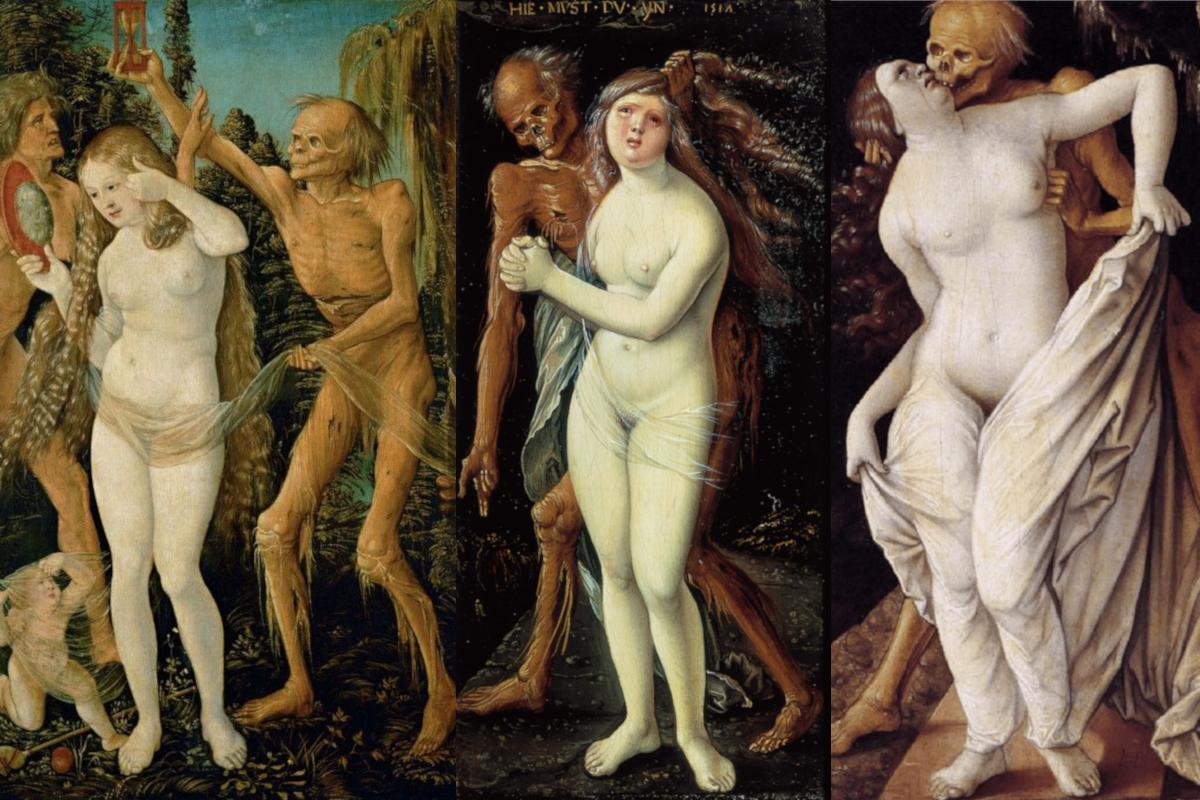

Edgar Allan Poe died on this day in 1849. Oh, it was a sad Sunday in Baltimore! The moss on the graveyard’s oldest tombstones sighed with lament and even the ravens cried! Poe is one of my favourite writers and these days I was intensely immersed in his poems and short-stories, particularly those which deal with his favourite topic: death of a beautiful young woman. I have an obsessive interest in Poe’s feminine ideal and two poems that I am sharing here today, “Annabel Lee”(published posthumously near the end 1849) and “Eulalie” (originally published in July 1845) feature a type of heroine which Poe loved. Poem “Eulalie” deals with the narrator’s past sadness and rediscovery of joy; both in love itself and in his object of love and that is a beautiful yellow-haired beloved whose eyes are brighter than the stars. Poe’s poems and short stories feature two very different types of female characters; first is the learned type, intellectually and sexually dominant, dark-haired, slightly exotic and mysterious woman such as Ligeia and Morella, who are in minority.

And then there’s the second type; Poe’s idealised maiden whose only purpose is to be beautiful, love the narrator and die… Poe’s ideal beloved is a beautiful tamed creature; young, often light haired with sparkling eyes and lily white skin, cheeks rosy from consumptive fever which will eventually bring her doom, passive, frail and vulnerable, romantically submissive girl who, just as in the poem “Annabel Lee”: “lived with no other thought/ Than to love and be loved by me.” A very young girl is more easily shaped to be what the narrator desires, and greater is the chance of her being a perfect companion; she can be subsumed into another’s ego and has no need to tell her own tale. (*) The maiden’s love has the power to transform the narrator’s miserable, doomed life, as is the case with the blushing and smiling bride Eulalie, but her death can be of an equal if not greater importance. Such is the fate of the characters such as Annabel Lee, Morella, Eleanora and Madeline Usher. In death, their singular beauty is eternally preserved. Death fuels the narrator’s art and is a starting point to contemplation.

I will devote a moment today to Poe’s poetry and maybe even reread some of my favourite stories. I feel that it’s just nice to remember birthdays of your favourite artists and poets, it gives more meaning to my otherwise meaningless existence.

Alex Benetel, “Chronicles at sea” ft. Madeline Masarik

Alex Benetel, “Chronicles at sea” ft. Madeline Masarik

Annabel Lee

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea,

But we loved with a love that was more than love—

I and my Annabel Lee—

With a love that the wingèd seraphs of Heaven

Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her highborn kinsmen came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in Heaven,

Went envying her and me—

Yes!—that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud by night,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we—

And neither the angels in Heaven above

Nor the demons down under the sea

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea—

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

Eulalie

I dwelt alone

In a world of moan,

And my soul was a stagnant tide,

Till the fair and gentle Eulalie became my blushing bride—

Till the yellow-haired young Eulalie became my smiling bride.

Ah, less, less bright

The stars of the night

Than the eyes of the radiant girl!

And never a flake

That the vapor can make

With the moon-tints of purple and pearl,

Can vie with the modest Eulalie’s most unregarded curl—

Can compare with the bright-eyed Eulalie’s most humble and careless curl.

Now Doubt—now Pain

Come never again,

For her soul gives me sigh for sigh,

And all day long

Shines, bright and strong,

Astarté within the sky,

While ever to her dear Eulalie upturns her matron eye—

While ever to her young Eulalie upturns her violet eye.

Poe, The original manuscript, 1845

*”Poe’s Feminine Ideal”, from Cambridge Companion to Poe