“They who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.” (Edgar Allan Poe)

Berthe Morisot, Julie Daydreaming, 1894

Berthe Morisot, Julie Daydreaming, 1894

A portrait of a wistful round-faced girl in a loose white gown, with large heavy-lidded dreamy eyes, pouting and gazing in the distance, supporting her face with a delicate white hand; it’s Julie Manet, portrayed here in the sweet state of daydreams in the spring of her life, aged sixteen, by her mother Berthe Morisot.

I have been loving this portrait of Julie, it’s charming and subject of daydreams is very well known to me, but this is just one out of many portraits of Julie that Morisot has done. Julie was her mother’s treasure and her favourite motif to paint since the moment she was born on 14 November 1878, when Morisot was thirty-seven years old. Morisot comes from a wealthy family with good connections and this enabled her the freedom to pursue her artistic career. Another interesting thing is that her mother, Marie-Joséphine-Cornélie Thomas was the great-niece of the Rococo master Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Berthe had art flowing her veins.

Berthe Morisot, Julie with Her Nurse, 1880

Berthe Morisot, Julie with Her Nurse, 1880

Berte Morisot was part of the Impressionist circles, and married Eugene Manet, younger brother of Edouard Manet. Very early on, she had shown interest in painting children and made lots of portraits of her sisters with their children, so the arrival of little Julie enriched both her personal and artistic life, and she was known to have always tried mingling the two together, as explained by the poet Paul Valéry, her niece’s husband: “But Berthe Morisot singularity consisted in … living her painting and painting her life, as if this were for her a natural and necessary function, tied to her vital being, this exchange between observation and action, creative will and light … As a girl, wife, and mother, her sketches and paintings follow her destiny and accompany it very closely.”

When Morisot painted other children, those were just paintings, studies, paint-on-canvas, but with Julie it was more than that, it was a project, one we could rightfully call “Julie grows up” or “studies of Julie” because since the moment Julie was born to the moment Morisot herself died, in 1895, she painted from 125 to 150 paintings of her daughter. Degas had his ballerinas, Monet his water lilies and poplars, and Berthe had her little girl to paint. It’s interesting that Morisot never portrayed motherhood in a typical sentimental Victorian way with a dotting mother resembling Raphael’s Madonna and an angelic-looking child with rosy cheeks. She instead gave Julie her identity, even in the early portraits she emphasised her individuality and tended to concentrate on her inner life. This makes Julie real, we can follow her personality, her interests and even her clothes through the portraits. Also, Morisot didn’t hesitate to paint Julie with her nanny or wet nurse, showing her opinion that the maternal love isn’t necessarily of the physical nature, but artistic; she preferred painting over breastfeeding her baby girl.

Édouard Manet, Julie Manet sitting on a Watering Can, 1882

Édouard Manet, Julie Manet sitting on a Watering Can, 1882

As a lucky little girl and a daughter of two artists, Julie received a wonderful artistic upbringing. She was educated at home by her parents, and spent only a brief time at a local private school. Morisot, who saw her nieces Jeannie and Paule Gobillard as her own daughters, taught all three girls how to paint and draw, and also the history of art itself. Morisot took Julie to Louvre, analysed sculptures in parks with her and together they discussed the colour of shadows in nature; they are not grey as was presented in academic art. Morisot also started an alphabet book for Julie, called “Alphabet de Bibi” because “Bibi” was Julie’s nickname; each page included two letters accompanied by illustrations. (Unfortunately, I can’t find a picture of that online)

Still, Morisot wasn’t the only one to capture Julie growing up, other Impressionist did too, most notably Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Julie’s uncle Edouard Manet who made a cute depiction of a four year old Julie sitting on a watering can, wearing a blue dress and rusty-red bonnet. Julie’s childhood seems absolutely amazing, but her teenage years were not so bright. In 1892, her father passed away, and in 1895 her mother too; she was just sixteen years old and an orphan. The famous symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who died himself just four years later, became her guardian, and she was sent to live with her cousins.

Berthe Morisot, The Artist’s Daughter Julie with her Nanny, c. 1884.

Berthe Morisot, The Artist’s Daughter Julie with her Nanny, c. 1884.

Berthe Morisot, Young Girl with Doll, 1884

Berthe Morisot, Young Girl with Doll, 1884

Like all Impressionist, Bethe Morisot painted scenes that are pleasant to the eye and very popular to modern audience, but what appeals me the most about her art is the facture; in her oils it’s almost sketch-like, it’s alive, it breaths and takes on life of its own, her bold use of white, her brushstrokes of rich colour that look as if they are flowing like a vivacious river on the surface of the canvas, and her pastels have something poetic about them. Just look at the painting The Artist’s Daughter Julie with her Nanny above, look at those strong, wilful strokes of white and blue, that tickles my fancy! Or the white sketch-like strokes on Julie with Her Nurse.

It was Renoir who encouraged Morisot to experiment with her colour palette and free both the colour and brushwork. It may not come as a surprise that Julie loved her mother’s artworks, in fact the lovely painting of a girl clutching her doll was Julie’s favourite, and she had it hanged above her bed. Imagine waking up to this gorgeous scene, knowing that it was painter by your dearest mama.

Berthe Morisot, The Piano, 1889

Berthe Morisot, The Piano, 1889

Both Renoir and Morisot fancied portraying girl playing piano, and this is Morisot’s version of the motif, made in pastel. The girl painted in profile, playing piano and looking at the music sheet is Julie’s cousin Jeannie, while the eleven year old Julie is shown wearing a light blue dress and sporting a boyish hairstyle. She is here, but her thoughts are somewhere else, her head is leaned on her hand and she’s daydreaming… Oh, Julie, what occupies your mind?

Berthe Morisot, Portrait of Julie, 1889

Berthe Morisot, Portrait of Julie, 1889

And here is a beautiful pastel portrait of Julie, also aged eleven but looking more girly with soft curls framing her round face, and a pretty pink bow. There’s something so poetic about her face; her almond shaped eyes gaze at something we don’t see, her face is always tinged with melancholy, even in her photo. Playful strokes of white chalk across her face, her auburn hair ending in sketch-like way…

Berthe Morisot, Portrait of Julie Manet Holding a Book, 1889

Berthe Morisot, Portrait of Julie Manet Holding a Book, 1889

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet with a Budgie, 1890

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet with a Budgie, 1890

As you can see, in all the paintings from the “Julie series”, Julie is presented in an individualised way, not like typical girl portraits of the time with golden tresses and clutching a doll, looking cheerful and naive, rather, Morisot painted her reading a book, playing an instrument, daydreaming, lost in her thoughts, or sitting next to her pets, the budgie and the greyhound. Morisot wanted more for Julie that the role of a mother and a wife which was the typical Victorian ideal of womanhood, because as a prolific artist with a successful career, Morisot had also chosen an alternative path in life. There’s a distinct dreaminess and slight sadness about Julie’s face in most of these portraits, which only becomes emphasised as she grows older.

Now the “Julie grows up” element comes to the spotlight. We’ve seen Julie as a baby with honey-coloured hair, we’ve seen her with her pets, playing violin or listening to her cousin playing piano, but Julie is growing up so quickly… almost too quick to capture with a brush and some paint! My absolute favourite portrait of Julie is one from 1894, Julie Daydreaming, which reveals her inner life and her dreamy disposition the best. I love her white dress, her gaze, the shape of her hands, I love how every lock of hair is shaped by a single brushstroke. There’s a hint of sensuality in it as well, and it has drawn comparisons to Munch’s “sexual Madonnas”, which seems unusual at first since it was painted by her mother. I don’t really see it that way though, I see it simply as a portrait of a wistful girl in white wrapped in the sweetness of her daydreams.

I can’t help but wonder what she is daydreaming about. Tell me Julie, whisper it in my ear, I won’t tell a soul; is there a boy you fancy, would you like to walk through the meadows full of poppies, or watch the dew as it catches on the soft petals on roses in some garden far away, do you dream of damsels and troubadours, would you like to fly on Aladdin’s magical carpet, or listen to the sea in Brittany, what fills your soul with sadness Julie? And please, do tell me where you bought that dress – I want the same one!

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laerte, 1893

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laerte, 1893

Berthe Morisot, Julie Playing a Violin, 1893

Berthe Morisot, Julie Playing a Violin, 1893

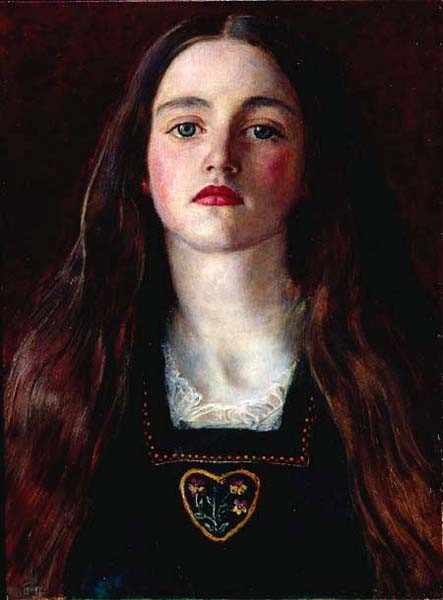

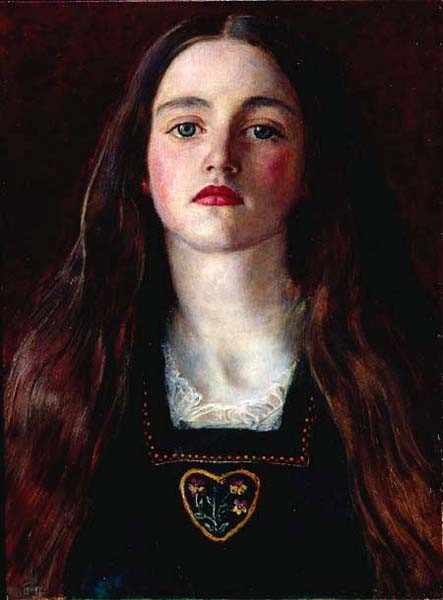

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Julie Manet, 1894

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Julie Manet, 1894

This portrait of Julie Manet by Renoir is particularly interesting to me; Julie is shown with masses of long auburn-brown hair, flushed cheeks, large elongated blue eyes with a sad gaze, in a sombre black dress against a grey background. The melancholic air of the portrait reminds me of one portrait from 1857 of Millais’ young little model and muse Sophy Gray; the same rosy cheeks, the same melancholic blue eyes and brown tresses.

John Everett Millais, Sophy Gray, 1857

John Everett Millais, Sophy Gray, 1857

And now Julie is a woman! In May 1900 a double wedding ceremony was held; Julie married Ernest Rouart and her cousin Jeannie Gobillard married Paul Válery. Her teenage diary, which she began writing in August 1893, is published under the name “Growing Up with Impressionists”. What started as just a bunch of notes, impressions and scribbles turned out to be a book in its own right, one which shows the art world and fin de siecle society through the eyes of a teenage girl. Julie died on Bastille Day, 14th July, in 1966.

Photo of Julie Manet, 1894

Photo of Julie Manet, 1894

She looks so frail and sad in the photo, but I can’t help but admire her lovely dress and hat. Sad little Julie, you just keep on daydreaming….

Tags: 1880s, 1894, 19th century, art, artistic upbringing, Berthe Morisot, daughter, daydreaming, Death, Edouard Manet, Eugene Manet, female artist, French Art, growing up, Impressionism, Julie Manet, Melancholy, model, mother, Muse, Painting, Paris, pastel, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, playing violin, Portraits, sad, Sophy Gray, white gown, wistful gaze

Gerda Wegener, The Bridal Recessional or The Little Bride (La petite mariée), 1927

Gerda Wegener, The Bridal Recessional or The Little Bride (La petite mariée), 1927