, the kisses “grew urgent, they cut into the conversation, they replaced it. …” But then suddenly she stands and decides to turn back.

What stagecraft! After the initial befuddlement of the senses, it was necessary to show that love’s pleasure is not yet a ripened fruit; it was necessary to raise its price, make it more desirable; it was necessary to create a setback, a tension, a suspense. In turning back toward the chateau with the Chevalier, Madame de T. is feigning a descent into nothingness, knowing perfectly well that at the last moment she will have full power to reverse the situation and prolong the rendezvous. All it will take is a phrase, a commonplace of the sort available by the dozen in the age-old art of conversation. But through some unexpected concatenation, some unforeseeable failure of inspiration, she cannot think of a single one. She is like an actor who suddenly forgets his script. For, indeed, she does have to know the script; it’s not like nowadays, when a girl can say, “You want to, I want to, let’s not waste time!” For these two, such frankness still lies beyond a barrier they cannot breach, despite all their libertine convictions.”

“I see her leading the Chevalier through the moonlit night. Now she stops and shows him the contours of a roof just visible before them in the penumbra; ah, the sensual moments it has seen, this pavilion; a pity, she says, that she hasn’t the key with her.

As she converses, Madame de T. maps out the territory, sets up the next phase of events, lets her partner know what he should think and how he should proceed. She does this with finesse, with elegance, and indirectly, as if she were speaking of other matters. She leads him to see the Comtesse’s self-absorbed chill, so as to liberate him from the duty of fidelity and to relax him for the nocturnal adventure she plans. She organizes not only the immediate future but the more distant future as well, by giving the Chevalier to understand that in no circumstance does she wish to compete with

They approach the door and (how odd! how unexpected!) the pavilion is open!

Why did she tell him she hadn’t brought the key? Why did she not tell him right off that the pavilion was no longer kept locked? Everything is composed, confected, artificial, everything is staged, nothing is straightforward, or in other words, everything is art; in this case: the art of prolonging the suspense, better yet: the art of staying as long as possible in a state of arousal.”

“By slowing the course of their night, by dividing it into different stages, each separate from the next, Madame de T. has succeeded in giving the small span of time accorded them the semblance of a marvelous little architecture, of a form. Imposing form on a period of time is what beauty demands, but so does memory. For what is formless cannot be grasped, or committed to memory. Conceiving their encounter as a form was especially precious for them, since their night was to have no tomorrow and could be repeated only through recollection. There is a secret bond between slowness and memory, between speed and forgetting.”

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love – Love Letters, 1771-72

The last painting of the series “Love Letters” shows the lovers in a happy union. Again in some beautiful garden with roses and statues. A little dog is lying near the roses, perhaps hinting at the fidelity of the love union, or perhaps just enriching the painting with his cuteness. The girl’s rosy cheeks and pink dress are cuteness overload, and the way the young cavalier is gazing at her is of equal sweetness. Red parasol is a nice Chinoserie hint. But now, to end, I would like to share another quote from the novel “Slowness” about hedonism:

“In everyday language, the term “hedonism” denotes an amoral tendency to a life of sensuality, if not of outright vice. This is inaccurate, of course: Epicurus, the first great theoretician of pleasure, had a highly skeptical understanding of the happy life: pleasure is the absence of suffering. Suffering, then, is the fundamental notion of hedonism: one is happy to the degree that one can avoid suffering, and since pleasures often bring more unhappiness than happiness, Epicurus advises only such pleasures as are prudent and modest. Epicurean wisdom has a melancholy backdrop: flung into the world’s misery, man sees that the only clear and reliable value is the pleasure, however paltry, that he can feel for himself: a gulp of cool water, a look at the sky (at God’s windows), a caress.

Modest or not, pleasures belong only to the person who experiences them, and a philosopher could justifiably criticize hedonism for its grounding in the self. Yet, as I see it, the Achilles’ heel of hedonism is not that it is self-centered but that it is (ah, would that I were mistaken!) hopelessly Utopian: in fact, I doubt that the hedonist ideal could ever be achieved…”

I think the whole philosophy of slowness, pleasure, idleness and hedonism is something we could all use in our hectic, fast modern lives over-bombarded with information and changes, just take things slow and enjoy them.

Tags: 18th century, art, art details, book, Fragonard, hedonism, Jean-Honore Fragonard, libertine, love, Milan Kundera, novel, Pleasure, Progress of Love, romance, seduction, Slowness, writer

“Mal poeta enamorado de la luna”

“Mal poeta enamorado de la luna”