When David Bowie and Iggy Pop came to Berlin in the late seventies, they were welcomed by a divided city, a city which flourished in its confinement, breathing and living in hustle of capitalism, at the same time suffocating in an alienation which was its own product.

With Bowie’s arrival in Berlin, a period of cultural and artistic thriving started both for him and the city itself, which gleefully relived the glamour and decadence of its Weimar days.

Products of this fruitful, avant-garde, quite radical, sleek and modern, Europeanised, bohemian-aristocratic period of Bowie’s career were three albums; Low (1977), Heroes (1977) and Lodger (1979), and The Idiot (1977) and Lust for Life (1977) for Iggy Pop respectively. Drawn in deeper and deeper in cocaine hell, fame and shallowness of Los Angeles, Bowie had wanted for some time a clean start, a departure from his old personas because things did took him ‘where the things are hollow’. Iggy Pop wasn’t in a good place as well. West Germany was a place to go. Bowie was drawn to Berlin; a city at the heart of the West-East ideological conflicts, with a rich yet drab cultural history.

Brigitte Helm on the set of the Metropolis (1927, Fritz Lang)

Brigitte Helm on the set of the Metropolis (1927, Fritz Lang)

Bowie spoke himself about the reasons behind his moving to Berlin: ‘Life in LA had left me with an overwhelming sense of foreboding. I had approached the brink of drug induced calamity one too many times and it was essential to take some kind of positive action. For many years Berlin had appealed to me as a sort of sanctuary-like situation. It was one of the few cities where I could move around in virtual anonymity. I was going broke; it was cheap to live. For some reason, Berliners just didn’t care. Well, not about an English rock singer anyway.‘ (Uncut magazine, 1999)

In order to understand Berlin as it was in the seventies, it is necessary to understand its history, especially its ‘golden era’ of the 1920s – the decadency and cultural richness of the era equals the ones in Bowie’s time in Berlin. Berlin underwent a lot of transformation and served as the background for many political events since it first became the capital of the German Reich in 1871; from the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II to the roaring twenties, with all the freedom and avant-garde that characterised the decade, then the rise of Hitler and the Nazis, World War II and the events after it, the beginning of the Cold War and the division itself, building of the infamous wall, heroin addicts at the Bahnhof Zoo, arrival of Western rock stars – Lou Reed, David Bowie and Iggy Pop, later Nick Cave, all the way to the fall of the Wall and today’s modern ‘clean’, commercial and capitalist face of Berlin. It’s a city that nurtured its own bleakness, greyness and almost aggressive modernity. It’s also a city that allowed Bowie his freedom and anonymity.

Kircher’s vibrant colours express the overwhelming bustle and frenzy of life in a big city, and the loneliness of an individual at the same time. A million people and not a single friend.

Kircher’s vibrant colours express the overwhelming bustle and frenzy of life in a big city, and the loneliness of an individual at the same time. A million people and not a single friend.

I especially felt this modernity and sense of alienation in places such as Potsdamer Platz, Bahnhof Zoo (can’t deny its legacy) and Alexanderplatz. I remember it well, last summer I was standing on Alexander Platz with greyness all around me and trams passing in different directions – I felt like I was in one of Kirchner’s paintings. I also enjoyed watching trains arriving to the Bahnhof Zoo, wondering about the boroughs they connect. Oh, I simply adore that urban Romanticism about Berlin!

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Berlin Street Scene, 1914: People crossing each other’s paths, walking directionless, waiting for tramways, chatting, gazing into distance, waiting for clients; careless, nervous, breathing an air of avant-garde.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Berlin Street Scene, 1914: People crossing each other’s paths, walking directionless, waiting for tramways, chatting, gazing into distance, waiting for clients; careless, nervous, breathing an air of avant-garde.

In 1871, Berlin had only 800,000 inhabitants, in 1929 it had more than four million. Unlike London or Paris, Berlin wasn’t dotted with museums, churches and palaces, but was rather more ‘grey and uniform looking’.

‘Old Berlin consisted of six different boroughs: Mitte, Friedrichshain, Prenzlauer Berg, Kreutzberg, Tiergarten and Wedding. In 1920, seven surrounding towns were incorporated:Charlottenburg, Spandau, Schöneberg, Wilmersdorf, Lichtenberg, Neuköln and Kopenick. ‘Greater Berlin’ was thus formed by artificially uniting the existing, established eastern sector with a new area of land. The resulting caesura remained visible and tangible, both in terms of the social structure of the city and the mentality of its inhabitants.’ (Berlin in the 20s, Rainer Metzger)

This is an interesting information because we know that both Marlene Dietrich and Blixa Bargeld were born in Schöneberg – the same part of Berlin that Bowie and Iggy lived in. Bowie also named his song: Neuköln. The point is, Berlin was different, a concrete jungle half-coated in avant-garde, half in junkies, misfits and eccentrics. Paris had a romantic flair, London had a certain quirkiness, but Berlin had the legacy of Expressionists and Anita Berber, and of course – Gropiusstadt.

Anita Berber, looking like one of Klimt’s muses and a Biba girl at the same time.

Anita Berber, looking like one of Klimt’s muses and a Biba girl at the same time.

What Berlin also possessed, both in the 1920s and in the 1970s, was a certain fragility, awareness of its own transience. In that decadent frenzy, anxiety and excitement, the city lived, breathed and sensed its own collapse, as the Einsturzende Neubauten would later sing. Carl Zuckmayer, a German writer who lived in 1920s Berlin, writes about this feeling: ‘The arts blossomed like a field awaiting the harvest. Hence the charm of the tragic genius that characterised the epoch and the works of many poets and artists cut off in their prime… I remember well how Max Reinhardt… once said: “What I love is this taste of transience on the tongue – every year might be the last year.” Rainer Metzger further adds: ‘Today it is clear just how accurate, vigilant and prophetic this awareness of its own fragility, prior to the events of 1933, turned out to be.‘ Berlin’s artistic and cultural life at the time was a landslide, its seeming excitement, energy and a need for fun and intoxication was simply a facade that hid the unrest that lay on the inside.

David Bowie, Child in Berlin, 1977

David Bowie, Child in Berlin, 1977

Berlin in the seventies still held many of these characteristics, except it didn’t just sense the catastrophe but lived in the middle of it. Now a wall divided the West and the East, and Bowie arrived just in time to sing of lovers standing by the wall and create a new sound that would soak up the atmosphere of the city like a sponge. A sense of transience still lingered though, as we all know, Bowie’s artistic periods and personas didn’t last long, and from the moment he came it was evident that he may be gone soon. How long would Berlin continue to inspire him? One, two albums? It turned out to be three. If I may say – some of the most beautiful out of all his entire oeuvre. Bowie later ‘called “Heroes”, and his three Berlin albums, his DNA.’ (*)

Bowie’s divine Berlin era started as early as in the summer of 1976, when he started working on The Idiot with Iggy Pop, although his previous album Station to Station hints at a change that was soon to come, especially the ten minutes long title track, Bowie said himself: As far as the music goes, Low and its siblings were a direct follow-on from the title track Station To Station. It’s often struck me that there will usually be one track on any given album of mine, which will be a fair indicator of the intent of the following album. (Uncut magazine, 1999)

Iggy Pop said in this interview that The Idiot was inspired by the idea of Berlin, not the city itself yet, although they knew it was their next destination. That is so interesting because many times in art there’s a situation that the artist painted his reveries of a certain place, idealised visions of it, and not the realistic place itself. That’s the power of imagination.

Seeking spiritual and physical purification, and turning his interest from America to Europe again, Bowie found a new wellspring of creativity, imagination and happiness. Seems like those years served him good; not only did he produce three magnificent albums, and turned Berlin into a Mecca for the world of rock music, but also – found himself. He no longer needed a mask to hide himself, but rather found a way to express himself and go on stage as David Bowie.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, The Farewell, 1925-26

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, The Farewell, 1925-26

David Bowie loved Expressionism, and often visited Die Brücke Museum in Berlin, which was opened just nine years prior to his arrival. I remember reading somewhere that he loved watching twenty hour long Expressionistic films while travelling by train. He explained his love for the art movement in one interview:

‘Since my teenage years I had obsessed on the angst ridden, emotional work of the expressionists, both artists and film makers, and Berlin had been their spiritual home. This was the nub of Die Brucke movement, Max Rheinhardt, Brecht and where Metropolis and Caligari had originated. It was an art form that mirrored life not by event but by mood. This was where I felt my work was going. My attention had been swung back to Europe with the release of Kraftwerk’s Autobahn in 1974. The preponderance of electronic instruments convinced me that this was an area that I had to investigate a little further.‘ (Uncut magazine, 1999)

Did Bowie have Kirchner’s painting The Farewell in mind when he wrote lyrics for Sound and Vision? Just look at that beautiful vibrant electric blue outline on Kirchner’s figures of a woman with turquoise skin and a man in a brown-reddish coat. It really pierces your vision, and it’s imbued with almost a spiritual energy, just that single line would make a painting outstanding.

“Blue, blue, electric blue

That’s the colour of my room

Where I will live

Blue, blue

Pale blinds drawn all day

Nothing to do, nothing to say

Blue, blue” (*)

Covers of Bowie’s album Heroes and Iggy Pop’s Idiot both have a similar theme, which draws direct influence from artists such as Erich Heckel, mentioned by Bowie in an interview as one of his favourites at the time, and also the photographs of Egon Schiele. Bowie and Pop’s interpretations of the older artworks possess the same modernity, chic avant-garde, almost robotic poses. The titles are interesting as well, Hero and Idiot, antonyms of a sort.

Musically, I’ve always been a fan of Bowie’s Berlin era. Even though I like Bowie’s earlier stuff as well, this period endlessly captivates me, not just because the songs are so peculiar, strange and beautiful, but also because of the cult of the city itself, and also because it’s Bowie’s most-honest, most-himself phase up to that point. Songs from Low, Heroes, Lodger, The Idiot and Lust for Life are anomalies in a world of rock music, created in a specific place at a specific time. Berlin was never the same again. Back then, it was strange, unexplored and politically unstable. Then came capitalism, and they’ve created a seemingly clean and safe, but slightly soulless environment, which is just what tourists want. They don’t want to feel the real thing, or see junkies or live art, they want to take a photo standing in front of Brandenburger Tor. I can’t help it wonder, would Bowie chose Berlin as his artistic destination knowing the city as it is today?

Musically, Bowie and Pop’s albums from their Berlin eras convey that specific atmosphere of Berlin at the time, and that grey, modern and grim appearance of the city. As if their music responded to the scenery around them. Listening to tracks such as V-Schneider or Sense of Doubt you can picture the massive monstrous building of Gropiusstadt, or U-Bahns and Strassenbahns arriving at a station, you can feel the November coldness and bare trees in Mitte, tall soulless buildings, escalators at Europa Centar, never ending traffic jams…

Erich Heckel, Roquairol, 1917

Erich Heckel, Roquairol, 1917

And now some lyrics. Iggy Pop and David Bowie co-wrote Sister Midnight:

“Calling Sister Midnight

You’ve got me reaching for the moon

Calling Sister Midnight

You’ve got me playing the fool

Calling Sister Midnight

Calling Sister Midnight

Can you hear me call

Can you hear me well

Can you hear me at all

Calling Sister Midnight

I’m an Idiot for you

Calling Sister Midnight

I’m a breakage inside.”

David Bowie’s song ‘What in a World’:

“You’re just a little girl with grey eyes

So deep in your room,

You never leave your room

Something deep inside of me

Yearning deep inside of me

Talking through the gloom

What in the world can you do

What in the world can you do

I’m in the mood for your love

For your love

For your love” (*)

Tags: 1970s, 1970s Berlin, 1977, Berlin, David Bowie, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Heroes, Iggy Pop, Kirchner, Lodger, Rock Music, Station to Station, The Idiot, Weimar Berlin

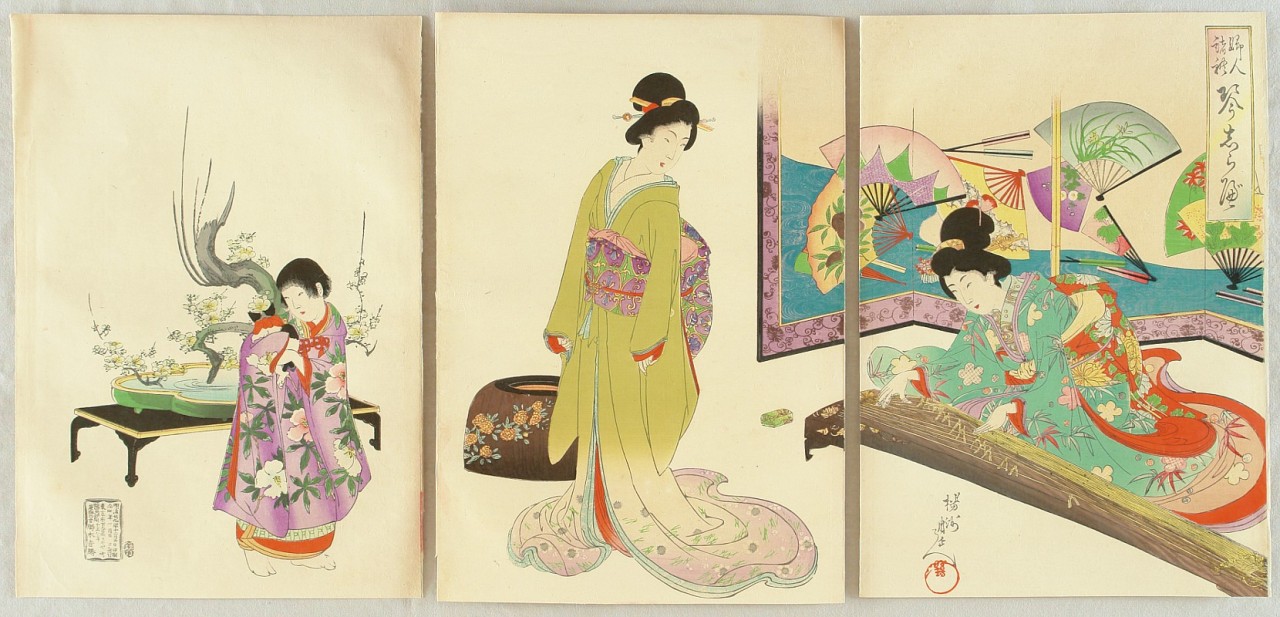

Chikanobu Toyohara (1838-1912), Koto Player – Azuma

Chikanobu Toyohara (1838-1912), Koto Player – Azuma