“Hisako nodded teary-eyed and started playing that part over from the beginning. A melody flowed from the strings like the soft weeping of a homesick gypsy.”

(“The Uncharted Road” by Sakunosuke Oda)

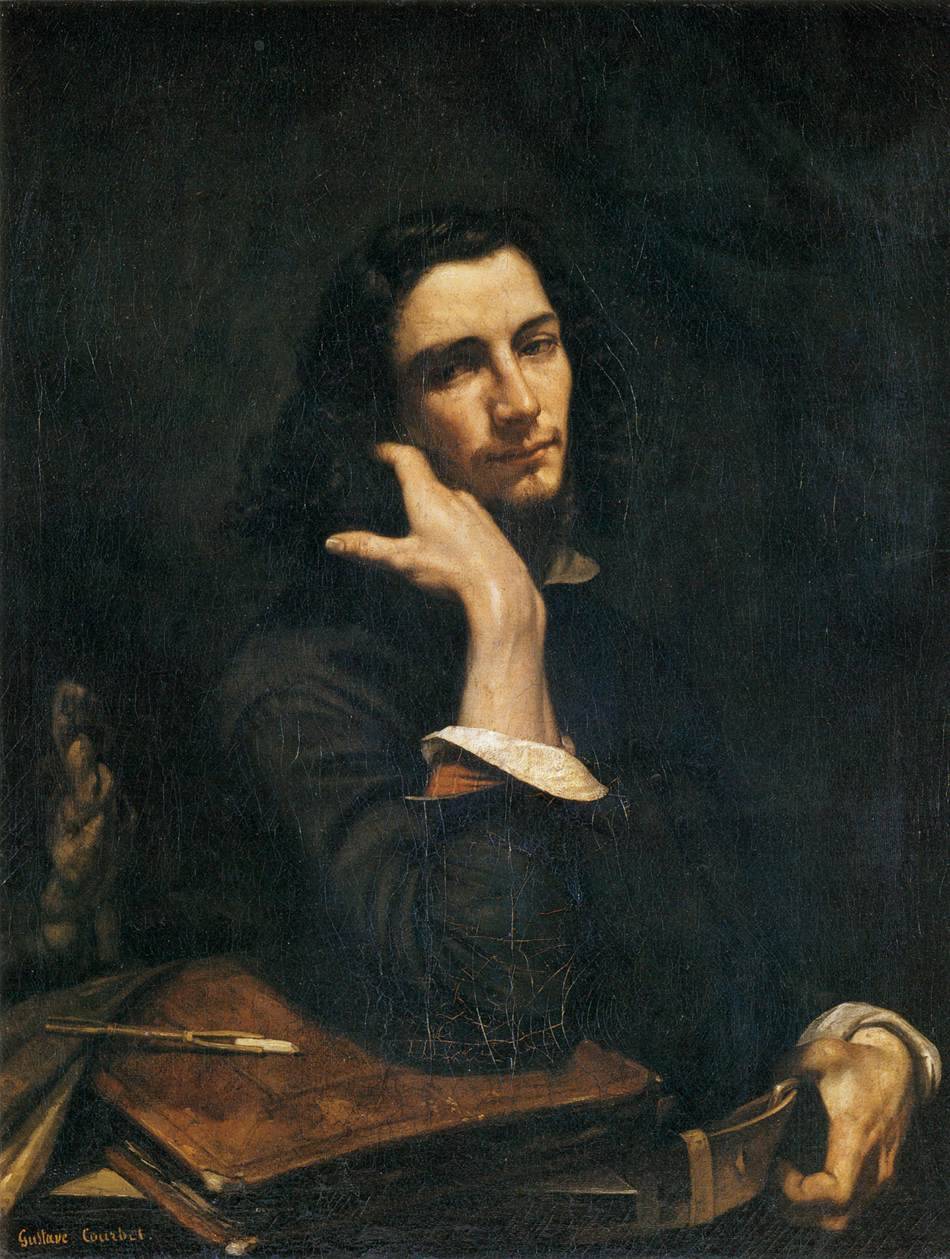

Berthe Morisot, Julie Playing a Violin, 1893

Berthe Morisot, Julie Playing a Violin, 1893

Once again I have had the pleasure of reading the freshly translated short stories by various authors in the book “Gensen: Selected Stories in Modern Japanese Literature” published last summer and translated by J.D.Wisgo. I have already written about his translations of works of Fumiko Hayashi, “Downfall and Other Stories” and “Days and Nights“, which I have enjoyed tremendously and also Masao Yamakawa’s “The Summer of Strangers“, which have both left a profound impact on me. If you enjoy short stories, if you are curious to discover new, perhaps not so popular writers, and especially if you have a passion for Japanese literature, then I am sure you will enjoy this little selection of short stories as much as I have.

This collection of short stories includes five stories all by different authors; “The Uncharted Road” by Sakunosuke Oda, “The Dream Egg” by Oshio Toyoshima, “Musical Clock” by Murou Saisei, “Space Prisoner Number One” by Juza Unno, and “The Mysterious Telescope” by Kyusaku Yumeno. This is a sampling of sorts, a delicious box of different flavoured chocolates, where each story comes with a different flavour, something for everyone. As the translator noted in the introduction, the word “gensen” means “specially selected”. All of these authors were completely new to me, and I am guessing will be to most of you as well, and that is why I think it was particularly lovely and useful that before each story there was a brief introduction to the author, his life and the themes of his literary work. Also, the first half of the book contains these short stories in English while the second part of the book has these same stories in parallel English/Japanese which would be very useful, I believe, for anyone learning or trying to learn Japanese.

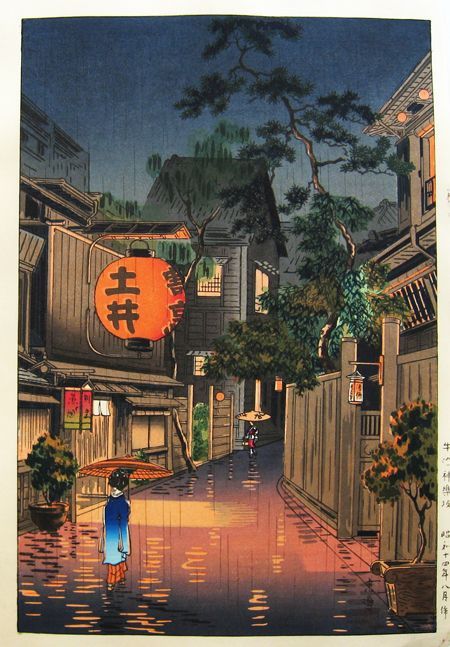

The stories were all different in style and in themes, and I was most surprised with the story “The Dream Egg” because of its Indian theme and setting. Whilst reading it I had images of Warwick Goble and Edmund Dulac floating in my mind. My favourite story, if I had to chose one, would have to be “The Uncharted Road” by Sakunosuke Oda (1913-1947), an author born in Osaka who primarily wrote novels, essays, and radio dramas. Interestingly, Oda was a close friend with Osamu Dazai whose famous novel “No Longer Human” I have enjoyed rereading these past few weeks. This sort of felt like a continuation of the sorts and I was especially intrigued to read a short story written by an author whose work was banned at times, as the brief introduction states. The short story is about a nine year old girl called Hisako and her father who is a strict violin teacher and who is forcing her to play day and night until she gets it right. Violin is one of my favourite instruments and it instantly made me think of this painting by Berthe Morisot, a portrait of her daughter playing violin. The mood of the story was so well conjured through words; Hisako’s suffering, her persistance and final success in a way, her father who “acted like a lunac whenever it came to the violin”, truly he seems like the most horrible music teacher in the world and reading the story I really felt sympathies for poor Hisako. Here is a short passage from the story about her playing:

“Hisako wanted to burst out crying. Yet perhaps due to her inborn, strong-minded spirit, she held back the tears. However, for some reason a terrible coldness dwelled in Hisako’s

eyes, and even her father Shonosuke could feel a chill from that light in her eyes. Those almond-shaped eyes were like the eyes of a mask, filled with an imposing, pale light that spoke of emptiness. Even if you tried to describe those mysterious eyes with everyday words such as “clever”, “unyielding”, or “an arrogance beyond her years,” there was something hard to put your finger on. But as she played the Bach fugue over and over, as if possessed, her eyes began to grow red to the point of being painfully bloodshot. To make matters worse, as night deepened, countless mosquitoes mercilessly bit into Hisako’s arms, hands, and neck.

“Poor thing…”

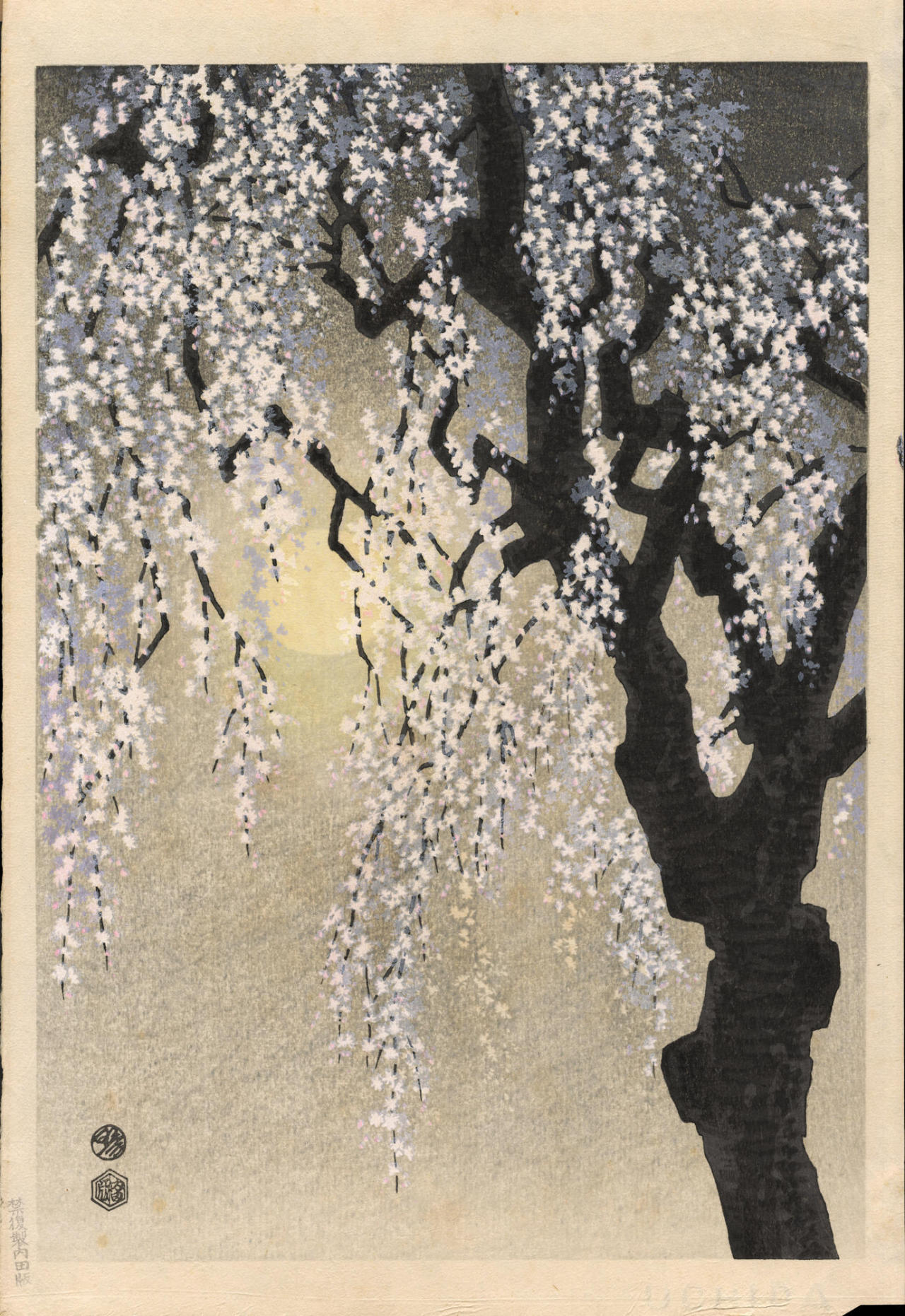

Kaburagi Kiyokata, Morning Dew — あさ露, 1903

All in all, if you love short stories and Japanese literature, I am sure you will enjoy these shorts stories. You can check out the translator’s word on his blog: Self Taught Japanese and Goodreads page.

This book is available here on Amazon.