“Anne was devoured by secret regret that she had not been born in Camelot. Those days, she said, were so much more romantic than the present.”

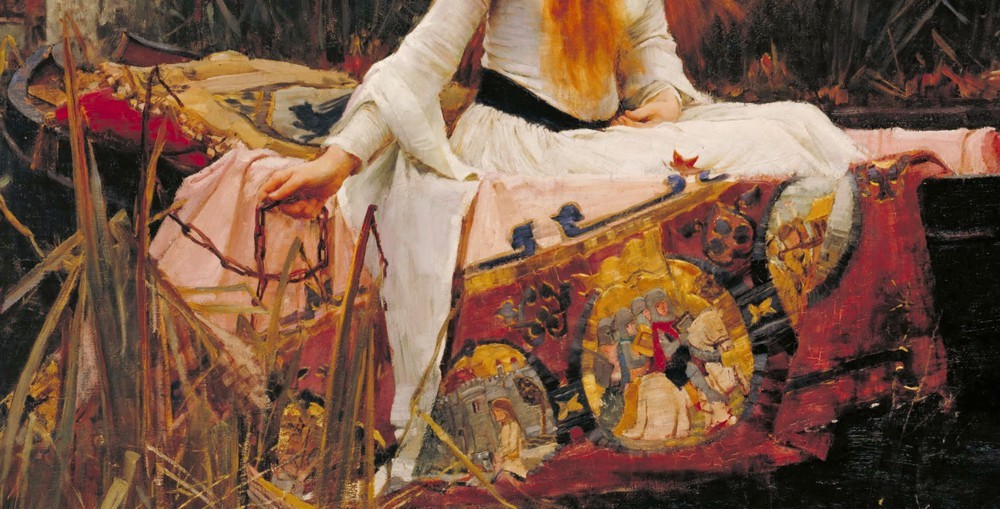

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888

What connects Elaine, The Lady of Shalott; a beautiful and doomed heroine of Arthurian legends and Lord Tennyson’s poem of the same name published in 1832, and Anne Shirley Cuthbert; a freckled, red-haired eleven year old orphan girl from Lucy Maud Montgomery’s well-know and well-loved children’s novel Anne of Green Gables? Elaine lived in the dark and magical Medieval times, in a tower, weaving her embroidery and gazing at the world through a mirror, and Anne lives on a beautiful Prince Edward Island in the late nineteenth century. Elaine suffered a romantical death from a curse that fell upon her, and Anne would give everything for such a tragical, romantical fate. “An Unfortunate Lily Maid”, chapter twenty-eight of Anne of Green Gables, holds answers to our questions. The thing that connects Anne with Elaine is the same thing that connects me and Elaine, me and The Smiths, Modigliani, Manics etc: fascination and adoration.

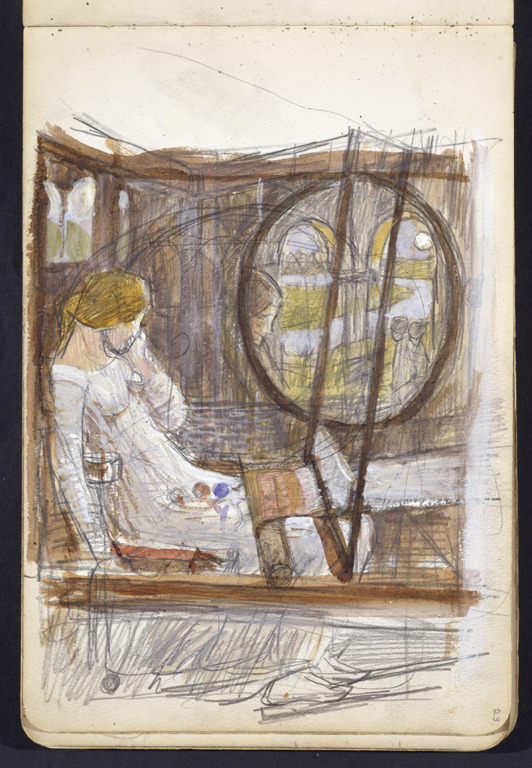

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, Sketch, Pencil, watercolour and bodycolour

Anne is a very dreamy, romantic, and imaginative girl who spends a lot of time fantasising and daydreaming about some other times and places, dreamier than her reality, even though, ironically, whilst reading the novel the reader will likely daydream about her time and place as more dreamy and romantical than our present. It is very easy to see what a heroine such as Elaine would appeal to Anne’s vivid imagination and romantic inclinations. If fate wasn’t as kind as to make Anne a princess from some fairy tale or a maiden from some Medieval romance, then acting is the second bets alternative and that is what Anne does in chapter twenty-eight. Along with her friends Diana, Ruby and Jane, Anne decides to lie in a boat, holding an iris flower instead of a lily, and float down the river “for ever and ever….” as Syd Barrett sings beautifully in the song “See Emily Play”. But of course, as it goes in Anne’s life, something goes wrong and a very dreamy situation becomes comical. Here is the passage from the book:

“Of course you must be Elaine, Anne,” said Diana. “I could never have the courage to float down there.”

“Nor I,” said Ruby Gillis, with a shiver. “I don’t mind floating down when there’s two or three of us in the flat and we can sit up. It’s fun then. But to lie down and pretend I was dead—I just couldn’t. I’d die really of fright.”

“Of course it would be romantic,” conceded Jane Andrews, “but I know I couldn’t keep still. I’d be popping up every minute or so to see where I was and if I wasn’t drifting too far out. And you know, Anne, that would spoil the effect.”

Walter Crane, The Lady of Shalott, 1864

It is almost amusing how Anne thinks it is ridiculous for a redhead girl to play Elaine because Lord Tennyson had described Elaine’s locks are golden. The most beautiful portrayal of the Lady of Shalott is the one painted in 1888 by John William Waterhouse and she is painted with masses of beautiful coppery red hair, clearly a legacy of the Pre-Raphaelites who had a penchant for red hair. It goes to show how life imitates art, for as soon as something is glamorised in art, it becomes fashionable in life as well. This was just a little digression. Here is how the passage continued:

“But it’s so ridiculous to have a redheaded Elaine,” mourned Anne. “I’m not afraid to float down and I’d love to be Elaine. But it’s ridiculous just the same. Ruby ought to be Elaine because she is so fair and has such lovely long golden hair—Elaine had ‘all her bright hair streaming down,’ you know. And Elaine was the lily maid. Now, a red-haired person cannot be a lily maid.”

“Your complexion is just as fair as Ruby’s,” said Diana earnestly, “and your hair is ever so much darker than it used to be before you cut it.”

“Oh, do you really think so?” exclaimed Anne, flushing sensitively with delight. “I’ve sometimes thought it was myself—but I never dared to ask anyone for fear she would tell me it wasn’t. Do you think it could be called auburn now, Diana?”

“Yes, and I think it is real pretty,” said Diana, looking admiringly at the short, silky curls that clustered over Anne’s head and were held in place by a very jaunty black velvet ribbon and bow.

They were standing on the bank of the pond, below Orchard Slope, where a little headland fringed with birches ran out from the bank; at its tip was a small wooden platform built out into the water for the convenience of fishermen and duck hunters. (…)

It was Anne’s idea that they dramatize Elaine. They had studied Tennyson’s poem in school the preceding winter, the Superintendent of Education having prescribed it in the English course for the Prince Edward Island schools. They had analyzed and parsed it and torn it to pieces in general until it was a wonder there was any meaning at all left in it for them, but at least the fair lily maid and Lancelot and Guinevere and King Arthur had become very real people to them, and Anne was devoured by secret regret that she had not been born in Camelot. Those days, she said, were so much more romantic than the present. Anne’s plan was hailed with enthusiasm. The girls had discovered that if the flat were pushed off from the landing place it would drift down with the current under the bridge and finally strand itself on another headland lower down which ran out at a curve in the pond. They had often gone down like this and nothing could be more convenient for playing Elaine.

“Well, I’ll be Elaine,” said Anne, yielding reluctantly, for, although she would have been delighted to play the principal character, yet her artistic sense demanded fitness for it and this, she felt, her limitations made impossible.

“Ruby, you must be King Arthur and Jane will be Guinevere and Diana must be Lancelot. But first you must be the brothers and the father. We can’t have the old dumb servitor because there isn’t room for two in the flat when one is lying down. We must pall the barge all its length in blackest samite. That old black shawl of your mother’s will be just the thing, Diana.”

The black shawl having been procured, Anne spread it over the flat and then lay down on the bottom, with closed eyes and hands folded over her breast.

“Oh, she does look really dead,” whispered Ruby Gillis nervously, watching the still, white little face under the flickering shadows of the birches. “It makes me feel frightened, girls. Do you suppose it’s really right to act like this? Mrs. Lynde says that all play-acting is abominably wicked.”

“Ruby, you shouldn’t talk about Mrs. Lynde,” said Anne severely. “It spoils the effect because this is hundreds of years before Mrs. Lynde was born. Jane, you arrange this. It’s silly for Elaine to be talking when she’s dead.”

Jane rose to the occasion. Cloth of gold for coverlet there was none, but an old piano scarf of yellow Japanese crepe was an excellent substitute. A white lily was not obtainable just then, but the effect of a tall blue iris placed in one of Anne’s folded hands was all that could be desired. “Now, she’s all ready,” said Jane. “We must kiss her quiet brows and, Diana, you say, ‘Sister, farewell forever,’ and Ruby, you say, ‘Farewell, sweet sister,’ both of you as sorrowfully as you possibly can. Anne, for goodness sake smile a little. You know Elaine ‘lay as though she smiled.’ That’s better. Now push the flat off.”

(….) For a few minutes Anne, drifting slowly down, enjoyed the romance of her situation to the full. Then something happened not at all romantic. The flat began to leak.“