Elizabeth Siddal, beautiful and poetic working class girl, is perhaps best known for being the model for the famous Millais’ painting Ophelia painted in 1852, but it was Dante Gabriel Rossetti whose muse she was until her early death from a laudanum overdose.

‘ (…) All changes pass me like a dream,

I neither sing nor pray;

And thou art like the poisonous tree

That stole my life away.’ (Elizabeth Siddal)

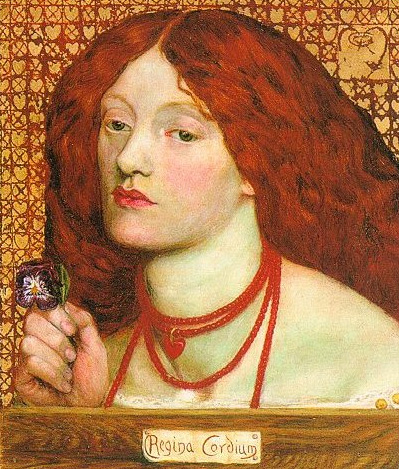

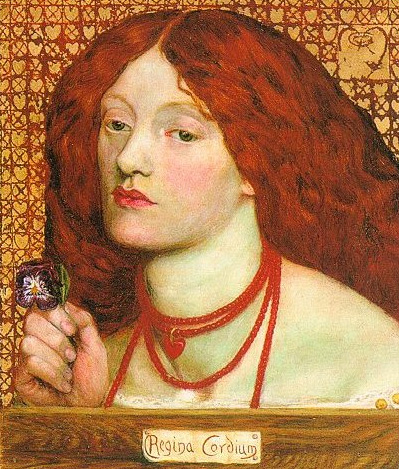

1860. Regina Cordium—Rossetti’s Marriage portrait of Siddal

1860. Regina Cordium—Rossetti’s Marriage portrait of Siddal

Elizabeth Siddal and Dante Gabriel Rossetti first met in 1849. when she was modelling for Deverell. By 1851. Elizabeth was modelling for Dante as well. In fact, he liked her so much as a model that he started painting her to the exclusion of all other models. They soon became engaged and Elizabeth started painting as well, thought her work was rather rough, harsh, compared to Rossetti’s. In 1855. John Ruskin, famous Victorian art critic, began to support her career and paid her £150 per year in exchange for all the drawings, sketches and paintings she produced. The themes of her paintings matched Pre-Raphaelite compositions; she painted idealized medieval scenes and illustrated Arthurian legends. It was during this period that she began to write poetry, her poems featuring dark themes about lost love, impossibility of finding true love and death. Art critic William Gaunt later commented ”Her verses were as simple and moving as ancient ballads; her drawings were as genuine in their medieval spirit as much more highly finished and competent works of Pre-Raphaelite art.”

In 1852. Dante and Elizabeth moved into Chatham Place and became extremely anti-social, spending their days enjoying each other’s love and expressing their affection for one another. The lovers coined affectionate nicknames, Dante calling Elizabeth his Dove. Rossetti was the one who taught her to paint and write, and he greatly admired her paintings, although they were mediocre, and even dubbed her a ‘creative genious’, blinded by his complete adoration for her. In turn, Elizabeth inspired him to write poetry. His period of great poetry production began when he met her and diminished when she died. His poem ‘A last confession’ shows his love for Elizabeth, even after her death, and in it he describes Elizabeth as having eyes “as of the sea and sky on a grey day.”

1864-70. Beata Beatrix

1864-70. Beata Beatrix

Previously mentioned art critic John Ruskin admonished Rossetti for not marrying the girl and giving her security. They did eventually get married, on 23rd May 1860. in a small seaside town of Hastings, after Elizabeth returned from her traveling to Nice and Paris due to her health problems. The only witnesses on the wedding were a few strangers whom they had asked in Hastings, no family or friends were invited. Elizabeth was so frail and ill at her wedding that she had to be carried to the church. Rossetti was reluctant to marry her and it wasn’t a secret that he had other women; Elizabeth was affected by the stress from the incidents and she used her frequent and serious illness to blackmail him. Due to her severe depression she had access to laudanum to which she became addicted to. In 1861. she became pregnant and the experience overjoyed her, but not long had passed and the tears replaced the laughter as she suffered a miscarriage. This left her with a post-partum depression from which she had never recovered. In the early months of 1862. she overdosed on laudanum and died in the evening of the 11th February 1862, aged only thirty two. Although her death was ruled as an accident, it is possible that she had committed a suicide.

Two years after her death Rossetti began painting his famous Beata Beatrix. The painting depicts Dante Alighieri’s Beatrice at the moment of her death, and Rossetti modeled Beatrice on his lost love Elizabeth whom he had not forgotten. The symbolism of the painting is peculiar; a red dove, a messenger of love, relates back to Rossetti’s love for Lizzie and the white poppy in her lap represents laudanum which was the cause of her death. In his letter to a friend Rossetti said he intended the painting “not as a representation of the incident of the death of Beatrice, but as an ideal of the subject, symbolized by a trance or sudden spiritual transfiguration.”

1860. Photograph of Elizabeth Siddal only two year prior to her death

1860. Photograph of Elizabeth Siddal only two year prior to her death

Overcome with grief, Rossetti had a journal with his unpublished poems buried with Elizabeth. He allegedly slit the book into Siddal’s red hair. By 1869, he was addicted to alcohol and drugs, and, after convincing himself he was going blind and he couldn’t paint, he started writing poetry again but he getting more and more obsessed over the poems he had buried with his wife. At Rossetti’s wish, the coffin was exhumed at night to avoid attention and curiosity from the public, and the Rossetti was not present. His agent Charles Augustus Howell who witnessed the exhumation reported that the corpse was remarkably well preserved (probably a result of laudanum) and that the coffin was full of Lizzie’s flowing coppery hair, which was said to have continued growing even after her death. Rossetti published the old poems but the exhumation tormented him for the rest of his life.

Rossetti wrote a poem ‘Without her’ and it’s his reflection on life once love has departed.

”What of her glass without her? The blank grey

There where the pool is blind of the moon’s face.

Her dress without her? The tossed empty space

Of cloud-rack whence the moon has passed away.

Her paths without her? Day’s appointed sway

Usurped by desolate night. Her pillowed place

Without her? Tears, ah me! For love’s good grace,

And cold forgetfulness of night or day.

What of the heart without her? Nay, poor heart,

Of thee what word remains ere speech be still?

A wayfarer by barren ways and chill,

Steep ways and weary, without her thou art,

Where the long cloud, the long wood’s counterpart,

Sheds doubled up darkness up the labouring hill.”

Tags: art, Christina Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Elizabeth Siddal, Poetry, Pre-Raphaelites

John Everett Millais, Spring (Apple Blossoms), 1859

John Everett Millais, Spring (Apple Blossoms), 1859