These four canvases by Botticelli hide a strangely dark and cruel tale inspired by a story from Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Nastagio Degli Onesti, Part one: Nastagio meets the woman and the knight in the pine forest of Ravenna, 1483, tempera on wood

Tormented by unrequited love, a young nobleman by the name of Nastagio Degli Onesti flees his hometown of Ravenna searching for some faraway place where he wouldn’t be thinking and dreaming of her – the beautiful haughty damsel who rejects him so cruelly over and over again. She enjoys rejecting him and seeing him suffer, and he tried suicide on a few occasions but all the attempts were all unsuccessful. Nastagio is tired from the unending blows of rejection and not even wanderlust can stir his dead, tired, lovelorn soul and his travel stops in a little place called Chiassi, a seaport a few miles away from Ravenna. It was the beginning of May and evening was approaching when Nastagio wandered into the dark mystic pine woods: “It chanced one day, he being come thus well nigh to the beginning of May and the weather being very fair, that, having entered into thought of his cruel mistress, he bade all his servants leave him to himself, so he might muse more at his leisure, and wandered on, step by step, lost in melancholy thought, till he came [unwillingly] into the pine-wood. The fifth hour of the day was well nigh past and he had gone a good half mile into the wood, remembering him neither of eating nor of aught else…” (*)

The distance, the change of scenery, nought could stop him from thinking of his cruel-hearted damsel in Ravenna; instead of beauties of nature, he only sees her pretty countenance, instead of the scent of the fragrant pine trees, he only breathes in her name from afar and breathes out desperation and longing. Ahhh…. Deep in mournful reveries that tear his heart even further, Nastagio “heard a terrible great wailing and loud cries uttered by a woman; whereupon, his dulcet meditation being broken, he raised his head to see what was to do and marvelled to find himself among the pines; then, looking before him, he saw a very fair damsel come running, naked through a thicket all thronged with underwood and briers, towards the place where he was, weeping and crying sore for mercy and all dishevelled and torn by the bushes and the brambles. At her heels ran two huge and fierce mastiffs, which followed hard upon her and ofttimes bit her cruelly, whenas they overtook her; and after them he saw come riding upon a black courser a knight arrayed in sad-coloured armour, with a very wrathful aspect and a tuck in his hand, threatening her with death in foul and fearsome words.” This is the scene from Boccaccio’s “Decameron” (fifth day, eighth story) which Botticelli has depicted in the first panel of the four-part series. I love the different phases of narration depicted in a single painting; in the background on the left we see Nastagio’s servants and then the tent, then we see Nastagio walking alone in the woods, and then right in the centre is the horrid encounter between Nastagio and the poor naked damsel. Having no sword or other weapon in hand, Nastagio picked up a branch, trying to defend the lady.

Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Nastagio Degli Onesti, Part two: Killing the Woman, 1483, tempera on wood

And now, in the background of the second panel, we again see the scene that had happened but minutes before; the woman being chased by an evil knight on a white horse. Now, the woman is killed and her body lies on the grass and the knight, angry faced but also seemingly accustomed to the actions, is tearing her flesh and ripping her organs out. Nastagio looks away in horror and the gesture of his arms shows how horrified and disgusted and bewildered he is by the strange scene that awoke him from his meditative reverie. Boccaccio writes: “This sight filled Nastagio’s mind at once with terror and amazement“. Dogs are eating her organs and now, on a moist grass of a dark pine forest, lies the naked dead body of a beautiful woman whose last breaths and words he had witnessed, and yet he was unable to save her from “anguish and death.” You would think that Renaissance was all about harmony and elevated themes, or so we were taught in grammar school, but what Botticelli has depicted here is a wild, untamed flow of savagery, the Dionysian element trying to stir the perfect Apollonian world of Renaissance; world of knowledge and reason is now tainted with blood, screams and torture.

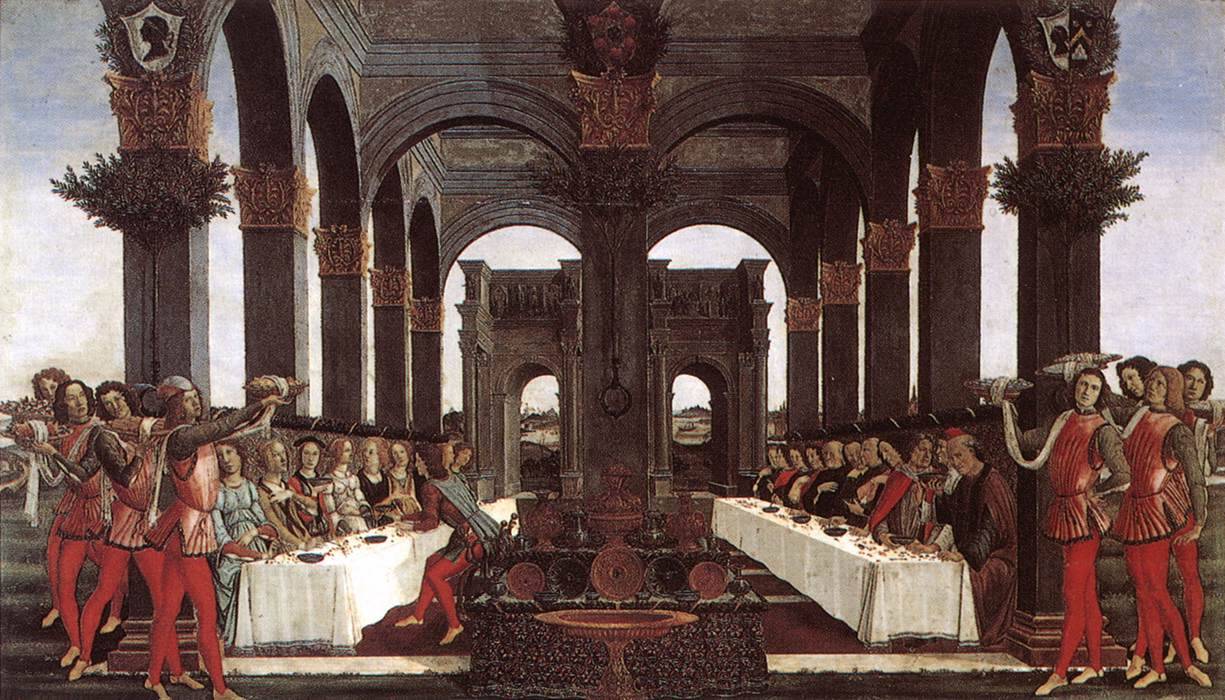

Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Nastagio Degli Onesti, Part three: The banquet in the forest, 1483, tempera on wood

The knight then explains to Nastagio the strange, barbarous scene that Nastagio had witnessed. Once upon a time, in days when Nastagio was but a child, the knight, whose name is Guido degli Anastagi, also lived in Ravenna and was also suffering from unrequited love. He loved a damsel who was as cruel and haughty as Nastagio’s beloved is, and who also enjoyed tormenting him, enjoyed to see him suffer from rejection. Unable to take it anymore, death seemed dearer to Guido then such a miserable, lovelorn existence, and he took his life. The damsel was pleased that such was the power of her beauty and charm, and she shed not a tear, but very soon she fell ill and died. Having no remorse before her death for her cruel behavior towards Guido, she was condemned to eternity in hell. Guido is also there, having committed the sin of suicide. And their punishment is intertwined; every Friday he has to chase her through the forest with the dogs, kill her and rip out her heart and feed it to the dogs. A cruel, cold, little heart which was incapable of love; that is her sin.

This repetitive punishment occurs every Friday and will repeat every Friday for as many years as there were months that the lady rejected Guido. Fascinated by this discovery, the following Friday Nastagio invites his family and friends for a little gathering, a party, and the cruel damsel whom he loves is also there. This is the third scene. Party is disturbed by the same savage ceremony of damned lovers and all the guests see the lady die again and her heart being ripped out. The Knight Guido again tells the crowd of their punishment in hell and it makes an impact on people, especially the females who teary eyed suddenly feel more loving and gentle. Nastagio’s beloved, the daughter of Paolo Traversiari, suddenly feels guilt and regret for her past actions and decides to marry Nastagio, fearing the same destiny might await her in case her cruel rejection of his love perseveres.

Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Nastagio Degli Onesti, Part four: Marriage of Nastagio degli Onesti, 1483, tempera on wood

The fourth panel, perhaps the dullest one, shows Nastagio’s wedding to the once haughty pretty wealthy maiden. Well, she is still pretty and wealthy, but more down to earth and perhaps more afraid of hell’s flames. She sends her maid to tell Nastagio that “she was ready to do all that should be his pleasure“. The scenery and its connection to the story is fascinating; in first two panels the setting is the wild, dark, mysterious pine forest where Nastagio wanders into because he is daydreaming and not paying attention to where he is going, so he walks into the woods as in a dream. The third panel is half-half; woods are still present in the background behind a long white-clothed dinner table. And then, after the moment of cruelty – the killing – is over, the setting goes to a more classical, polite, rational space; a banquet celebrating the marriage. Dense, repetitive row of trees gives a sense of depth and, along with the figure of the knight, and the emphasised narrative element of the painting, are all reminders of the Gothic art of the previous centuries, but it strangely fits the mood of the story.

Boccaccio’s tales from “Decameron” were suppose to carry a wise, education message to them and in this story the message is not to reject love because everyone deserves to be loved and have the right to love. Women should learn from the cruel damsel’s behavior and not follow in her footsteps. It is a sin not to love. Nastagio and his lady live happily ever after, but this isn’t the only positive outcome of the event, oh no, suddenly “all the ladies of Ravenna became so fearful by reason thereof, that ever after they were much more amenable than they had before been to the desires of the men.” Did no one found it strange that the only reason to return someone’s affection was the fear of suffering the same damnation? It’s interesting how some things sound so normal in these old tales, while they are utterly bizarre in our day and age.

The four pictures were commissioned in 1483 by Antonio Pucci, a wealthy merchant from Florence, for the occasion of the wedding of his son Giannozzo with Lucretia Bini. The theme was most likely chosen by Pucci himself and the paintings were intended for the bedroom of the newlyweds. Why, yes, a nude lady being killed by a knight and having her heart ripped out… quite a soothing, romantical scene to gaze at before bedtime and to see the first thing in the morning. An applause please, for Antonio Pucci’s wonderful aesthetic sense. The theme was chosen for its happy ending, I mean, they do get married in the end, but still. Now the paintings are, luckily, not gracing the walls of any poor couple’s bedroom, they are in Museo del Prado.