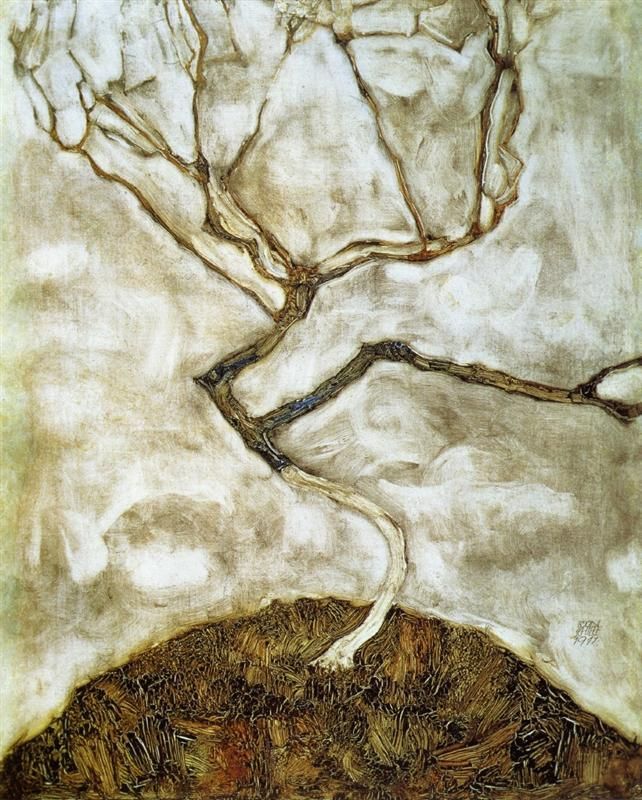

This June I enjoyed reading the poetry of the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, especially the poems from his poetry collections “Book of Poems”, “Suites” and “Poem of the Cante Jondo”. Many poems and many verses touched me and fired my imagination, but these days his poem “Elegy” from the “Book of Poems” lingers in my mind; the image of a life unlived, wasted, missed out on, an image of a love unfulfilled, passions and kisses not tasted, an image of loneliness, of longing for all that could have been, are all really powerful to me at this stage in life. I feel almost on a crossroad. The verses in bold are my particular favourites… The image of a woman watching people passing by, listening to the rain fall on the bitterness of old provincial streets, saddness in her eyes and in her soul, sweet serenade never reaching her, is very touching to me.

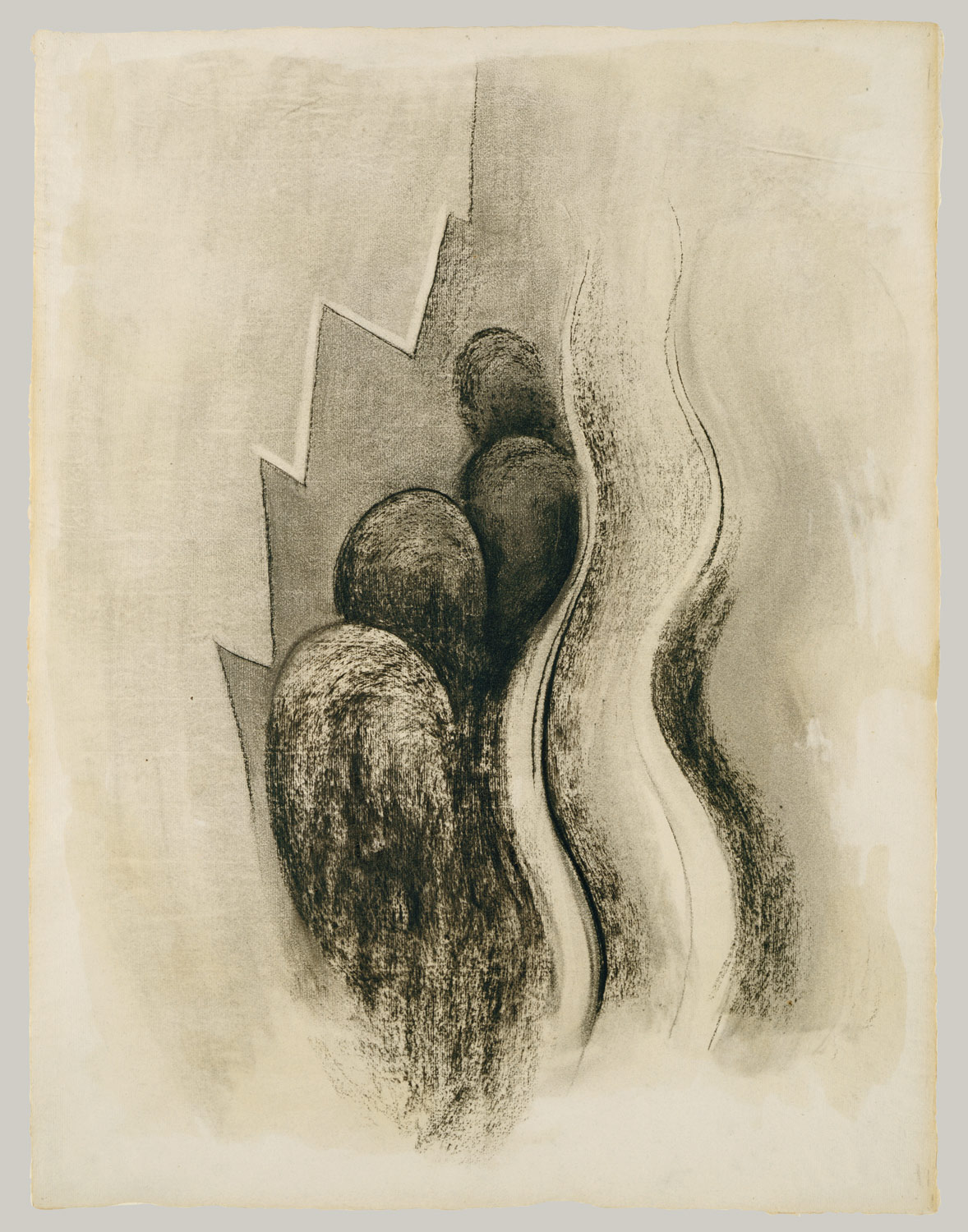

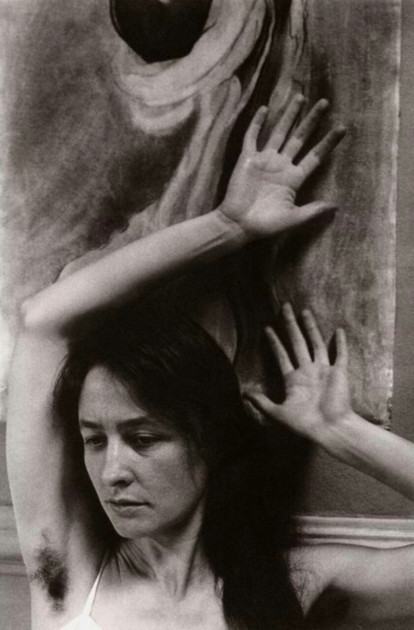

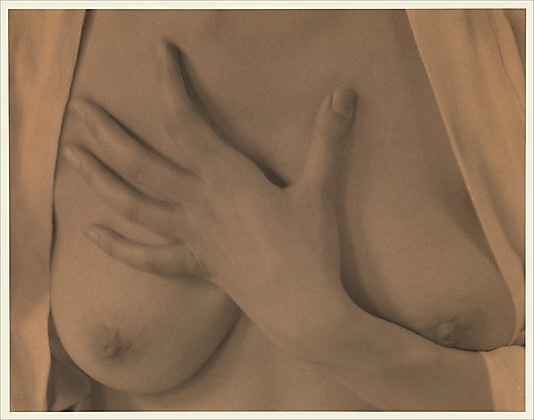

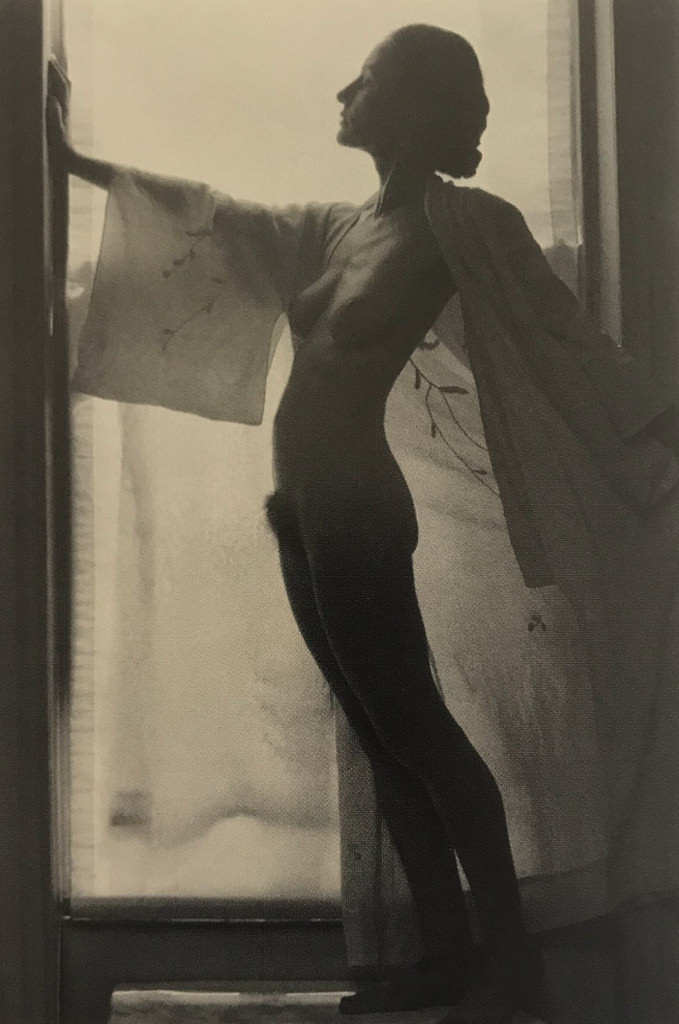

Photograph by Laura Makabresku

Photograph by Laura Makabresku

Elegy

Like a censer filled with desires,

you pass through clear evening,

flesh dark as spent spikenard;

your face pure sex.

On your mouth, dead chastity’s

melancholy; in your womb’s

Dionysian* chalice the spider weaves a barren veil

to hide flesh spurned by living roses,

the fruit of kisses.

In your white hands

the twist of lost illusions,

and on your soul a passion

hungry for kisses of fire,

and your mother-love dreaming distant

pictures of cradles in calm places,

lips spinning azure lullabies.

Like Ceres,* you’d offer golden corn

to have sleeping love touch your body;

to have another Milky Way

flow from your virgin breasts.

You’ll wither like the magnolia.

No kisses burnt on your thighs,

no fingers in your hair,

playing it like a harp.

Woman strong with ebony and spikenard,

breath white as lilies,

Venus of the Manila shawl tasting

of Málaga wine and guitars!

Black swan* on a lake of saeta

lotuses, waves of orange

and spray of red carnations scenting

the withered nests beneath its wings.

Andalusian martyr, left barren.

Your kisses should have been beneath a vine,

filled with night’s silence,

stagnant water’s cloudy rhythm.

But below your eyes circles start,

and your black hair turns silver.

Your breasts ease, spreading their scent

and your splendid shoulders start to stoop.

Slender woman, meant for motherhood, burning!

Virgin of sorrows;

forever hopeless heart

nailed by every star of the deep sky.

You’re the mirror of an Andalusia

suffering and stifling great passions,

passions swaying to fans

and mantillas at throats

shivering with blood, with snow,

red scratch-marks of gazing eyes on them.

Like Inés,* Cecilia,* and sweet Clara,*

you go through autumn mists, a virgin,

a bacchante who’d have danced

in garlands of green shoots and vine.

The great sadness floating in your eyes

tells us your broken, shattered life,

the monotony of your bare world,

at your window watching people pass,

hearing rain fall on the bitterness

of the old provincial streets;

far away, a troubled clash of bells.

But you listened to the air’s accents in vain.

The sweet serenade never reached you.

Behind your windows still you look and yearn.

The sadness that will flood your soul

when your wasted breast discovers

the passion of a girl new to love.

Your body will be buried

untouched by emotion.

A dawn song will spread

across the dark earth.

Two blood-red carnations will spring from your eyes,

and from your breasts, snow-white roses.

But your great sadness will join the stars,

a new star to wound and outshine the skies.

(December 1918, Granada)