“All changes pass me like a dream,

I neither sing nor pray;

And thou art like the poisonous tree

That stole my life away.”

(Elizabeth Siddal, “Love and Hate”)

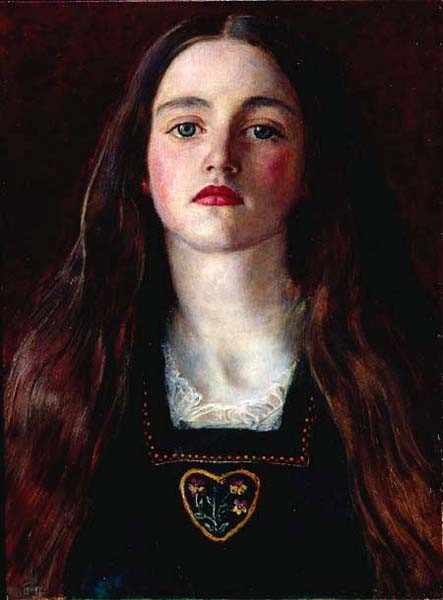

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, A Portrait Sketch of Elizabeth Siddal, c. 1850s

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, A Portrait Sketch of Elizabeth Siddal, c. 1850s

Elizabeth Siddal, a famous and doomed Pre-Raphaelite muse and a lover of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was born on 25th July 1829 in London. She died in February 1862 at the age of 32, but had she been a vampire, which I suspect she might as well be, she would have been 190 years old today, a fairly young age for a vampire. I am thinking about her these days; about her beauty, her poems and paintings, and also about the exhumation of her body led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti who wanted to get back the poems he had buried with her. An image of her coffin being opened, and her long red hair revealed by the moonlight, silence of the graveyard, the eeriness…. It is easy to imagine why this event inspired young Bram Stoker for his character Lucy in “Dracula”.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti; Elizabeth Siddal, study for ‘Delia’ in the ‘Return of Tibullus’, 1853

Nonetheless, the main thing on my mind these days is how mysterious the person of Elizabeth Siddal actually is. Who was she really? How little we know of her and how the rest is painted in our imaginations. When I first read about her years ago, I was met with a very idealised image of a beautiful, quiet and melancholy young woman who modeled for the Pre-Raphaelites, used laudanum and was plagued with sadness and Rossetti’s infidelities; she seemed almost like a martyr, the one who suffered, the one who was tormented. I think part of it was true, she was a struggling working class girl who wanted more from life, materially and spiritually; she wanted to rise above the circumstance that she was born into, she wanted to learn and grow intellectually, but also she wanted a finer, more comfortable life; “a servant to lay the fire in the morning, theater tickets, a paisley shawl.” (Gay Daly, Pre-Raphaelites in Love)

The promises that Rossetti gave, he did not fulfill; he was impulsive, careless with money, had a wandering eye and was strangely very hesitant to marry her, and it is easy to understand why it brought her so much anguish, especially in the Victorian era when her status of artist’s model and a lover closed many doors for her and gave her an unenviable place in society. Artistically, she was always in Rossetti’s shadow and she could never have dreamed that her paintings of her poems would be as appreciated as his were. All these things indeed make her a sufferer, but I feel like there is another side of her that no one tends to talk about, for it would ruin her untainted image of a martyr and an angel. She may be a mysterious muse, but she is not a perfect one for sure.

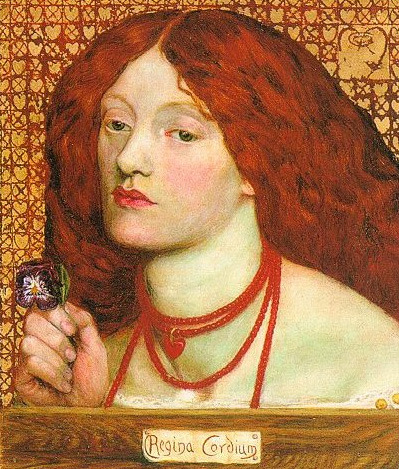

Regina Cordium – Rossetti’s Marriage portrait of Elizabeth Siddal, 1860

Blinded by her beauty; her long coppery red hair, pale complexion, fragile frame, and eyes that changed colour from green to grey, Rossetti was bewitched at first sight by this strange girl who worked in a hat shop. She was equally charmed, but as ideal the start of their relationship was, its course was a turbulent one with lots of drama, anger, tears and manipulation. Lizzie was known for her frail health, but it is very interesting how her health changed according to the occasion. She could feel perfectly well in the morning, but as soon as Rossetti was getting ready to head into town, hang out with other people, she would suddenly feel unwell and if she would get him to stay at home that day, her health was fine.

She was emotionally manipulative without a doubt and, to me, she seems like a very moody and miserable woman and I am not surprised that Rossetti would want to go out and spend time with merrier, more carefree women. In her book “Lizzie Siddal: The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel” Lucinda Hawksley writes that “both shared a destructively jealous need to be the most important figure in their – or, indeed, any relationship.” And also: “When one – or both – of them was unhappy, ill, depressed or jealous, they made one another’s lives hellish. (…) Self-destructive and self-loathing at times, as well as being arrogant about their abilities, both must have been extremely difficult to live with.” She was happy at the beginning of their relationship, in times when Ophelia was painted but as their life went on, she started using her frail health as a way of getting things she wanted, mostly from Rossetti but also from other people. Again, here is an interesting passage from Lucinda Hawksley’s book: “It is interesting to see how often Lizzie’s health coincided with Rossetti’s affections being taken up by other woman. By his refusal to marry her, Rossetti had forced her to blackmail him emotionally and she used every opportunity to do so. At the start of their relationship it seems the balance of power was very much in his favour as she struggled to prevent him from tiring of her, but by the end of her life she had become overtly manipulative and controlling, to the point that his friends claimed he shrank when she spoke to him, always expecting a rebuke or for her to sink dangerously into illness, blaming him wordlessly for its onslaught.”

As if her “illnesses” weren’t enough, Lizzie would stop eating to get her point across, or sink into periods of depression and self-loathing. Mrs Siddal was also known for being aloof and quiet when in company with other people, and I can well understand that because I am somewhat similar, but I think it was just a means for her to show her disdain and disinterest, and to emphasise the mysteriousness about her that she loved nurturing. She was known for petty jealousies and acted as if she were better than other working class models who might have been prostitutes also, for example Hunt’s model Annie Miller.

John Everett Millias, Ophelia, 1852

With all that said, I will also add that I love Lizzie and I am not being hateful here, I am in fact endlessly captivated by her short tragical life, her mysteriousness, and her connection to the Pre-Raphaelites. I love her poetry and empathise with her verses. But I have to say that she is no angel and I hate people idealising her while at the same time bashing on Rossetti for being this or that. She was manipulative, jealous, strategically ill when necessary, miserable, depressed, perhaps impossible to satisfy at times, and I don’t see why that is not mentioned so often. She was an artist’s muse and a model, that position alone ought to have made her feel like she were the luckiest girl in the world. Just think of Poe’s submissive little wife Virginia and her perfect adoration for the doomed poet. I think Lizzie didn’t need an ancient curse like the Lady of Shalott to bring her death because Lizzie seems capable enough of bringing her own doom.

Now, I don’t want to judge her harshly because I have not met her, but no matter how much I read about her, I am still left with a feeling of mysteriousness. All the words said are not her own, comments from observers are still not her own. We can never know what was truly in her heart, though maybe her poems are a good clue, being so direct and so melancholy. I wonder, were her manipulative ways a character trait or just a way of getting even with Rossetti. Why was she so miserable and what could have stopped that? I honestly can’t imagine her ever being perfectly happy. I think of her often, and yet she is still mysterious to me. Maybe one night, in a dream, I will meet her and find out all that I was curious about.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Portrait of Elizabeth Siddal, c. 1860

And for the end, here is one of her poems which I love:

Worn Out

Thy strong arms are around me, love

My head is on thy breast;

Low words of comfort come from thee

Yet my soul has no rest.

For I am but a startled thing

Nor can I ever be

Aught save a bird whose broken wing

Must fly away from thee.

I cannot give to thee the love

I gave so long ago,

The love that turned and struck me down

Amid the blinding snow.

I can but give a failing heart

And weary eyes of pain,

A faded mouth that cannot smile

And may not laugh again.

Yet keep thine arms around me, love,

Until I fall to sleep;

Then leave me, saying no goodbye

Lest I might wake, and weep.