“…does not someone who, like me,

Lives on among so many evils, profit

By dying?“

(Sophocles, Antigone)

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927), Antigone, no date

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927), Antigone, no date

When, back in high school, I first read a few passages from the Greek tragedy “Antigone”, written by Sophocles in 441 BC, I wasn’t particularly interested in it, but now I decided to read the play again because the play’s central theme – the civil disobedience – is something that resonates strongly with today’s events. The strong and brave Antigone is a true heroine and reading the play filled me with a sense of direction and gave me encouragment.

Antigone, the play’s heroine and the main character, is the daughter of Oedipus and Jocasta, and the sister of Ismene, Polynices and Eteocles. An event that happens before the start of the play is the civil war of Thebes in which Antigone’s brothers Polynices and Eteocles fight on different sides. Antigone’s uncle Creon gives an order that Eteocles must have an honorable burial but Polynices must be left unburried in the battlefield and his dead body will be food for vultures, as a punishment for his rebellion. The play begins with a conversations between Antigone and Ismene; the brave Antigone who is led by justice wishes to give her brother a proper burial because she feels that is the right thing to do, but Ismene, who is a lawful and obedient daughter, dares not to do this, even though she knows in her heart it is the right thing. Ismene begs Antigone not to proceed with her plan because she knows how harsh the punishment will be when the King Creon finds out, but Antigone doesn’t listen to her sister and instead says:

ANTIGONE:

For me it’s noble to do

This thing, then die. With loving ties to him,

I’ll lie with him who is tied by love to me,

I will commit a holy crime, for I

Must please those down below for a longer time

Than those up here, since there I’ll lie forever.

Antigone and Ismene by Emil Teschendorff, Antigone and Ismene, n.d.

ISMENE: You have a heart that’s hot for what is chilling.

ANTIGONE: But I know I’m pleasing those I must please most.

In the painting by Emil Teschendorff above you can see the beautiful, blue-eyed and blonde Ismene trying to convince Antigone not to go out and bury her brother. What a visual contrast they make; Ismene is dressed in light clothes, she is bright and fair, and Antigone is dressed in a dark blue, with dark hair. Ismene is the good and proper daughter, and Antigone is the stubborn rebel and troublemaker. Their personalities are indeed as different as day is to night, but this ‘light’ and positive representation of Ismene is very misleading because ‘obedience’ doesn’t equal ‘goodness’ or ‘justice’. Being obedient doesn’t mean doing the right thing, it means doing what you were told to do without questioning it.

Nikiforos Lytras, Antigone in front of the dead Polynices, 1865

As you can see, there are many interesting representations of Antigone in art, especially the scene where Antigone finds the body of her dead brother and gives him a proper burial. Greek painter, appropriately, Nikiforos Lytra places the scene at a rocky beach. Behind Antigone the dark sea and the moody sky meet. She gazes in disbelief at her brother’s corpse. In Benjamin-Constant’s version of the scene the Antigone is dressed in a white gown and while she is performing the ritual two guards behind here have just caught her in the act.

Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, Antigone au chevet de Polynice, 1868

In the watercolour by Lenepveu the naked body of Polynices is stretches under Antigone’s feet while she is sprinkling dust all over him and perfroming the ritual. Their poses and the way the red cloth is carefully placed to cover Polynices’s private part makes the scene seem staged and not as mysterious or as spontaneous as the previous paintings. My favourite is the version by the Pre-Raphaelite painter of Greek origin Marie Spartali Stillman; the landscape behind Antigone is a moody one and the crows add to the ominous appeal, both sisters are next to their brother’s body and Ismene is holding Antigone’s hand imploringly, desperately trying to prevent her from doing what she is about to do.

Jules Eugene Lenepveu (1819-1898), Antigone Gives Token Burial to the Body of Her Brother Polynices, c. 1835-1898, watercolor, pen and black ink over black chalk, on gray-green paper

Ismene with her moral lenience, her cowardice and lack of passion and integrity reminds me of a quote by Robert Anton Wilson which is very appropriate for our times: “The obedient always think about themselves as virtuous, rather than cowardly.” And this leads us to another moral dilemma which is at the centre of the play: obedience to what or whom? Obedience to civil laws made by men, or obedience to something higher; obedience to God or your own conscience? Which is more important? Ismene doesn’t want to create an inconvenience or disobey the civil law but Antigone doesn’t care about laws on earth because she knows that she must please the Gods first; her life on earth is brief but the life of her soul is eternal.

Isn’t it fascinating how when we are presented with something in retrospective, or in art, everything is perfectly clear to us; it is obvious that Antigone is a brave and principled heroine, that Ismene is weak and obedient, that Creon is a tyrannt. Everyone would agree that Antigone did the right thing, and yet, in real life, everything is twisted and upside-down; blind obedience, conformity and cowardice are celebrated as bravery, real bravery is portrayed as dangerous ignorance and even lunacy, not to mention that Truth and Logic have been the first victims of our tragedy; they died in Act One. If our situation was a Greek play it would be obvious who was on the right side, as history will inevitably show too. To end, here is a brilliant dialogue between the King Creon and Antigone where he questions her about what she has done and Antigone gives him a brilliant, intelligent, even a bit cheeky reply. Go, Antigone!:

KREON: You — answer briefly, not at length — did you know

It was proclaimed that no one should do this?

ANTIGONE I did. How could I not? It was very clear.

KREON And yet you dared to overstep the law?

ANTIGONE:

It was not Zeus who made that proclamation

To me; nor was it Justice, who resides

In the same house with the gods below the earth,

Who put in place for men such laws as yours.

Nor did I think your proclamation so strong

That you, a mortal, could overrule the laws

Of the gods, that are unwritten and unfailing.

For these laws live not now or yesterday

But always, and no one knows how long ago

They appeared. And therefore I did not intend

To pay the penalty among the gods

For being frightened of the will of a man.

I knew that I will die —how can I not? —

Even without your proclamation. But if

I die before my time, I count that as

My profit. For does not someone who, like me,

Lives on among so many evils, profit

By dying? So for me to happen on

This fate is in no way painful. But if

I let the son of my own mother lie

Dead and unburied, that would give me pain.

This gives me none. And now if you think my actions

Happen to be foolish, that’s close enough

To being charged as foolish by a fool.“

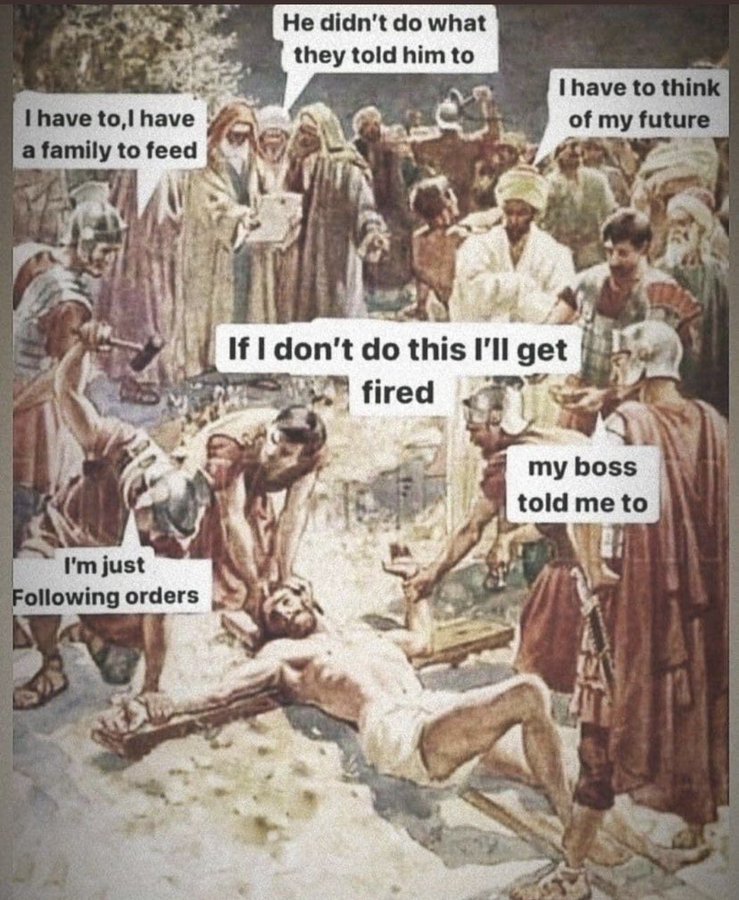

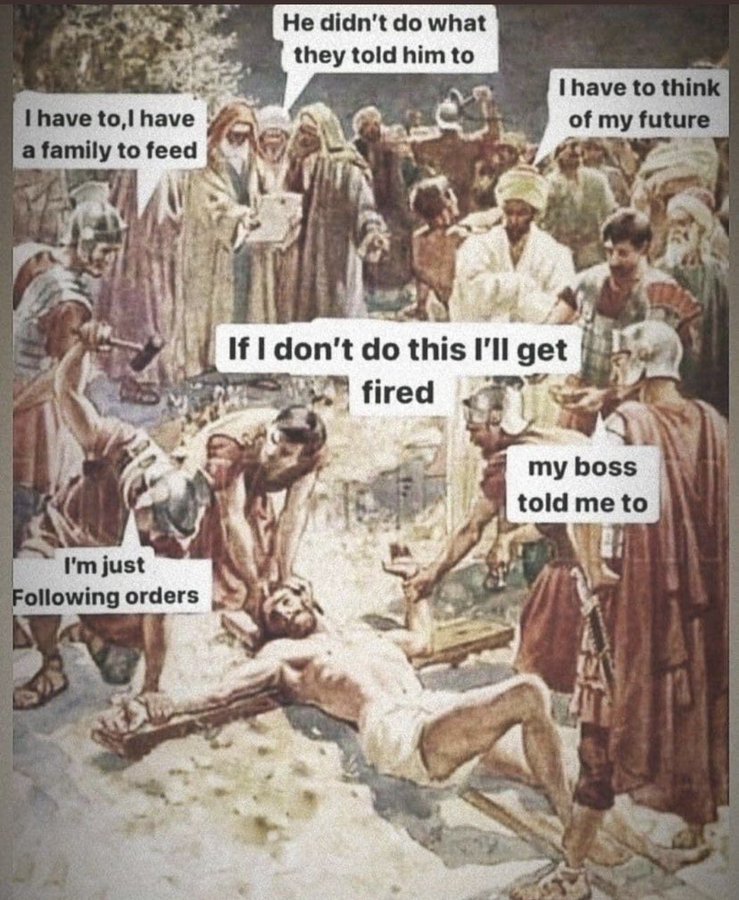

Oh and the guards in the play who told the King that they saw Antigone are the perfect examples of people who are “just doing their job”, which is something I am sick to my stomach of hearing. The picture above is something I found on The Stone Roses frontman Ian Brown’s Twitter, but I have seen it in other places and I don’t know who the original creator is.

Tags: abstract expressionism, Antigone, Antigone in front of the dead Polynices, art, art blog, brave, bravery, burial, civil disobedience, civil law vs god's law, defiance, Greek tragedy, Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, Jules Eugene Lenepveu, Marie Spartali Stillman, Nikiforos Lytras, Painting, Polynice, Pre-Raphaelites, Sophocles, tragedy, watercolour

Wassily Kandinsky, Riding Couple (Couple on Horseback), 1906-07

Wassily Kandinsky, Riding Couple (Couple on Horseback), 1906-07

The grounds of Gwydir Castle near to Llanrwst, County Conwy, in North Wales. Artist:

The grounds of Gwydir Castle near to Llanrwst, County Conwy, in North Wales. Artist: