On 24th January 1920, on that sad, cold, grey, winter’s day, it was Saturday I may add, Jewish-Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani died from tubercular meningitis in the Charité Hospital in Paris. There is no beautiful death, the transition to the unknown is bound to be tinged with tragedy, but Modigliani’s death was particularly sad and tragical; so young, so in love, so talented, one step away from receiving recognition. Such an ugly, sad, inhumane way to depart; ill, frail, in a cold room in a hospital bed, the painter who was so humane and who lived for Beauty and devoted his life to it. The next day his young lover Jeanne Hébuterne, who was two months shy from her twenty-second birthday and eight months pregnant with their second child, ended her life tragically by throwing herself from the window of her parents’ flat on the fifth floor; the thought of living without her beloved was unbearable. She was his lover, his muse, his devoted and faithful companion, even in death. Her epitaph on their grave says “Devoted companion to the extreme sacrifice.” Who knows what a new decade would have brought to them both?

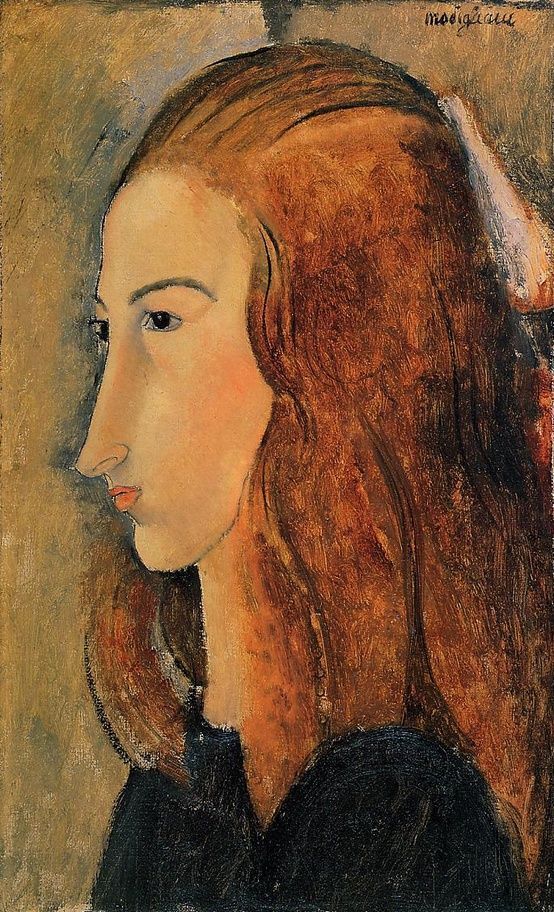

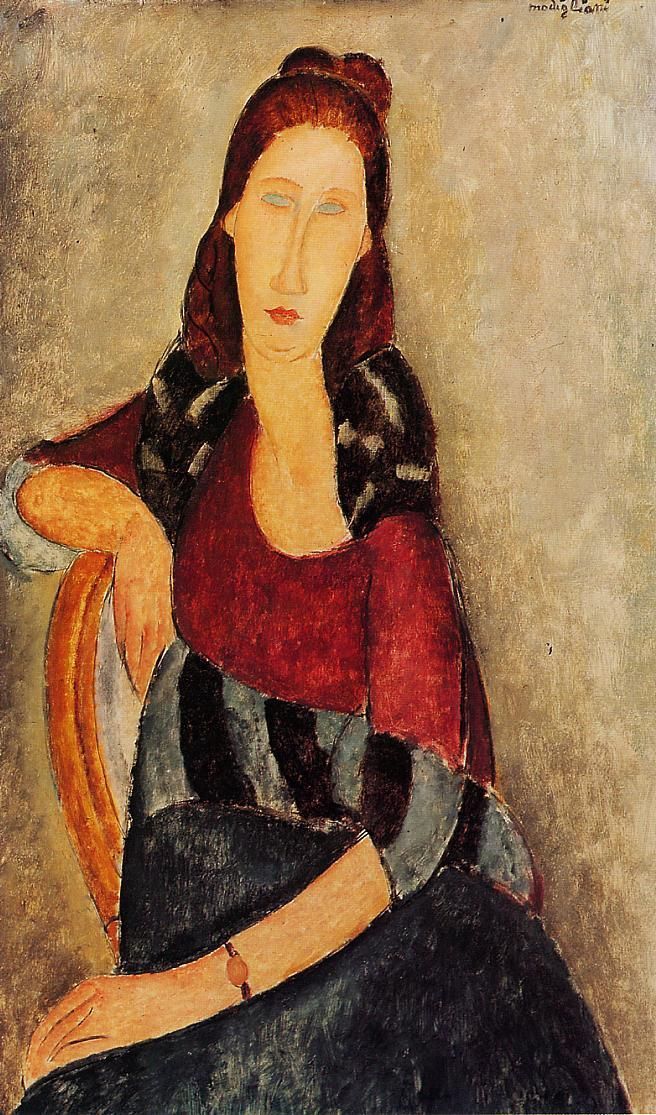

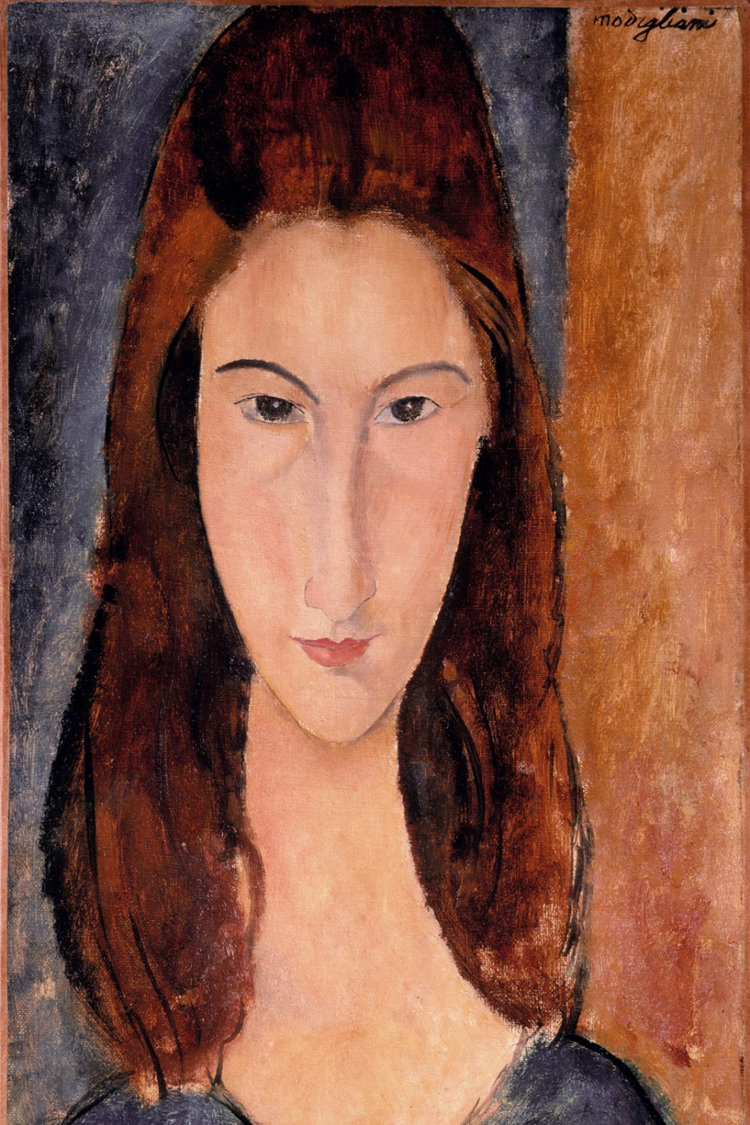

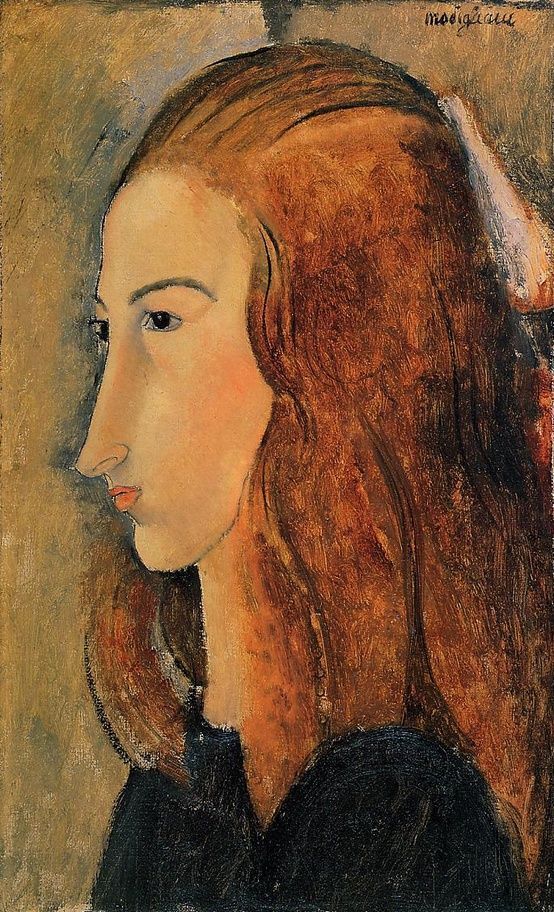

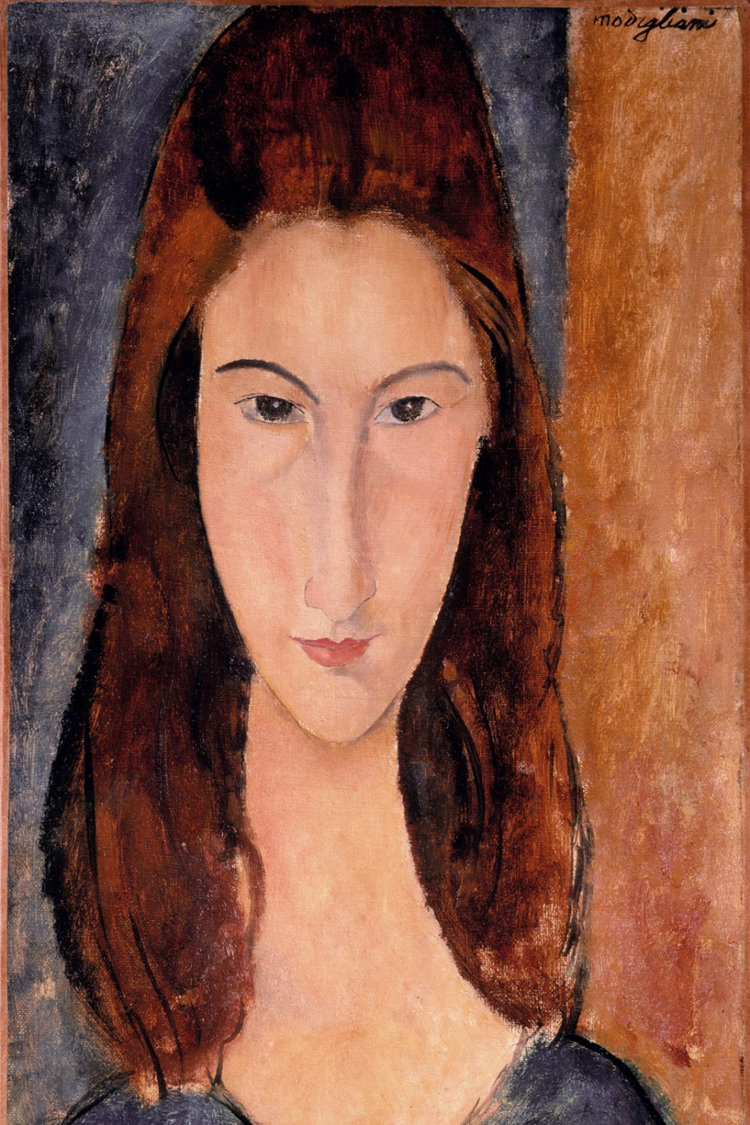

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne, 1918

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne, 1918

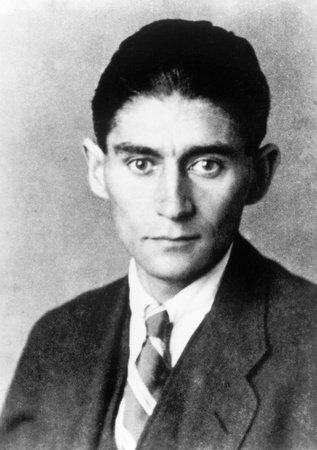

Amedeo was born in July 1884 in a Jewish family in Livorno. His family was well off but around the time he was born, they faced severe financial difficulties. Nonetheless, the dreamy and sickly boy grew up in an environment where literature and philosophy were appreciated. At the age of sixteen he contracted tuberculosis and spent some time in Naples, Capri and Rome, hoping the warm mild weather would soothe his disease. After studying art in Livorno and Florence, Modigliani moved to Venice in 1903 and there he encountered the joys of hashish. Three years later he moved to Paris and encountered the works of Cezanne; the two proved to have a lasting influence on him. His early work shows the influence of Klimt; portraits of femme fatale women with large wide brimmed hats; full, sensuous and thirsty lips and their breasts exposed, a touch of Fauvism in the garish choice of colours, green or blueish for the skin. Cezanne, Cubism and the traditional African masks from Kongo, so popular in the art circles in Paris at the time, all left an impact on his art. Angular, elongated faces with large almond eyes and long noses have found their way from the limestone sculptures to the canvases where finally, after all the influences, his pure artistic instinct, his lyricism, love and poetry emerge.

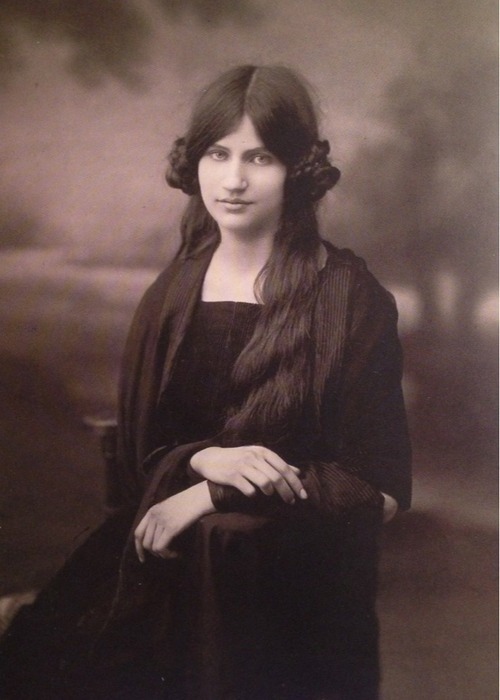

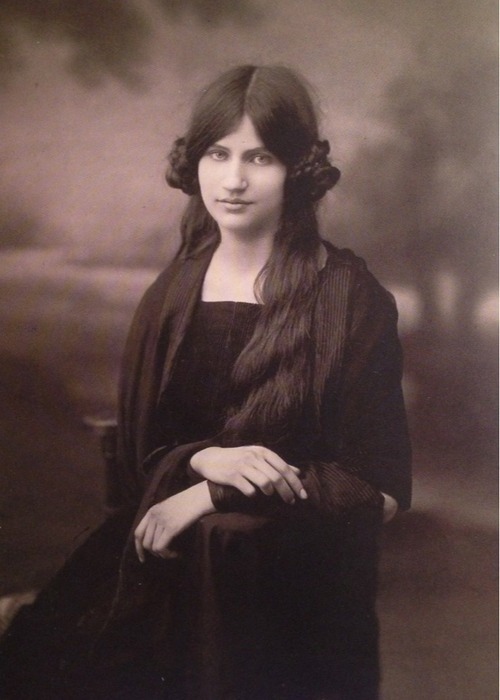

Photographs of Jeanne Hébuterne

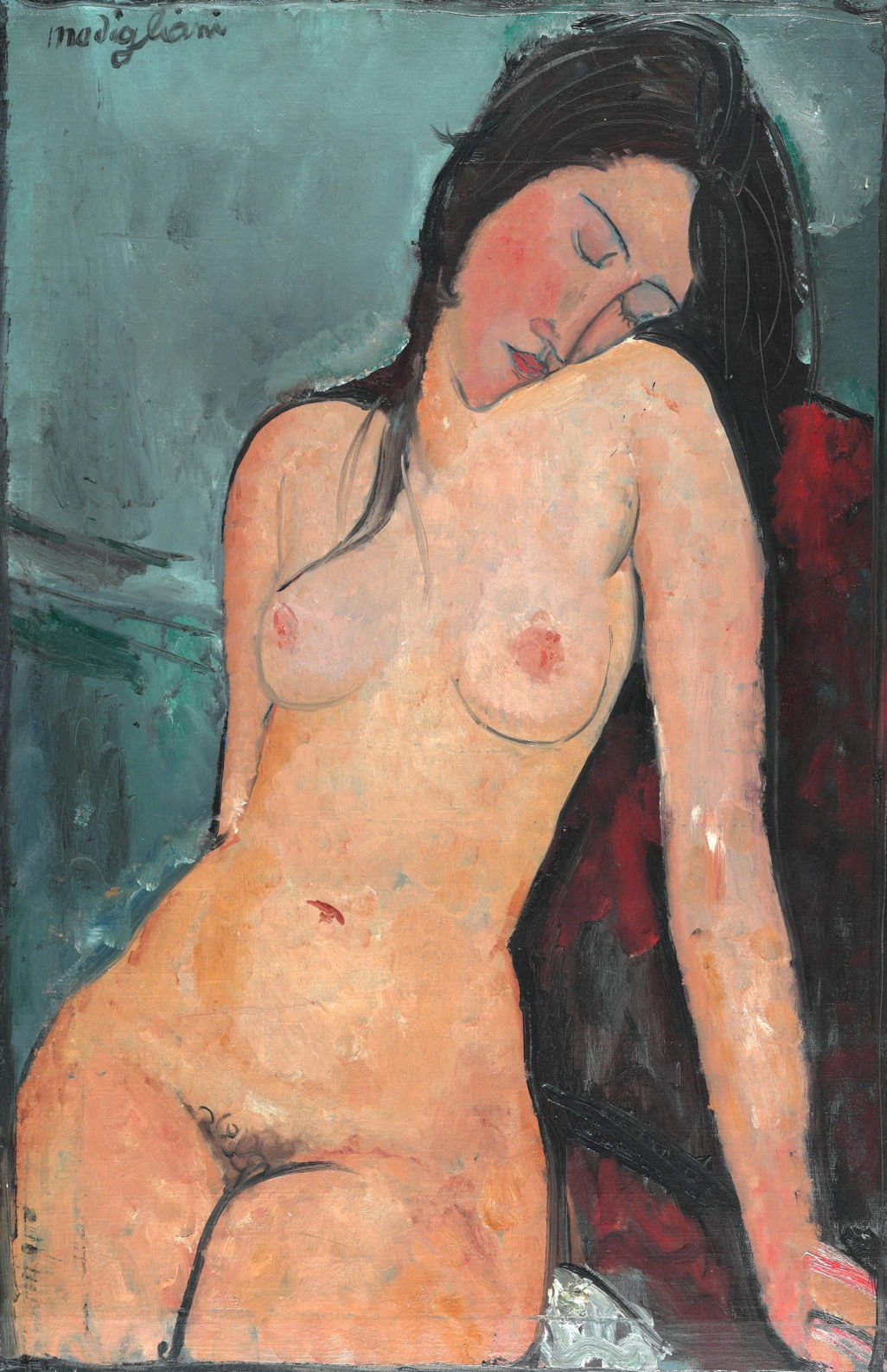

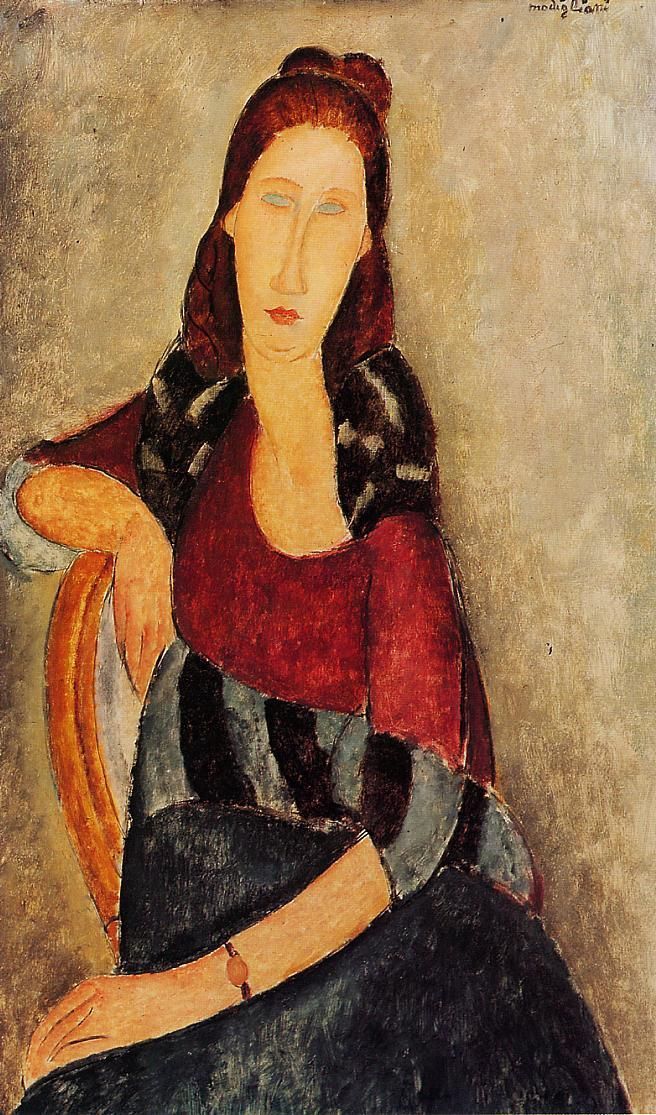

In early 1917 Modigliani finished a series of around thirty nudes. In April 1917, Amedeo met Jeanne Hébuterne, a demure, talented and beautiful schoolgirl who was studying painting at the Académie Colarossi. Ukrainian scultpor Chana Orloff introduced them. Modigliani was no stranger to seduction and it’s easy to see why Jeanne fell for him. He was known in his younger days for his devilish good looks and charms which easily lured women, to his bed and to his canvases. But what was this shy girl from a strict family doing in the wild, free-spirited hippie crowd at Montparnasse? It was her brother André, who also aspired to be a painter, who brought her to the art circles in Montparnasse. The French writer Charles-Albert Cingria described her as “gentle, shy, quiet, and delicate”. Even in the photographs, there is an air of demureness and melancholy around Jeanne; she seems quiet yet passionate, shy but stubborn and strong. She did after all turn her back on the strict bourgeois Catholic upbringing and to the horror of her prim and proper parents moved in with Modigliani soon after meeting him. And what a meeting of souls that must have been! Like Dante and his beloved Beatrice who died young, but inspired his art. Modigliani was an avid reader and always carried his dear homeland Italy in his heart, and during painting sessions he would recite passages from the works of Dante and Petrarca which he knew by heart, and sing arias from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera La traviata.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nude on a Blue Cushion, 1917, oil on linen, 65.4 x 100.9 cm

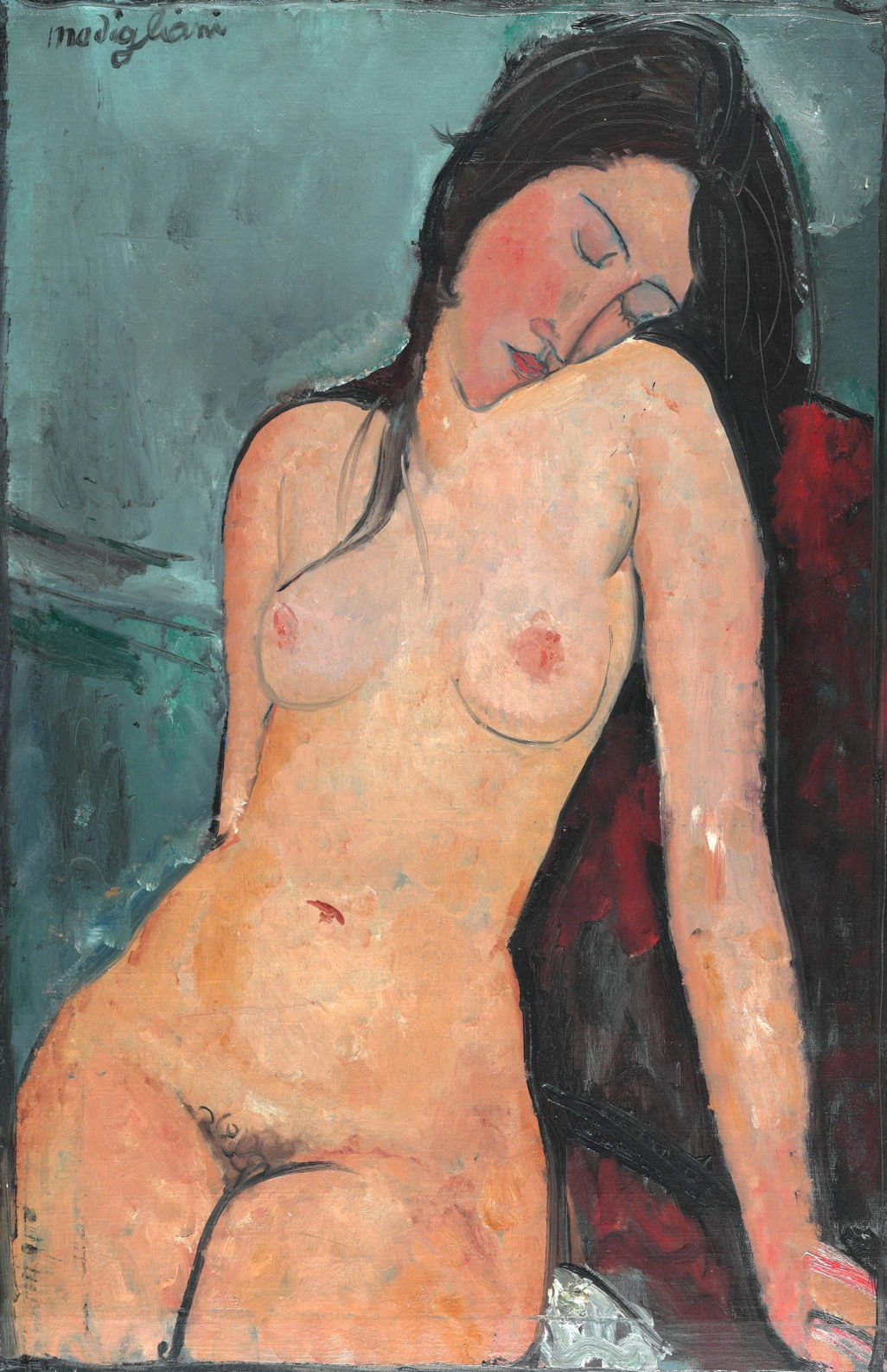

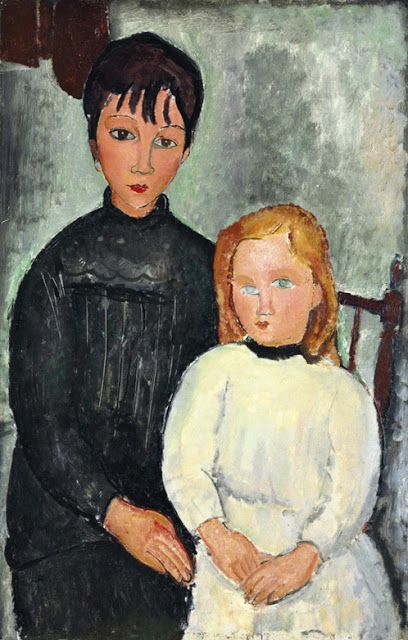

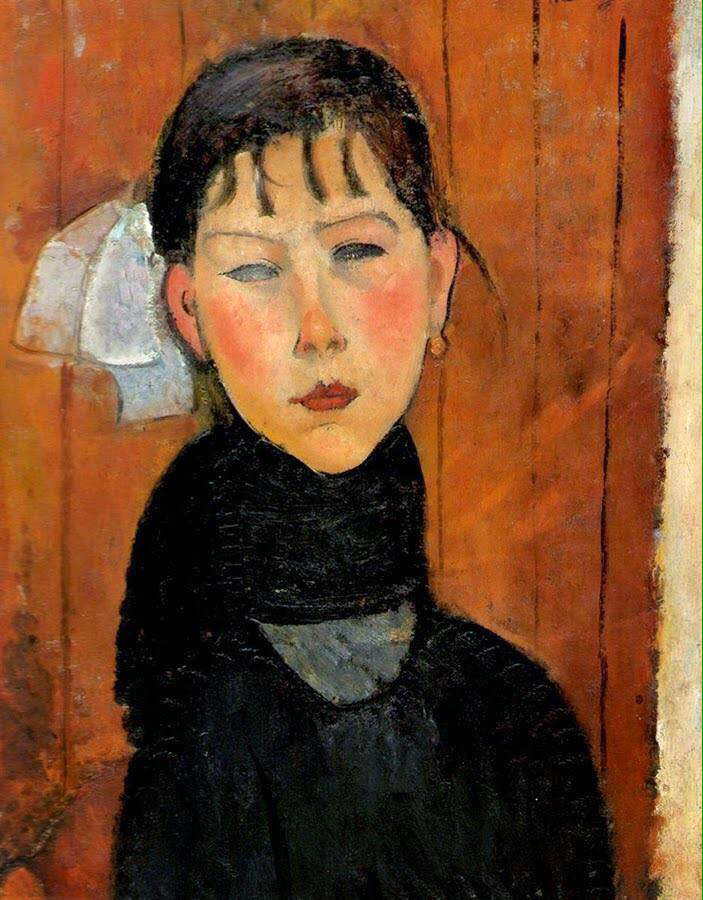

Interestingly, since meeting Jeanne, nudes appear less frequently in Modigliani’s art and her slender figure and face fill canvas after canvas. That’s not to say that Modigliani never painted nudes again, he did, but they don’t seem to dominate his art like they did in previous years. He never painted a nude of Jeanne; perhaps she was too shy to pose like that, or perhaps her body was too sacred to him to share it with the rest of the world, even if it’s on canvas. She was, after all, his future bride, as he wrote in one letter. The nudes he painted in 1917 echo the luminosity and sensuality of Renaissance nudes and the wonderful Venetian sense for colours and tones. All so similar, yet all so different. His oeuvre isn’t a repetitive string of portraits and nudes, but one great gallery of souls. It seems that Modigliani had the gift of transcending the bounds of the flesh, no matter how luminous, soft and pink it was, and painting the soul, connecting soul to soul on a deep, profound, humane level. The same quality of understanding and humanness lingers through the art of another very unique painter whose art, just like Modigliani’s cannot be placed into a specific art movement, and his name is Marc Chagall.

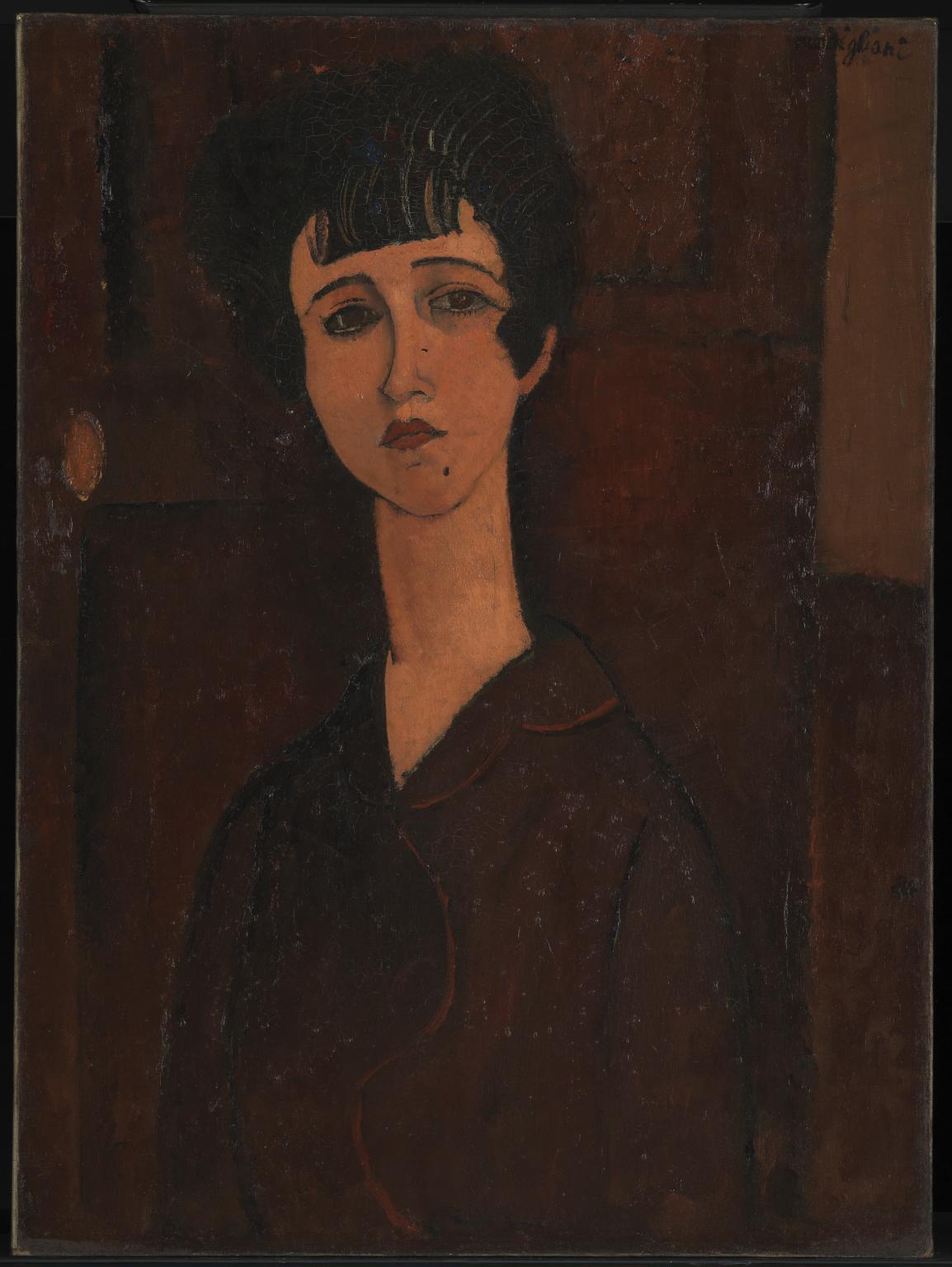

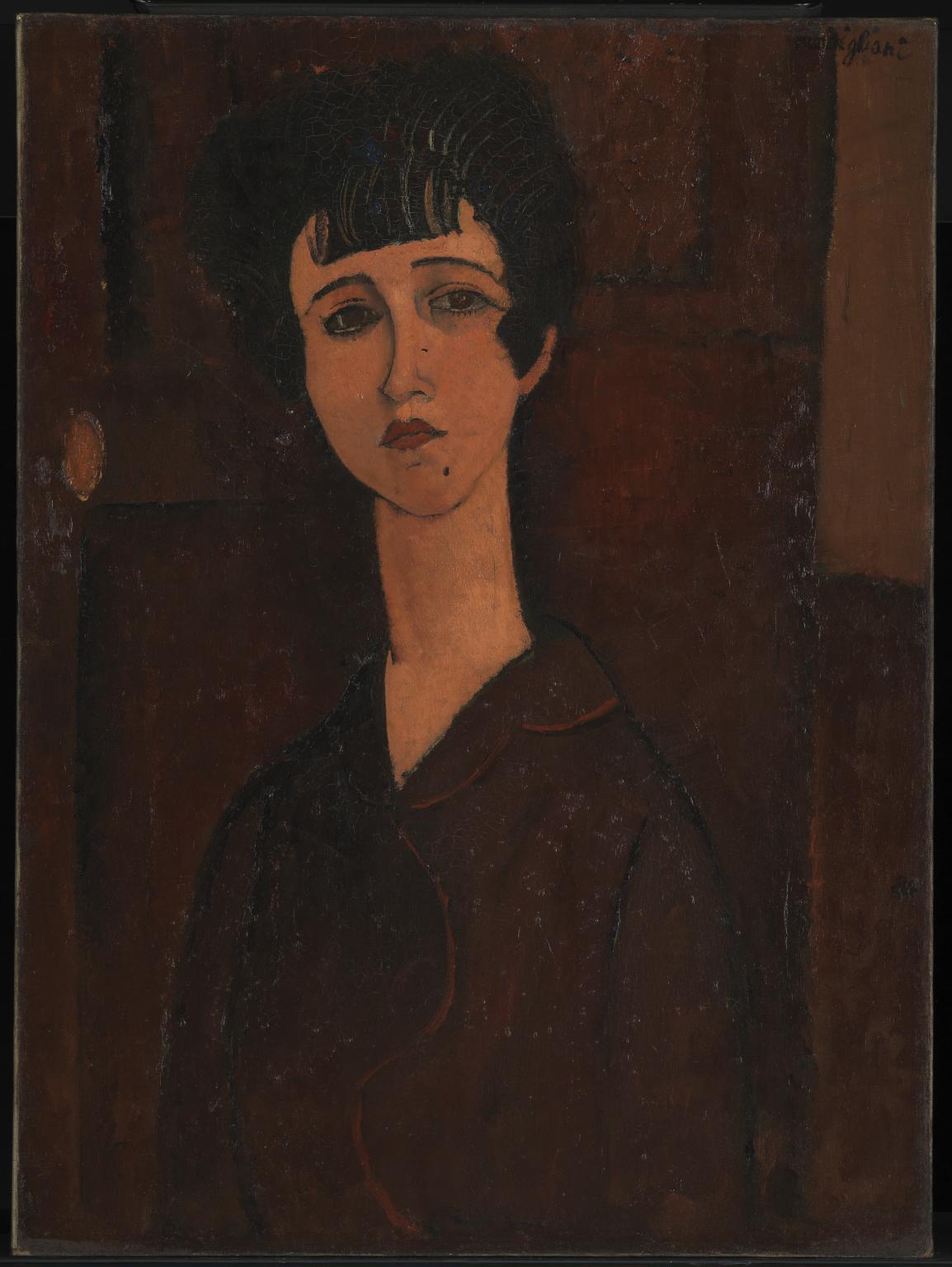

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of a Girl, 1917

Amedeo Modigliani, Reclining Nude, 1917, oil on canvas, 60.6 x 92.7 cm

Amedeo Modigliani, Iris Tree (Seated Nude), 1916, oil on canvas, 92.4 x 59.8 cm

The painting above, “Seated Nude” from 1916 is one of my favourite nudes that Modigliani painted, looking at it now, I am once again filled with ecstasy! Such beauty of the flesh, those warm colours, that pink on her cheek, that mystery in her closed eyes, touches of blue on her eyebrows and her lips, who is this silent muse?

“On that blue velvety Parisian afternoon, Modigliani sat by the window, smoking a cigarette, lost in his thoughts, occasionally glancing at his empty canvas. A nude model is sitting on the chair, behind her a tattered wallpaper, grey wall protruding behind it. Clock is ticking. Rain is beating on the window. Time is passing…. Her long chestnut hair falls over her sunken cheeks. Her eyes are fixated on the wooden floor, but when she lifts her weary eyelids towards Modigliani, aquamarine blue shines through, overwhelming the room, piercing through the greyness of the afternoon. Yes, her eyes are as blue as cornflowers he had seen years before, on one train ride, in the south of France. Fields of cornflowers there were, blue and tender, and amongst them a red poppy was smiling…. yes, blue as cornflowers; Modigliani’s his thoughts lingered on like this…. Her eyelashes are dark, wet from tears, but her face radiates calm resignation. Her lonely blue eyes sense something dark. She looks at Modigliani for a moment, and the next moment she’s lost in her thoughts again. Dreamy veil covers this bohemian abode. Rain is still falling. ‘Modi’, as Modigliani was known, is still smoking the same cigarette. His grey-silvery smoke fills the room like some old tune. A few old, forgotten books lie on the windowsill. Wooden floor is covered with paint flakes at parts. Rain – blue and exhilarating – baths the city. He picks up his brush….

The nude lady is as sad as this rainy afternoon, but he can’t paint her eyes. He feels her sadness, but he can’t bring himself to capture that beautiful aquamarine blueness, because he does not yet know her soul.”

(An excerpt from my older post)

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu Couche, 1918

These luscious, sensuous nudes were exhibited on Monday, 3rd December 1917 in the gallery of Berthe Weill. Modigliani was thirty-three years old, and this was the first and the last exhibition of his life. Many Parisians were drawn to the gallery that evening, but unfortunately for Berthe and Modigliani, the gallery was situated opposite the police station and seeing the gregarious curious crowd in front of the gallery made the policemen curious too. They instantly showed up and were scandalized by the art they had seen and instantly demanded Berthe to remove them, or else they would be confiscated. It was the pubic hair which scandalised the policemen especially. These narrow minds judging such a wonderful artist, very sad, especially since Modigliani devoted his life to Beauty. The scandal and failure of the exhibition didn’t plague his spirit for long. Love had entered in Modigliani’s life in the form of a shy, sweet Jeanne and Modigliani was very inspired and very prolific, filling canvas after canvas with her face, serious with direct gaze and large blue eyes. Apart from Jeanne, Modigliani painted many other neighbourhood faces, pretty melancholy street-urchins, but he painted them with poetry and compassion. He spent a great deal of 1918 and 1919 in Nice where he met the old Renoir, and he painted some landscapes while there, a genre uncommon for him. Their daughter Jeanne was born in Nice on 29th November 1918. After returning to Paris in late 1919, Modigliani continued with his melancholy portraits, but sadly he died soon afterwards, on the 24th January 1920. Now let us take a look at some wonderful portraits of Jeanne and other girls!

Amedeo Modigliani, Jeanne Hebuterne, 1919

Amedeo Modigliani, Jeanne Hebuterne with Hat and Necklace, 1917

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne, Seated, 1918

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne, 1918

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne in a Hat, 1919

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne, 1917

Amedeo Modigliani, Petite Lucienne, 1916

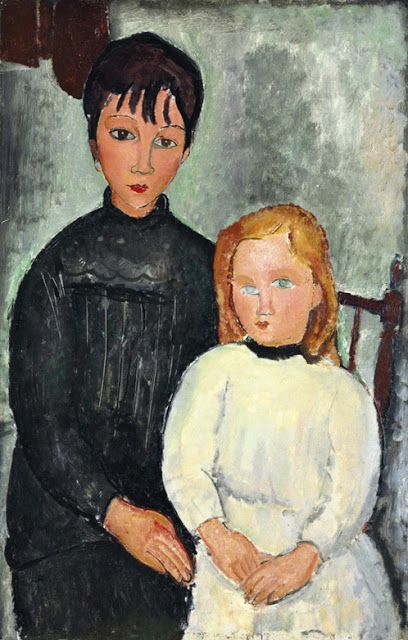

Amedeo Modigliani, Two girls, 1918

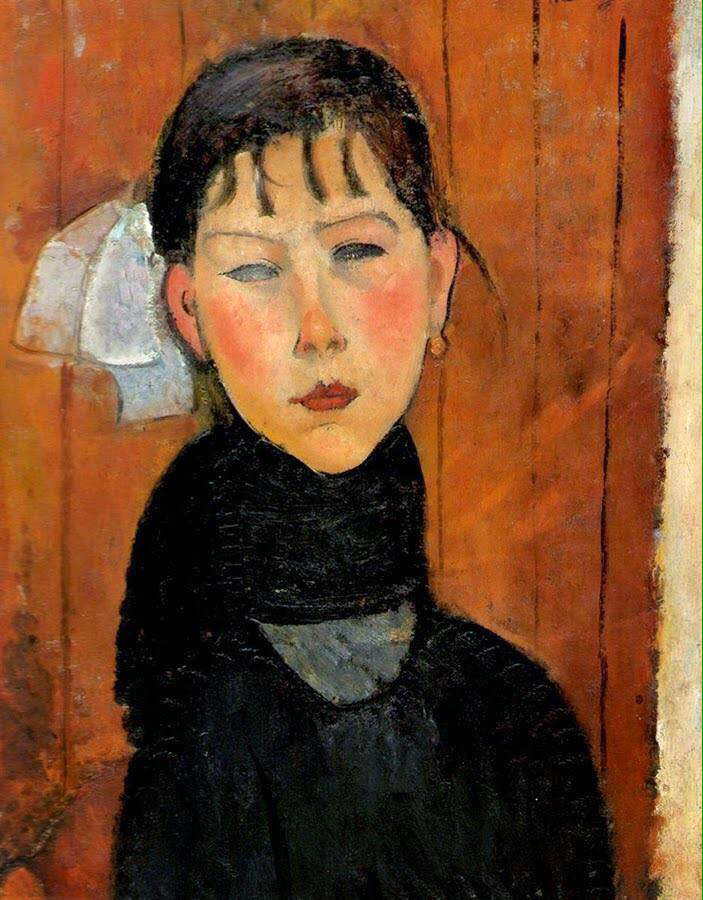

Amedeo Modigliani, Marie, 1918

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Paulette Jourdain, 1919

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne, 1918

Tags: 1910s, 1920, Amedeo Modigliani, art, Death, Jeanne Hebuterne, Jewish-Italian artist, love, lover, lyrical, Modigliani, Muse, Painting, Paris, passion, poetic, portrait

Alphonse Mucha, Girl With a Plate With a Folk Motif, 1920

Alphonse Mucha, Girl With a Plate With a Folk Motif, 1920