“You are the knife I turn inside myself; that is love. That, my dear, is love.” – this is what Kafka wrote to the mysterious Milena, and isn’t this sentence alone, with Kafka’s vibrant expressionistic definition of love, enough to lure you into reading the book?

The lucky lady: Milena Jesenská. Kafka wrote to her: “Written kisses don’t reach their destination, rather they are drunk on the way by the ghosts.”

The lucky lady: Milena Jesenská. Kafka wrote to her: “Written kisses don’t reach their destination, rather they are drunk on the way by the ghosts.”

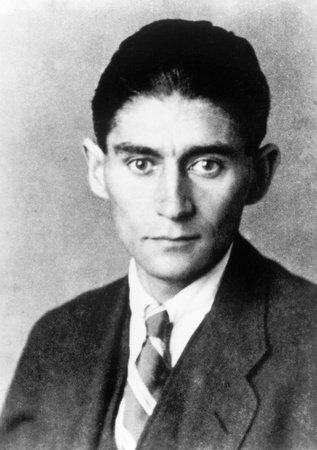

In 1920, Franz Kafka and Milena Jesenská began a love affair through letters. Kafka is a well-known figure in the world of literature, but who was Milena? Milena was a twenty-three year old aspiring writer and translator who lived in Vienna in a marriage that was slowly falling apart. She recognised Kafka’s writing genius before others did. Despite the distance, despite the turbulent sea with insurmountable waves between Kafka in Prague and Milena in Vienna, the two developed an intense and intimate relationship. They stripped the masks of their bourgeois identities and bared their souls. The correspondence started when Milena wrote to Kafka and asked for a permission to translate his short story “The Stoker” from German to Czech. Such a simple request and formal demand very soon turned into a series of passionate and profound letters that Milena and Franz exchanged from March to December 1920. Kafka often wrote daily, often several times a day; such was his devotion. This is what he tells her: “and write me every day anyway, it can even be very brief, briefer than today’s letters, just 2 lines, just one, just one word, but if I had to go without them I would suffer terribly.” The letters are interesting from a linguistic point of view as well; Kafka wrote his letters in German while Milena wrote most of hers in her mother tongue, Czech. I found it really interesting to know that Kafka was fluent in Czech.

Although Kafka confided to Milena about his anxieties, fears, loneliness, it wasn’t all honey and roses; Kafka’s letters revealed the extent of his anguish caused by Milena, the sleepless nights, and the futile situation of their love. Milena haunted his thoughts, but he wasn’t the only one to suffer. In the introduction to letters Williy Haas describes Milena as a caring friend inexhaustible in her kindness and a desire to help. Kafka later writes to her calling her a ‘savior’. Passionate, vivacious and courageous, Milena suffered greatly nonetheless because of him, as Kafka said himself: “Do you know, darling? When you became involved with others you quite possibly stepped down a level or two, but If you become involved with me, you will be throwing yourself into the abyss.” She must have known that herself, and yet she chose to sink because ‘lust for life’ was part of her personality, and pain and rapture go hand in hand. Haas also reminds us that Dostoyevsky was her favourite writer and that we also mustn’t forget the propensity towards pain which is so typical for Slavic women. Slavic soul is a deep and dark place, one you better not wander into out of mere curiosity. It is almost hard to imagine how two such strong, profound, dark souls could even live a simple life together. Their relationship was of a hot-cold character; intense at one moment because their minds were alike, then alienating the other because of the distance. When one side was attached, the other cooled down, and vice versa. When she yearned to see him in Vienna, he was reluctant; when he wanted her to divorce her husband and come live with him, she wasn’t keen to do so.

They were very different in age and personalities but they fit perfectly as two hands when clasped together. No other woman entranced Kafka so much, and despite the abrupt sad end of their passionate correspondence I still think Milena was just what he needed. Here are two quotes which discuss their age difference: “It took some time before I finally understood why your last letter was so cheerful; I constantly forget the fact that you’re so young, maybe not even 25, maybe just 23. I am 37, almost 38, almost older by a whole short generation, almost white-haired from all the old nights and headaches.” He also tells her: “You see, the peaceful letters are the ones that make me happy (understand, Milena, my age, the fact that I am used up, and, above all, my fear, and understand your youth, your vivacity, your courage.”

“I miss you deeply, unfathomably, senselessly, terribly.”

They met only two times in real life; on the first occasion they spent four days together in Vienna in June 1920, and the second time, in August 1920, they only met briefly in Gmünd on the Austrian-Czech border. It was Kafka who broke off the relationship because the situation seemed too pointless; they lived far away and Milena wasn’t willing to abandon her husband. They exchanged a few more letters throughout 1922 and 1923, but they were more reserved in nature and fewer in number. He tells her: “Go on caring for me.” In 1924, Kafka died. Milena died twenty years later, ill and alone in a concentration camp.

And now my favourite quotes:

“Yours

(now I’m even losing my name – it was getting shorter and shorter all the time and is now: Yours)”

“I have spent all my life resisting the desire to end it.”

“It’s a little gloomy in Prague, I haven’t received any letters, my heart is a little heavy. Of course it’s impossible that a letter could be here already, but explain that to my heart.”

“That’s not the point, Milena, as far as I’m concerned you’re not a woman, you’re a girl, I’ve never seen anyone who was more of a girl than you, and girl that you are, I don’t dare offer you my hand, my dirty, twitching, clawlike, fidgety, unsteady, hot-cold hand.”

“All writing seems futile to me, and it really is. The best would probably be for me to go to Vienna and take you away; I may even do it, although you don’t want me to.” (9 July 1920)

“I wanted to excel in your eyes, show my strength of will, wait before writing you, first finish a document, but the room is empty, no one is minding me – it’s as if someone said: leave him alone, can’t you see how engrossed he is in his own affairs, it’s as if he had a fist in his mouth. So I only wrote half a page and am once again with you, lying on this letter like I lay next to you back then in the forest.” (16 July 1920)

“With my teeth clenched, however, and with your eyes before me I can endure anything: distance, anxiety, worry, letterlessness.” (16 July 1920)

“I am caught in a tide of sorrow and love which is carrying me away from writing.” (17 July 1920)

This one is particularly beautiful and profound, straight from the heart. When I first read it, I loved the fact that he needs solitude and time to think about Milena, but then when I read it the second time, something else struck me: when he says his office job is boring, his flat is stupid, but he feels he must not complain about his everyday reality because Milena is part of it too, and the gratefulness he feels for that: this moment which belongs to you:

“A slight blow for me: a telegram from Paris, informing me that an old uncle of mine (…) is arriving tomorrow evening. It is a blow because it will take time and I need all the time I have and a thousand times more than all the time I have and most of all I’d like to have all the time there is just for you, for thinking about you, for breathing in you. My apartment is making me restless, the evenings are making me restless, I’d like to be someplace different and I’d prefer it if the office didn’t exist at all; but then I think that I deserve to be hit in the face for speaking beyond the present moment, this moment, which belongs to you.” (6 July 1920)

“…and I am here just like I was in Vienna and your hand is in my own as long as you leave it there.” (29th July 1920)

“You’re always wanting to know, Milena, if I love you, but after all, that’s a difficult question which cannot be answered in a letter (not even in last Sunday’s letter). I’ll be sure to tell you the next time we see each other (if my voice doesn’t fail me.” (30 July 1920)

“Milena among the saviors! Milena who is constantly discovering in herself that the only way to save another person is by being there and nothing else. Moreover, she has already saved me once with her presence and now, after the fact, is trying to do so with other, infinitely smaller means. Naturally, saving someone from drowning is a great deed, but what good is it if the savior then sends the saved a gift-certificate for a swimming course?” (31 July 1920)

“And how can I fly if we are holding hands? And what good is it for us to both fly away? And besides – this is actually the main thought of the above – I’ll never go so far away from you again.” (31 July 1920)

“I am dirty, Milena, endlessly dirty, that is why I make such a fuss about cleanliness. None sing as purely as those in deepest hell; it is their singing we take for the singing of angels.” (26 August 1920)

“Why, Milena, do you write about our common future which will never be, or is it that why you write about it? (…) Few things are certain, but one is that we’ll never live together, share an apartment, body to body, at a common table, never, not even in the same city. (…) Incidentally, Milena, you must agree when you examine yourself and me and take soundings of the “sea” between “Vienna” and “Prague” with its insurmountably high waves.” (Prague, September 1920)

***

Kafka’s “Letters to Milena” left a scar of Beauty on my soul. I enjoyed the book tremendously. Since Kafka as a person and his work are both pretty dark, I was amazed to see a tenderer, loving side of his personality, and to be inside his mind. I started reading the book thinking ‘this is interesting’, but as I turned the pages I felt more and more drawn in by his words. It’s hard to explain, but they touch me right in the heart even though they were not meant for me, just like a sewing needle pierces your skin and causes a sharp and burning pain which lasts for a second but leaves an echo. Kafka’s words, in the letters as well as in his stories, are simple at first reading, but they stir the waves inside me after I close the book. I hope this post inspires you to read the book. As of 2017, I have been immensely interested in letters, diaries and memoirs. The depth of feelings and the aspect of sincerity and intimacy in those literary forms just wins me over. So, if you have any suggestion about correspondences I should read, feel free to tell me.