In this post we’ll take a look at Charles Robert Leslie’s lovely Victorian era painting “A Lady Contemplating Suicide” from 1852, touch upon different types of suicides presented in Emile Durkheim’s book “Suicide: A Study in Sociology”, and also have a little overview of the representations of suicide in art, mostly nineteenth century examples.

Charles Robert Leslie, A Lady Contemplating Suicide (Juliet from William Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’, Act IV, sc. 3), 1852

Charles Robert Leslie, A Lady Contemplating Suicide (Juliet from William Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’, Act IV, sc. 3), 1852

A solemn mood in a sombre interior. The light is falling on the pale face of a lovelorn young girl. Too young is the face upon which the misery of an impossible love had already left a trace. The girl, sitting on that chair, is a part of that interior only physically but in spirit she is elsewhere, deep in thoughts no other mortal could understand, or so she thinks. A vial in her hand and a distant gaze speak of an inner turmoil. All the drama of the scene is happening on her lovely countenance, the beauty of which had only been intensified by the wistful thoughts of doom and gloom. Juliet here brings to mind other ladies in contemplation such as the penitent Mary Magdalene by a candle in the paintings by Georges Le Tour, or some seventeenth century painting of a martyr. Victorian genre painter Charles Robert Leslie painted quite a few interesting historical and Shakespearean scenes but this depiction of Juliet contemplating suicide was the most interesting to me at the moment. The scene that Leslie decided to portray is Juliet’s monologue from the Act IV:

Without seeing the title of the painting, I wouldn’t have guessed that the painting shows Juliet but now, reading these words from the play, I do feel that the girl in the painting is indeed Juliet. Apart from the vial you can also see a dagger on the table, another visual hint to what the contemplating lady may be contemplating about. I also really love how the light falls on her; the way her brown hair turns to coppery shades in the light and how the iridescent glow of the red satin dress is also revelaed by the light.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Lucretia, 1627

In one of my previous posts I had written about Manet’s painting “The Suicide” and Emile Durkheim’s book “Suicide: A Study in Sociology” published in 1897. Durkheim, being a sociologist, was naturally curious to see whether a correlation could be made between an individual act of suicide with society as a whole, and he established four types of suicides. But before Durkheim, suicides were viewed through a psychological lense, as an act caused by the individual’s temperament and mental state, not as something connected to society. In the beginning of his book, Durkheim touched upon the classification of the four types of suicides described by two nineteenth century French psychiatrists, quoting the book:

“The four following types, however, probably include the most important varieties. The essential elements of the classification are borrowed from Jousset and Moreau de Tours.

1. Maniacal suicide.—This is due to hallucinations or delirious conceptions. The patient kills himself to escape from an imaginary danger or disgrace, or to obey a mysterious order from on high, etc. But the motives of such suicide and its manner of evolution reflect the general characteristics of the disease from which it derives—namely, mania. The quality characteristic of this condition is its extreme mobility. The most varied and even conflicting ideas and feelings succeed each other with intense rapidity in the maniac’s consciousness. It is a constant whirlwind. One state of mind is instantly replaced by another. Such, too, are the motives of maniacal suicide; they appear, disappear, or change with amazing speed. The hallucination or delirium which suggests suicide suddenly occurs; the attempt follows; then instantly the scene changes, and if the attempt fails it is not resumed, at least, for the moment. If it is later repeated it will be for another motive.

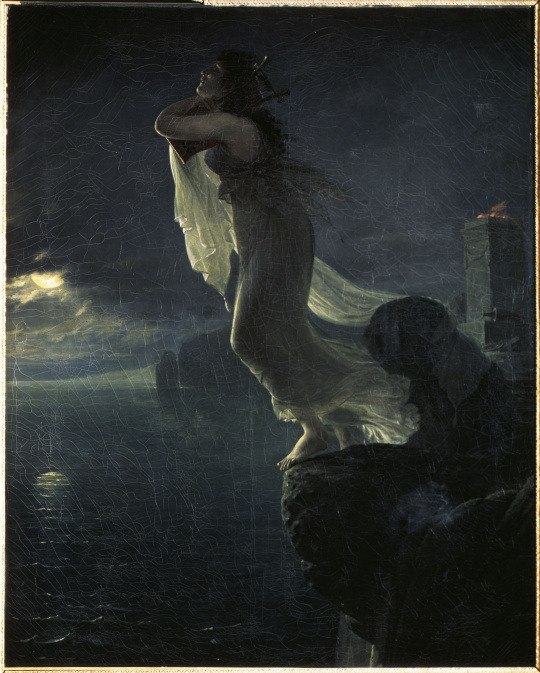

Antoine Jean Gros, Sapho à Leucate, 1801

Jean Victor Schnetz, Sapho se laissant tomber dans la mer, c 1820s

“2. Melancholy suicide.—This is connected with a general state of extreme depression and exaggerated sadness, causing the patient no longer to realize sanely the bonds which connect him with people and things about him. Pleasures no longer attract; he sees everything as through a dark cloud. Life seems to him boring or painful. As these feelings are chronic, so are the ideas of suicide; they are very fixed and their broad determining motives are always essentially the same.

A young girl, daughter of healthy parents, having spent her childhood in the country, has to leave at about the age of fourteen, to finish her education. From that moment she contracts an extreme disgust, a definite desire for solitude and soon an invincible desire to die. “She is motionless for hours, her eyes on the ground, her breast laboring, like someone fearing a threatening occurrence. Firmly resolved to throw herself into the river, she seeks the remotest places to prevent any rescue.”

However, as she finally realizes that the act she contemplates is a crime she temporarily renounces it. But after a year the inclination to suicide returns more forcefully and attempts recur in quick succession. Hallucinations and delirious thoughts often associate themselves with this general despair and lead directly to suicide. (…) The fears by which the patient is haunted, his self-reproaches, the grief he feels are always the same. If then this sort of suicide is determined like its predecessor by imaginary reasons, it is distinct by its chronic character. And it is very tenacious. Patients of this category prepare their means of self-destruction calmly; in the pursuit of their purpose they even display incredible persistence and, at times, cleverness.”

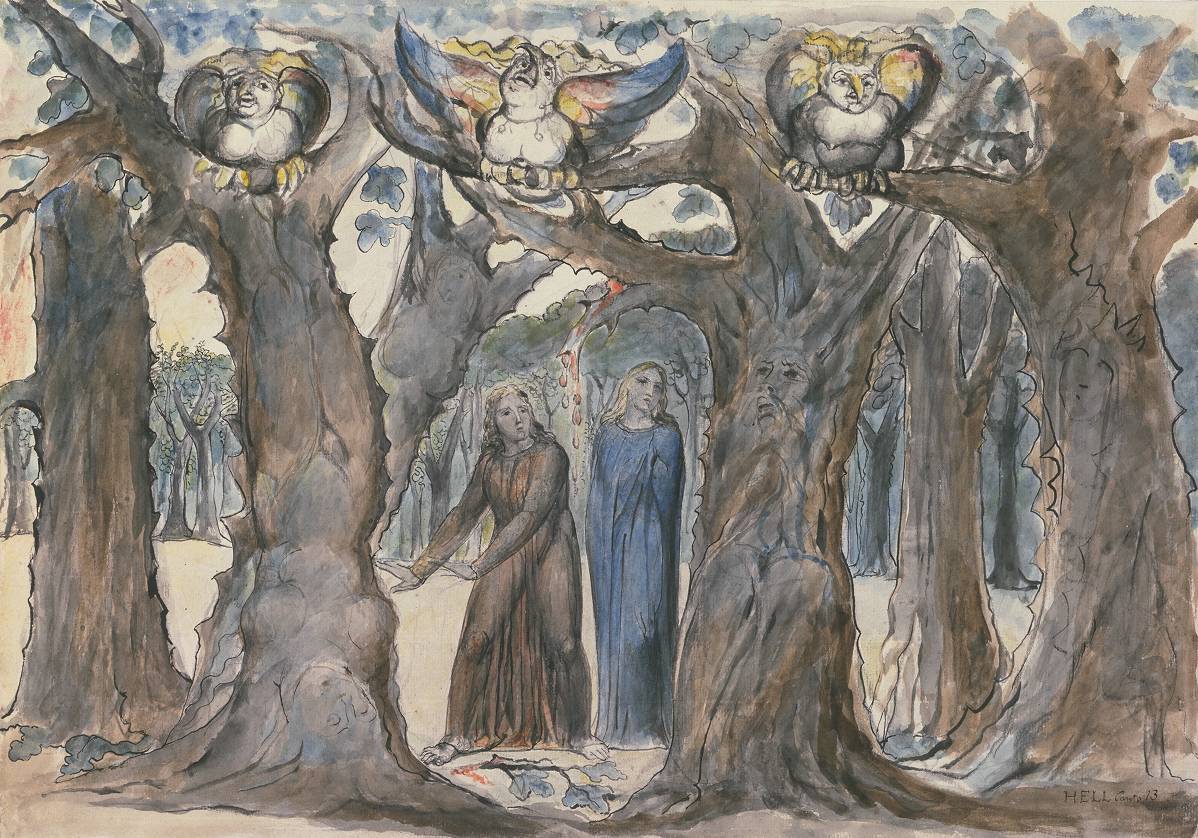

William Blake, The Wood of the Self-Murderers – The Harpies and the Suicides, 1824-27, pencil, ink and watercolour on paper

“3. Obsessive suicide.—In this case, suicide is caused by no motive, real or imaginary, but solely by the fixed idea of death which, without clear reason, has taken complete possession of the patient’s mind. He is obsessed by the desire to kill himself, though he perfectly knows he has no reasonable motive for doing so. It is an instinctive need beyond the control of reflection and reasoning, like the needs to steal, to kill, to commit arson, supposed to constitute other varieties of monomania. As the patient realizes the absurdity of his wish he tries at first to resist it. But throughout this resistance he is sad, depressed, with a constantly increasing anxiety oppressing the pit of his stomach. Hence, this sort of suicide has sometimes been called anxiety-suicide.

Here is the confession once made by a patient to Brierre de Boismont, which perfectly describes the condition: “I am employed in a business house. I perform my regular duties satisfactorily but like an automaton, and when spoken to, the words sound to me as though echoing in a void. My greatest torment is the thought of suicide, from which I am never free. I have been the victim of this impulse for a year; at first it was insignificant; then for about the last two months it has pursued me everywhere, yet I have no reason to kill myself. . . . My health is good; no one in my family has been similarly afflicted; I have had no financial losses, my income is adequate and permits me the pleasures of people of my age.” But as soon as the patient has decided to give up the struggle and to kill himself, anxiety ceases and calm returns. If the attempt fails it is sometimes sufficient, though unsuccessful, to quench temporarily the morbid desire.”

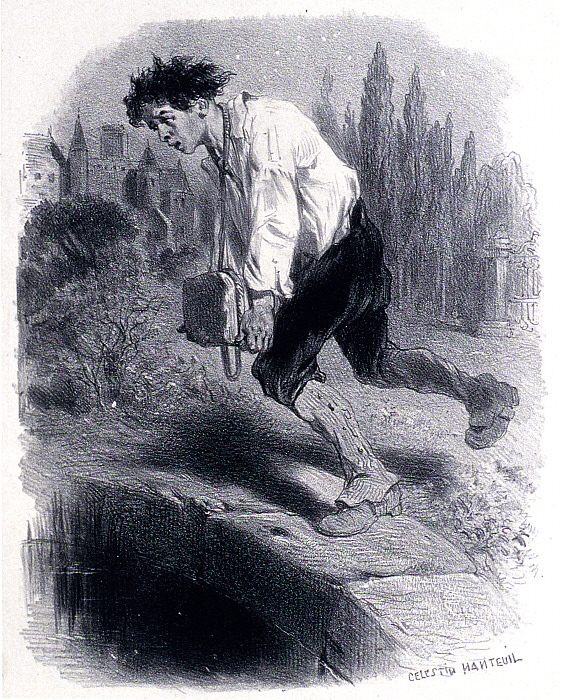

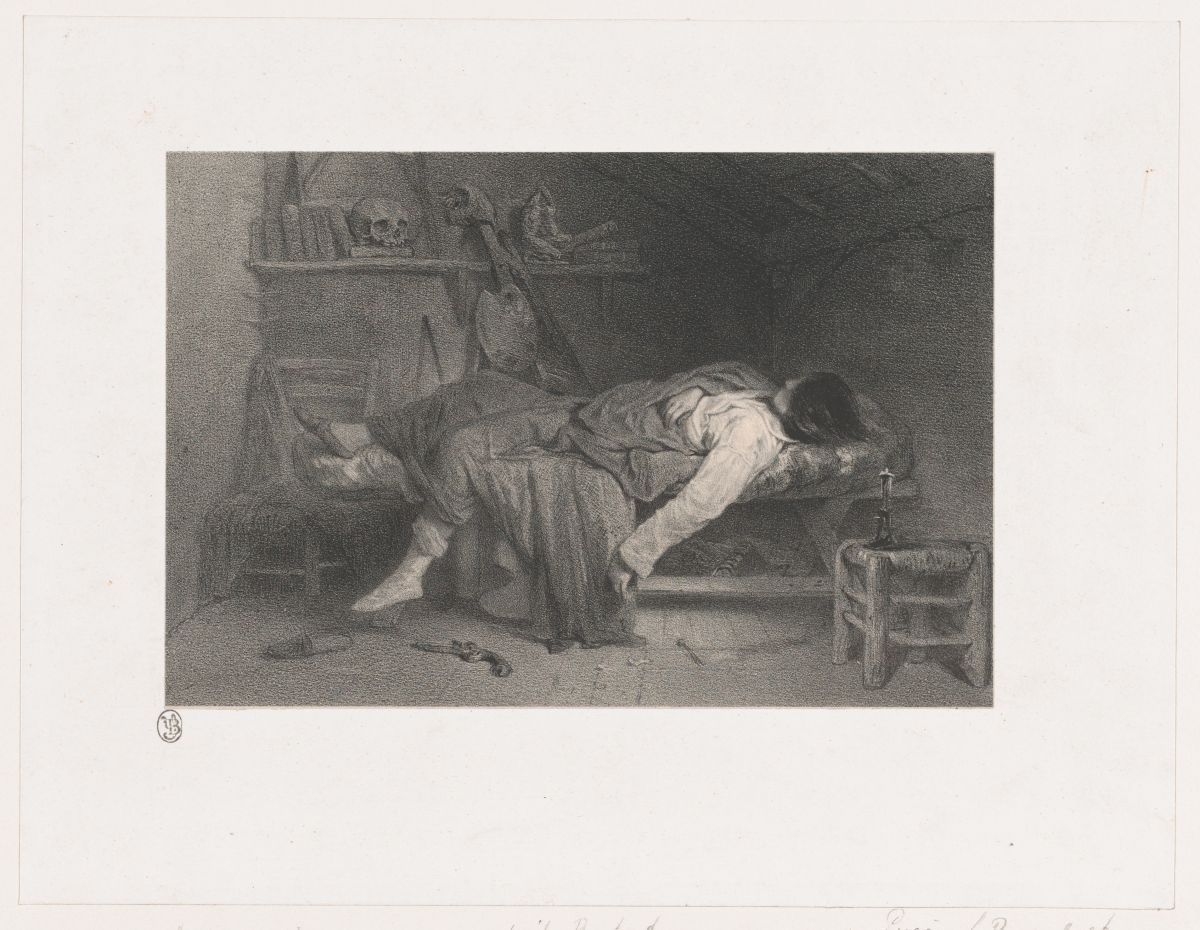

Célestin François Nanteuil, Suicide, c 1830s, litograph

“4. Impulsive or automatic suicide. – It is as unmotivated as the preceding; it has no cause either in reality or the patient’s imagination. Only, instead of being produced by a fixed idea obsessing the mind for a shorter or longer period and only gradually affecting the will, it results from an abrupt and immediately irresistible impulse. In the twinkling of an eye it appears in full force and excites the act, or at least its beginning. This abruptness recalls what has been mentioned above in connection with mania; only the maniacal suicide has always some reason, however irrational. It is connected with the patient’s delirious conceptions. Here on the contrary the suicidal tendency appears and is effective in truly automatic fashion, not preceded by any intellectual antecedent. The sight of a knife, a walk by the edge of a precipice, etc. engender the suicidal idea instantaneously and its execution follows so swiftly that patients often have no idea of what has taken place.”

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, The Suicide, 1836

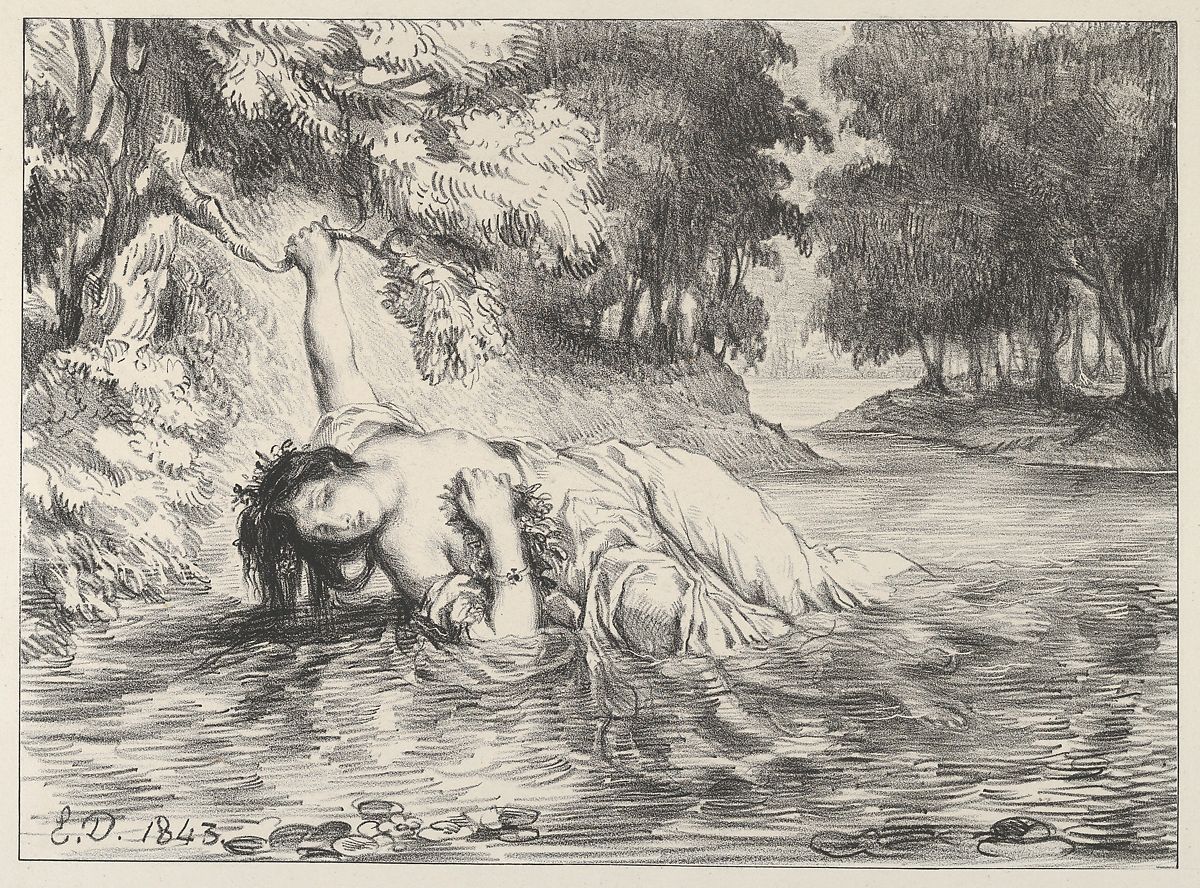

Eugene Delacroix, The Death of Ophelia, 1843

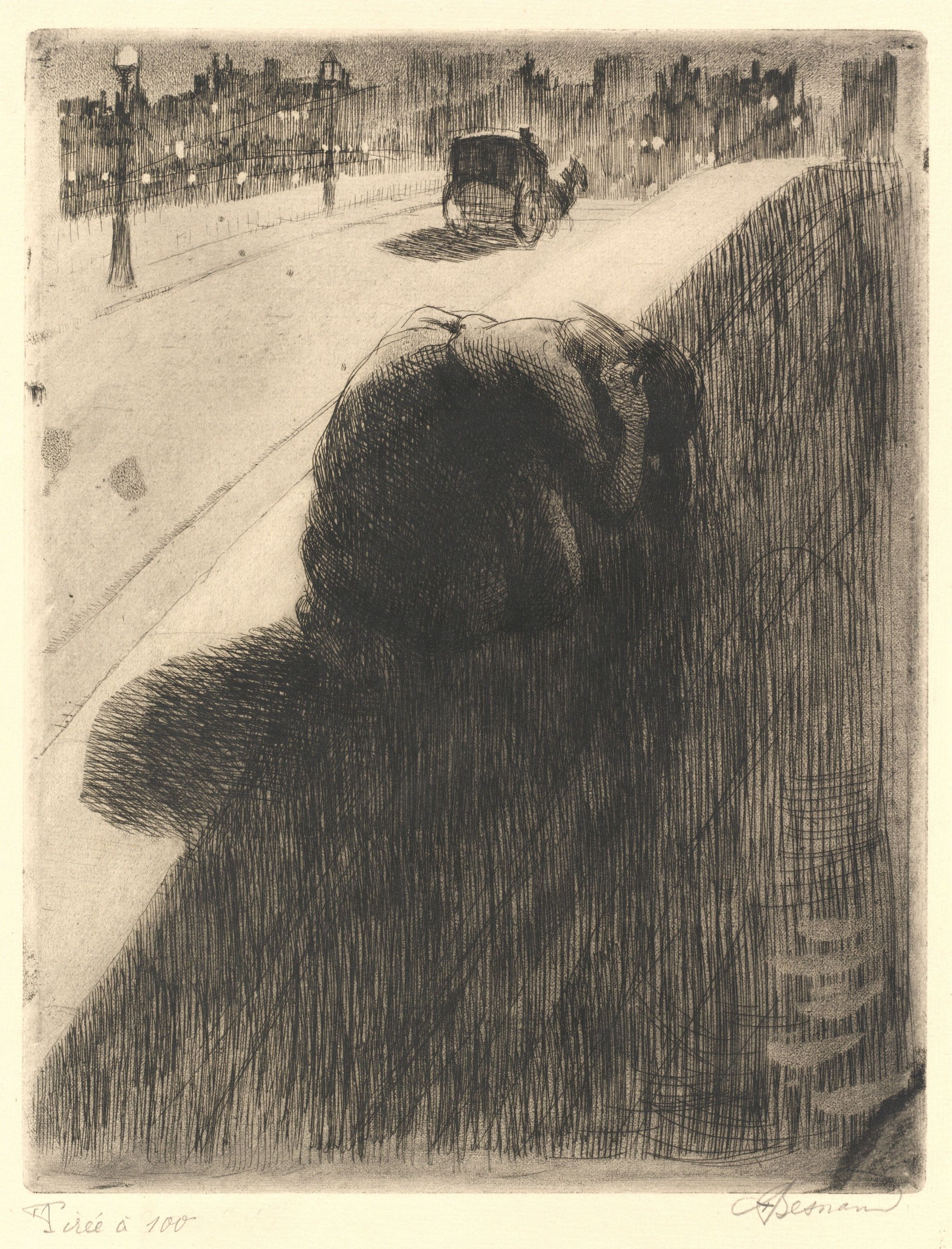

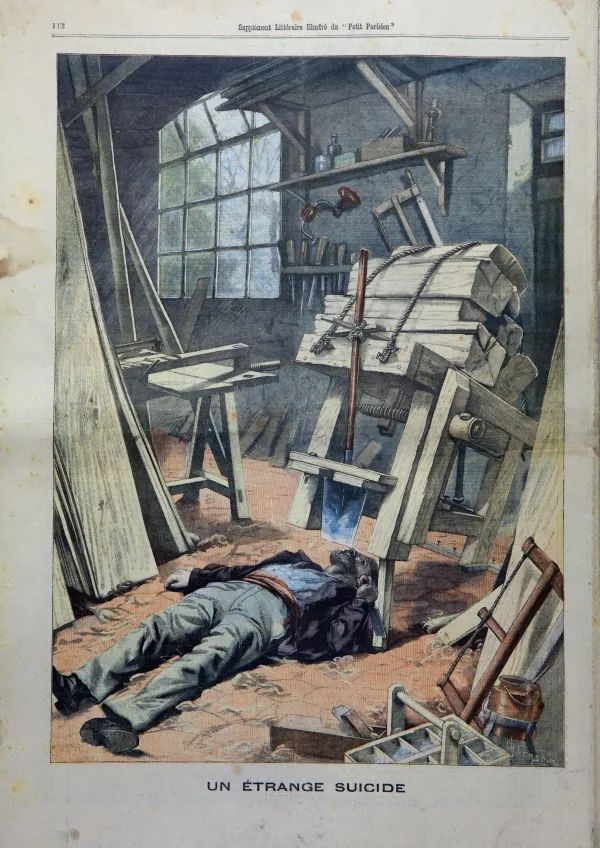

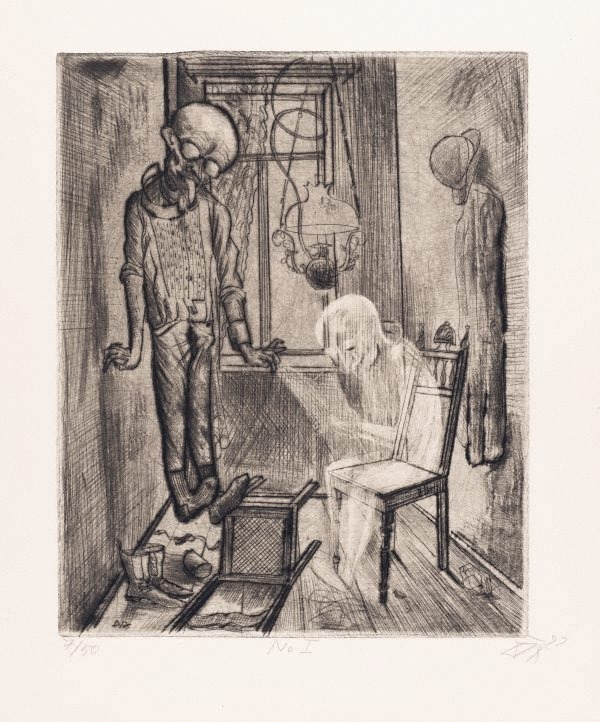

I hope you have enjoyed the excerpts from Durkheim’s book as much as I have. Suicide is, more often than not, a highly romanticised idea in art and literature; it is a relief from the misery of this world, an escape from the burdens of reality’s disappointment. In Romantic poetry death is connected to the state of sleep and dream, it is mysterious and otherworldy, it’s full of sweet promises. Looking at the selection of paintings that depict suicides it is easy to see they fall into two distinct categories; some are very romantic and some are … not. If we look at the painting and drawing of the lovelorn Greek poetess Sappho jumping off the cliff, Ophelia drowning and merging with the green river and all the flowers, becoming one with nature, returning to the original source of all things, or the pale body of a redhead poet Chatterton stretched on the bed, all so young and so beautiful, escaping reality that simply couldn’t meet their demands, a wave of Romanticism flushes over us, we sigh, we daydream, we curse the fate and the world that allowed that to happen. But when we look at the other examples, such as the paintings of Manet, Decamps, Leroux, and Otto Dix, we are met with a more cold, distant and realistic portrayal of suicide. In three out of four paintings there is a gun or still in the man’s hands; even the weapon of choice itself is a cold and modern, which brings to mind another sociologist, Max Weber, and his theory about the rationalisation of the world. It’s inexplicable, but jumping off the cliff into the sea, or drowning, or drinking too much laudanum, all seem like very romantic ways to die, but a gun, it’s something rational and quick. Still, it was a preferred method for Goethe’s hero Werther, so there is a contradiction here. I will not go into detail about each of these paintings, and I hope you enjoy them, if I can use the word ‘enjoy’ because the topic is suicide in art, but it is something that is fascinating to me.

Eugene Leroux, The Suicide, 1846

John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1852

I end this post with lyrics from the Manic Street Preacher’s song “Suicide is Painless”:

Visions of the things to be

The pains that are withheld for me

I realize and I can see

It brings on many changes

I can take or leave it if I please

That game of life is hard to play

The losing card of some delay

So this is all I have to say

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

And you can do the same thing if you please…

Henry Wallis, The Death of Chatterton, 1856

Edouard Manet, The Suicide, 1877-81

Albert Besnard, The Suicide (Le Suicide), c. 1886

Suicide, April 5, 1903, French illustrated newspaper Le Petit Parisien

Otto Dix, The Suicide, 1922