“All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.”

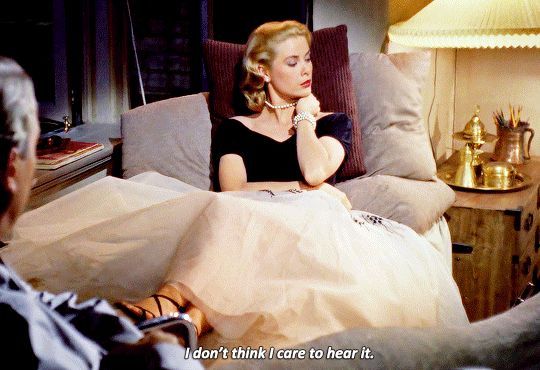

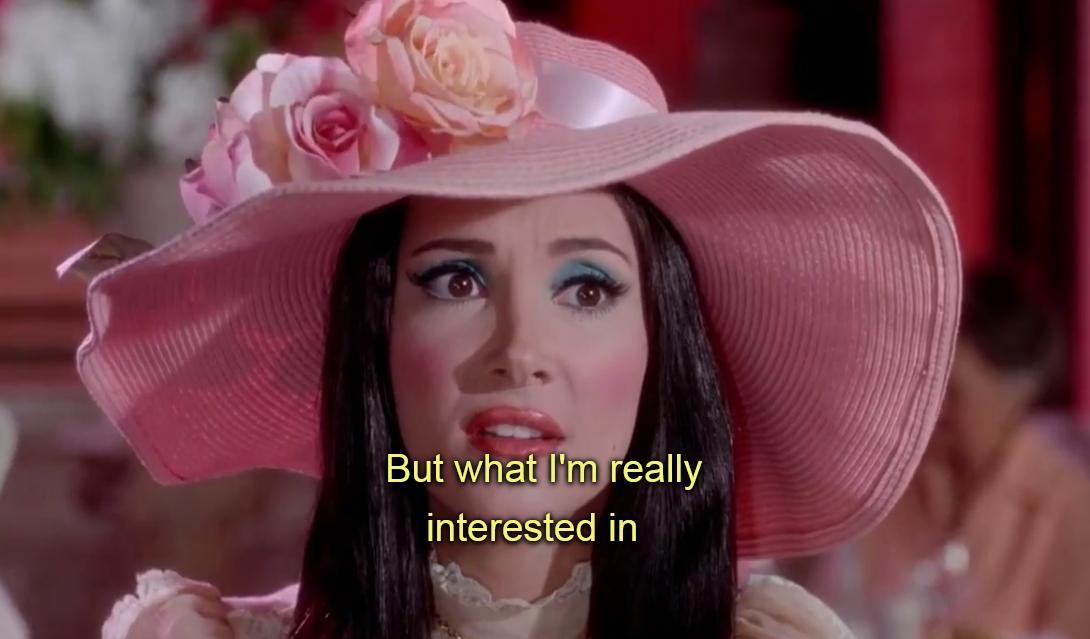

Arthur Rackham, “The Oval Portrait,” Tales of Mystery and Imagination, 1935

Arthur Rackham, “The Oval Portrait,” Tales of Mystery and Imagination, 1935

One of my favourite stories by Edgar Allan Poe is “The Oval Portrait”; it’s short and sweet, and its main theme is art and the artist. When, by serendipity, I found this gorgeous illustration of the story by Arthur Rackham the other day I knew that it was a sign from the universe to write about it today because today is the anniversary of Poe’s death. The doomed poet died in Baltimore on the 7th October 1849 at the age of forty; the last days of his life were as mysterious as the man himself. In a wonderful biography, Peter Ackroyd wonders: “No one knew where he had been, or what he had done. Had he been wandering, dazed, through the city? Had he been enlisted for the purposes of vote-rigging in a city notorious for its political chicanery? Had he suffered from a tumour of the brain? Had he simply drunk himself into oblivion? It is as tormenting a mystery as any to be found in his tales.”

The mystery of the story “The Oval Portrait” is, as the title suggests, about a portrait of a beautiful woman. The story starts as a Gothic tale with an unnamed narrator who seeks safe shelter form the rain in an old castle. Before falling asleep in one of the old bedroom he becomes enamored with a portrait of a beautiful young woman on the wall. The plot quickly switches from the narrator to the story about the portrait itself and its history, again there’s “the most poetic topic in the world” according to Poe himself; the death of a beautiful woman, a pale wistful bride who, adoring and obedient, died as a sacrifice for her mad artist husband who cared for nothing else but his art. Arthur Rackham was a very prolific and imaginative artist so I am not surprised that he portrayed this scene from the story so wonderfully.

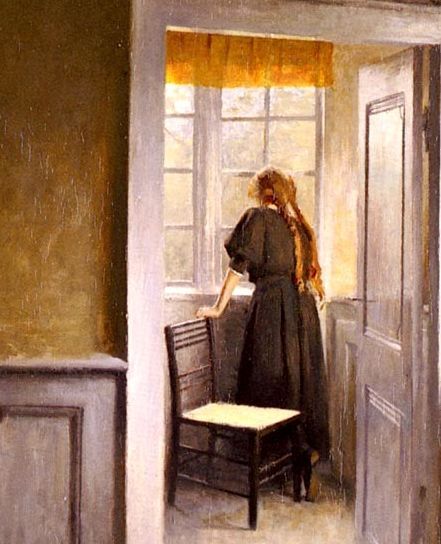

Rackham portrayed the tower-chamber setting accurately and the high windows only add to the lonesome feeling of the tower. The light of the day is entering the chamber sparingly. We cannot see the forests and moors around the castle. Instead the space feels hermetic and secluded from the outside world. It’s almost like a theatre stage; the painter, the pale model and the Portrait are the only figures on this stage of life. A stone wall on one side and the draped curtains on the other are the background to the scene. Rackham depicts the background with equal detail as he does the figures; the wooden floor, the stone wall, the shadow of the easel and the gorgeous fabric are all so detailed and life-like. The portrait in Rackham’s illustration seems unfinished, but perhaps the vagueness is the desired look. Anyhow, the lady’s face in the portrait does look like the face that might haunt a man at night if he saw it on the wall of his chamber, stranded in the desolate castle while the rain is beating against the windows.

The costumes that the Painter and the damsel are wearing bring back the spirit of gone-by days. The Painter’s necklace and his hair are reminiscent of Van Dyck’s portraits, and the lady’s golden ringlets, pearl necklace and her silk dress with puffed sleeves look as if they were stolen from the royal portraits of Louis XIV’s mistresses. Rackham chose to depict the last and the most thrilling part of the story; the moment when the Painter finishes his portrait and realises that his beautiful young wife is death, or, to quote the story directly: “the painter stood entranced before the work which he had wrought; but in the next, while he yet gazed, he grew tremulous and very pallid, and aghast, and crying with a loud voice, ‘This is indeed Life itself!’ turned suddenly to regard his beloved:- She was dead!”

Here is the last part of the story which describes the story behind it:

“She was a maiden of rarest beauty, and not more lovely than full of glee. And evil was the hour when she saw, and loved, and wedded the painter. He, passionate, studious, austere, and having already a bride in his Art; she a maiden of rarest beauty, and not more lovely than full of glee; all light and smiles, and frolicsome as the young fawn; loving and cherishing all things; hating only the Art which was her rival; dreading only the pallet and brushes and other untoward instruments which deprived her of the countenance of her lover. It was thus a terrible thing for this lady to hear the painter speak of his desire to pourtray even his young bride. But she was humble and obedient, and sat meekly for many weeks in the dark, high turret-chamber where the light dripped upon the pale canvas only from overhead.

But he, the painter, took glory in his work, which went on from hour to hour, and from day to day. And be was a passionate, and wild, and moody man, who became lost in reveries; so that he would not see that the light which fell so ghastly in that lone turret withered the health and the spirits of his bride, who pined visibly to all but him. Yet she smiled on and still on, uncomplainingly, because she saw that the painter (who had high renown) took a fervid and burning pleasure in his task, and wrought day and night to depict her who so loved him, yet who grew daily more dispirited and weak. And in sooth some who beheld the portrait spoke of its resemblance in low words, as of a mighty marvel, and a proof not less of the power of the painter than of his deep love for her whom he depicted so surpassingly well.

But at length, as the labor drew nearer to its conclusion, there were admitted none into the turret; for the painter had grown wild with the ardor of his work, and turned his eyes from canvas merely, even to regard the countenance of his wife. And he would not see that the tints which he spread upon the canvas were drawn from the cheeks of her who sate beside him. And when many weeks bad passed, and but little remained to do, save one brush upon the mouth and one tint upon the eye, the spirit of the lady again flickered up as the flame within the socket of the lamp.

And then the brush was given, and then the tint was placed; and, for one moment, the painter stood entranced before the work which he had wrought; but in the next, while he yet gazed, he grew tremulous and very pallid, and aghast, and crying with a loud voice, ‘This is indeed Life itself!’ turned suddenly to regard his beloved:- She was dead!”