“The image in the mirror may in some sense be a guarantee of identity and of wholeness. The root of narcissism lies in anxiety, and the fear of fragmentation, which may be assuaged by the sight of the reflection. (…) Venice always associated itself with the Virgin. But of course the image in the mirror is a false self; it is hard, abstract and elusive. It has been said that the Venetians are always aware of the image of themselves. They were once masters of the display and the masquerade. They were always acting.”

(Peter Ackroyd, Venice: Pure City)

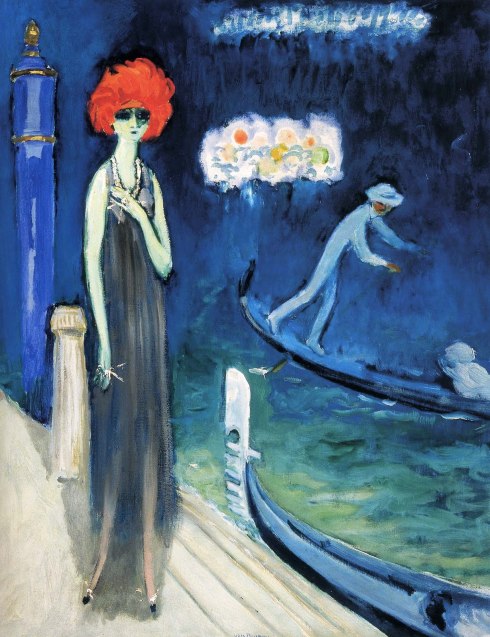

Kees Van Dongen, La Casati, 1918

Kees Van Dongen, La Casati, 1918

Dutch Fauvist painter Kees van Dongen once famously exclaimed that “painting was the most beautiful of all lies”, and it seems very fitting then to continue with his notion of painting being a lie and write about this beautiful portrait called “La Casati” from 1918. As the title suggests, the portrait shows the rich Italian heiress Luisa Casati who lived a life rich with adventures, scandals, depts, eccentricities and – art. Not that she was an artist, but she lived her life as if it were a work of art and, as wondrous a work of art as her life indeed was, it needed to be captured in paintings and photographs. Not only did Casati commision her portraits, but also many artists, painters and poets were flying around her as moths around a candle, drawn irresistibly to her legendary persona and intense individualism. Casati’s face, even in photographs, is a kind of dramatic face that one doesn’t forget too soon and I guess, in that regard, van Dongen’s portrait is realistic. Apart from the face perhaps, the portrait isn’t realistic at all, the figures are in fact very stylised and the colours are nonmimetic, far too intense and vibrant, though typical for Kees van Dongen’s Fauvist style. Still, even on a deeper layer it is ‘realistic’ because Luisa Casati’s extravagant persona and the nocturnal, fantasy city of Venice have a lot in common. Casati lived in Venice, from 1910 to 1920, at the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, on Grand Canal in Venice.

Even when she left the city, the city stayed inside of her because the two, Luisa and Venice, are as two sides of the same coin in terms of character; both posess the watery fluidity and bluntly refuse to be defined or define themselves, both are eccentric, self-obsessed narcissists with a fetish for deception and self-deception through lies and masquerade, anxiously putting on false facades, as is indeed typical for Venetian architecture, and layers and layers of rouge, red lipstick, mascara, feather boas, jewels and feathers, so that the final facade is so rich with layers which are impossible to peel off and get to the core. Luisa, like the waters and canals of Venice, is capricious and changeable. Garish red hair, large black eyes like bottomless abysses, unhealthy absinth-greenish complexion, thin and elongated figure, midnight blue formless, fluid gown. The scene at once nocturnal and Venetian, and yet out of time and place. Nothing about it seems realistic or accurate, and Kees van Dongen for one never strived to capture anything realistically, if painting is lying, then he lied beautifully. He would always put a special emphasis on the woman’s figure, and he would exaggerate it, elongate it purposefully, and the clients loved it.

Here is something from Peter Ackroyd’s book “Venice: Pure City” which I found particularly striking:

“But of course water is the life and breath of Venice’s being in quite another sense. Venice is like a hydropic body filled with water, where each part is penetrated by another. Water is the sole means of public transport. It is a miracle of fluid life. Everything in Venice is to be seen in relation to its watery form. The water enters the life of the people. They are “fluid”; they seem to resist clarity and precision. (…) In myth and folklore water has always been associated with eyes, and with the healing of eyes. Is it any wonder, then, that Venice is the most visually seductive of all the cities of the world?

The endless presence of water also breeds anxiety. Water is unsettling. You must be more alert and watchful in your perambulations. Everything shifts. There is a sense of otherness. The often black or viscous dark green water looks cold. It cannot be drunk. It is shapeless. It has depth but no mass. (…) But if water is the image of the unconscious life, it thereby harbours strange visions and desires. The close affiliation of Venice and water encourages sexual desire; it has been said to loosen the muscles, by human imitation of its flow, and to enervate the blood. Yet Venice reflects upon its own reflection in the water. It has been locked in that deep gaze for many centuries. So there has been a continuing association between Venice and the mirror.

(…) The image in the mirror may in some sense be a guarantee of identity and of wholeness. The root of narcissism lies in anxiety, and the fear of fragmentation, which may be assuaged by the sight of the reflection. The Virgin Mary, in the Book of Wisdom, is lauded as “a spotless mirror of God”; Venice always associated itself with the Virgin. But of course the image in the mirror is a false self; it is hard, abstract and elusive. It has been said that the Venetians are always aware of the image of themselves. They were once masters of the display and the masquerade. They were always acting. (…) It is a place of doubleness, and perhaps therefore of duplicity and double standards. (…) The reflection is delightful because it seems to be as substantial and as lively as that which is reflected. When you look down upon the water, Venice seems to have no foundations except for reflections. Only its reflections are visible. Venice and Venice’s image are inseparable. In truth there are two cities, which exist only in the act of being seen.”

Edmund Dulac, The Carnival, St Marks, Venice, n.d.

The blueness is absolutely intoxicating to me at the moment and I crave it the same way Elizabeth Siddal craved laudanum; in the blue waters of John Singer Sargent’s watercolours of Venice, in Klimt’s blue dress of Emilie Floge, in mosaics of Galla Placidia, in blue vases of Odilon Redon, in the blueness of Persian ceramics and interiors, blue of Edmund Dulac’s nocturnal Oriental fairy tale scenes, in Claude Monet’s blue waters beneath water lilies, and now, as I am gazing at this portrait by Kees van Dongen, I feel the blueness and the mystery seeping out of the painting and colouring my soul. I can feel the water, its depth and mystery, its scent, its constant movement, its secrecy. Everything in the painting is bathed in blueness; the background, the waters, the gondola and the gondolier, and even Luisa is dressed in a dress of midnight blue. There is so much intense blueness that it feels not as merely a nocturnal scene, but as a fantasy scene. Luisa is sailing the waters and threading the paths of her dreams.